Betws-y-Coed - Overview

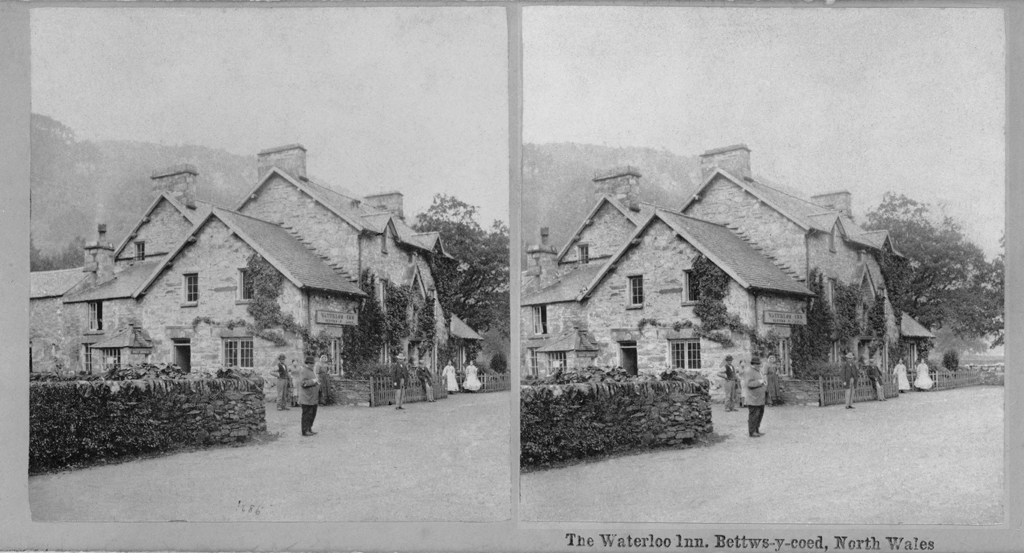

Betws-y-Coed originated around a small monastery during the sixth century and, until the rise of lead mining in the nineteenth century, was a small village with an agricultural economy. A former owner of Tŷ Mawr Wybrnant near Betws-y-Coed, William Morgan was the first to translate the complete Bible into Welsh in the 1580s. In 1815, as part of the London to Holyhead road project, Thomas Telford built the cast-iron Waterloo Bridge across the river Llugwy at the southern end of the village. The road bridge is constructed of a single span of cast iron ribs, the outer spandrels of which on each side carry the wording ‘THIS ARCH WAS CONSTRCUTED IN THE SAME YEAR THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO WAS FOUGHT’ and the national emblems of Wales, England, Ireland and Scotland.

This new road led to the village becoming a major coaching centre and a rapid development in tourism. In 1868 the road was supplemented by the arrival of the railway line from Llandudno, which led to a further development in the size of the town.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the village attracted a great number of landscape artists of international renown. In 1844, John Cox was the first British landscape artist to decamp at the Royal Oak Hotel. On one of his many later visits he even painted the signboard which is still on display today, but has been brought indoors for protection. The Norwegian painter Hans Frederik Gude lived here with his family for a few years during the 1860s and Onorato Carlandi from Italy returned time and again for some thirty years following his first visit in 1880.

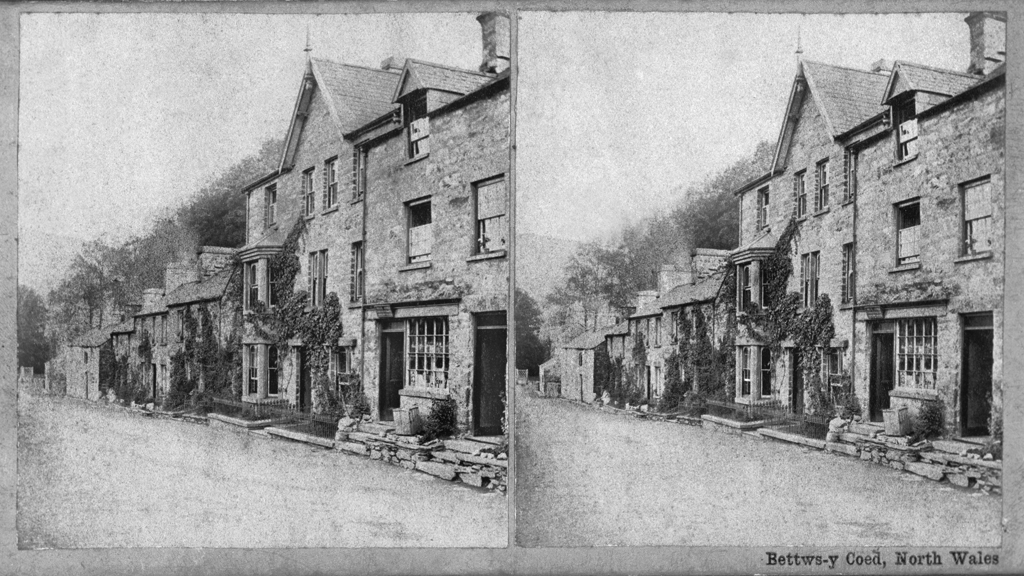

The architecture of the village retains much of its Victorian character. Today, Betws-y-Coed derives its main income from outdoor tourism thanks to the many forests, rivers and waterfalls dotted around the landscape.

Accounts of Travel

Ein Herbst in Wales, 1856

Julius Rodenberg (1831 – 1914)

Als ein Dämmerbild voll Frische und Waldkühle trat uns bald das Dörflein Betwys y Coed, das Brückendorf, entgegen. Es heißt so wegen einer Brücke, der s. g. Pont y Pair oder Kesselbrücke, die hier über den [Llygwy] führt. Der Brückenbogen von Pont y Pair, mit wildem Gewächs ganz behangen, umspannte mir eins der lieblichsten Bilder, die ich jemals gesehn. Über den Felsen, rings um mich, donnerten die Waßer; in einem Moosfelsen gelagert, und vom Waßer umstrudelt, sah ich drei jugendliche Frauengestalten, die Nixen dieses Stromes! Im Waßerspiegel glänzte das Gold der Abendröthe. Am Ufer durch Tannenstämme, die bis oben hinauf röthlich beleuchtet waren, glühte ein Feuer und überstrahlte das dämmergrüne Gebüsch. Eine reizende Waliserin saß auf der Gartenmauer hinter den Bäumen; Kinder in weißen Gewändern umspielten sie. Und zur andern Seite, aus einer Schmiede stieg blauer Dampf empor, glühende Funken flogen und knisterten darin und fielen zuletzt wie ein Goldregen über das dunkle Waßer nieder. Und alles Das auf einem grünen Waldhintergrunde und in duftiger Dämmrung. Es gieng mir wie ein glänzender Traum vorüber.

Like a dusky image full of brilliance and the freshness of the forest, Betws-y-Coed, the village of bridges, soon welcomed us. It is called that after a bridge, Pont-y-Pair or the Bridge of the Cauldron, passing over the river [Llugwy] at this spot. The arches of Pont-y-Pair Bridge, covered entirely by untamed greenery, framed one of the loveliest images I ever beheld. The water thundered over the rocks and all around me; situated on a mossy boulder enclosed by bubbling water, I witnessed the youthful shapes of three women, the naiads of this stream! The golden sunset glistened in the water mirror. A fire gleamed along the riverbank, breaking through the stems of the reddish glowing fir trees and outshining the dusk-green undergrowth. A comely Welsh woman sat on a garden wall behind the trees, children in white garments playing around her. On the opposite side, blue smoke rose from a smithy, glowing sparks flew and crackled and finally rained down over the dark water like a shower of gold. All this I saw in front of a green forest background and a fragrant dusk. It all passed by me like a radiant dream.

Hydrotechnische Bemerkungen gesammelt auf einer Reise durch England, Holland, Nord- und Süddeutschland im Jahre 1830, 1830

Georg Dittler (1797 – 1835)

Die Axe dieser [Waterloo] Brücke liegt rechtwinklicht über dem Stromstrich des Flusses, der hier besonders hohe Ufer hat. ...

Die beiden äussern Rippen sind besonders verziert und tragen in ihren 20 Zoll hohen Bogenkränzen ... eine künstlich durchbrochene Arbeit, welche in einer Zusammensetzung von Buchstaben besteht, deren englischer Text im Deutschen ungefähr also lautet: „diese Brücke wurde im demselben Jahre gegründet, als die Schlacht von Waterloo geschlagen ward.“

In den vier Gewölbswinkeln der zwei Stirnrippen finden wir in vollendeter Gussarbeit eine Rose, als Emblem von England, eine Distel, als solches von Schottland, das drelättrige Kleeblatt als Sinnbild von Irland und endlich den Lauchstengel, als jenes von Wallis, wobei die beiden letzern Bilder in der flussaufwärtsstehenden und die beiden erstern in der flussabwärtsstehenden Stirnrippe angebracht sind. Auch dieser Bau ist von dem Ingeneur Telford projectirt und ausgeführt worden. Im Jahr 1816 wurde er dem Publikum geöffnet. Ihre Breite misst 32 Fuss, sie hat erhöhte Fusswege und ein geschmackvoll verziertes Geländer.

The centre line of the [Waterloo] bridge lies perpendicular to the water stream of the river which has particularly high banks in this spot. ...

The two outer ribs have been decorated especially: the 20 inch-high arched girders display artful trellis work consisting of a set of letters that read, ‘This arch was constructed in the same year the battle of Waterloo was fought.’

The four spandrels contain the most accomplished cast ironwork in the shape of a rose, the emblem of England, a thistle, that of Scotland, the shamrock as symbol of Ireland, and finally the leek, the symbol of Wales, whereupon the latter two have been installed upstream and the former two are situated in the spandrels facing downstream. This work, too, was engineered and carried out by the engineer Telford. It was opened to the public in the year 1816. The width of the bridge measures 32 feet; it has a raised pavement on both sides and tastefully decorated parapet railings.

"Ein Sommerausflug nach Wales", c. 1860s

Wilhelm Heine (1827 – 1885)

Der Eintritt von Bettws-y-Coed wird auf malerische Weise durch eine Gruppe gothischer Häuser neben einer aus dem fünfzehnten Jahrhundert herrührenden Brücke, Pont-y-Pair, bezeichnet. Letztere, aus vier unregelmäßigen mit Epheu überwachsenen Bogen bestehend, unter denen ein munterer Wasserfall durchhüpft, ist das Werk des eingeborenen Maurers Howel. Weiter unten fließt der Llugwy ruhig, bis er sich eine halbe Meile weiter in den Conway ergießt. Dieser Ort ist ein Lieblingsaufenthalt englischer Landschaftsmaler, deren weiße Schirme man thalauf und thalab an verschiedenen Orten wahrnimmt. In den verschiedenen Thälern, die sich hier vereinigen, findet man die verschiedenartigsten Vorwürfe, idyllischer, pastoraler und romantischer Landschaft. Felsen aller möglichen Arten und Formen sind entweder nackt und in großen Formen zu finden, oder theilweise von reicher Vegetation bedeckt; knorrige, kräftige stolze Eichen, graziöse Buchen, düstere Kiefern und schlanke Tannen sind einzeln, in Gruppen oder Gehölzen über Thäler und Hänge verstreut und beide Flüsse enthalten eine große Anzahl von Stromschnellen und Fällen.

The entrance to Betws-y-Coed is notable for the picturesque setting of a group of houses situated by a fifteenth-century bridge, Pont-y-Pair. The latter, consisting of four ivy-covered, irregular arches above a sprightly waterfall, is the work of the local mason Howel. Further downstream, the Llugwy runs calmly until it flows into the river Conwy another half mile onwards. This spot is the favourite location of English landscape artists, whose white parasols can be spotted in different locations all around the valley. The diverse valleys that join up here, provide the most varied prospects of idyllic, pastoral and romantic landscapes. Crags of all shapes and types display themselves either bare and in grand style, or they are partially overgrown with rich vegetation. Gnarled, firm proud oaks, graceful beeches, sinister pines and slender firs clump together in woodland or are dotted singly around the valleys and along the slopes. Both rivers contain a great number of rapids and waterfalls.

"En Angleterre", c. 1880s

Marie-Anne de Bovet (1855 – 19??)

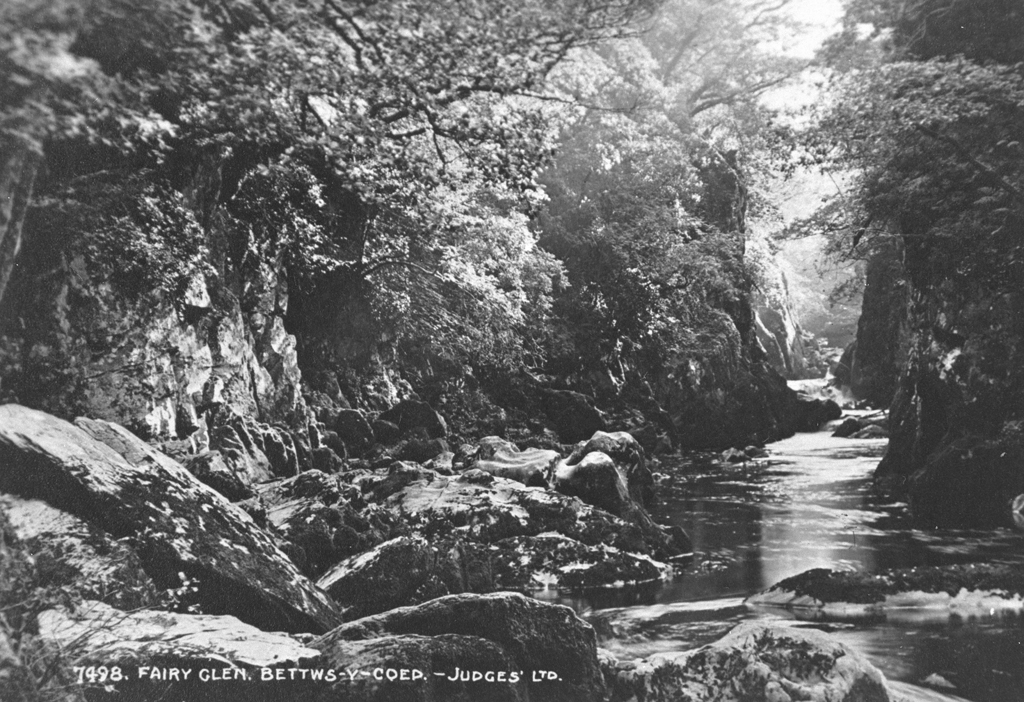

Dans la gorge des Fées, profonde et étroite crevasse creusée dans le roc vif par le Conway, qui y dégringole en tourbillons d’écume, les paysagistes envahissent le lit même du torrent, où, sans crainte des coryzas qui les guettent, ils piochent diligemment le même effet de lumière frisante sur l’eau, le feuillage et les rochers. Il s’y commet de lamentables crimes de lès-art! Mais le modèle console des copies, et, s’ils tiennent de la place, les touristes de cette espèce ont du moins le mérite de n’être pas bruyants.

In the Fairy Glen, a deep and narrow crevice carved in the active rock by the Conway, that tumbles down there in whirlpools of foam; the landscape painters invade the very bed of the torrent, where, without a care for the cold they might catch; they labour diligently to capture the same effect of the light on the water, the leaves and the rocks. Terrible crimes against art are committed here! But the model consoles the copies, and, if they take up space, at least this type of tourist has the merit of not being noisy.