Britannia Bridge - Overview

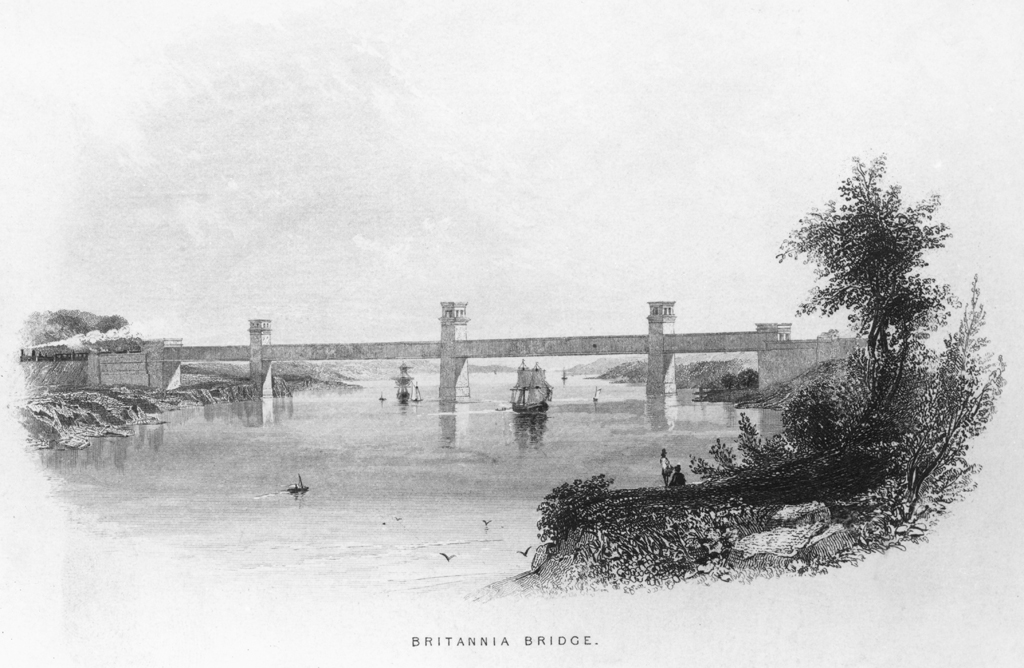

The Britannia Bridge was constructed by the civil engineer Robert Stephenson as a tubular railway bridge over the Menai Strait. The commissioning of the Britannia Bridge followed the opening of Thomas Telford’s Menai Suspension Bridge, which had revolutionised coach travel between Holyhead and London. With the steadily increasing number of travellers between Ireland and Wales however, the construction of a railway line across the strait became necessary. Work on the bridge started in 1846 and four years later it was opened to the public.

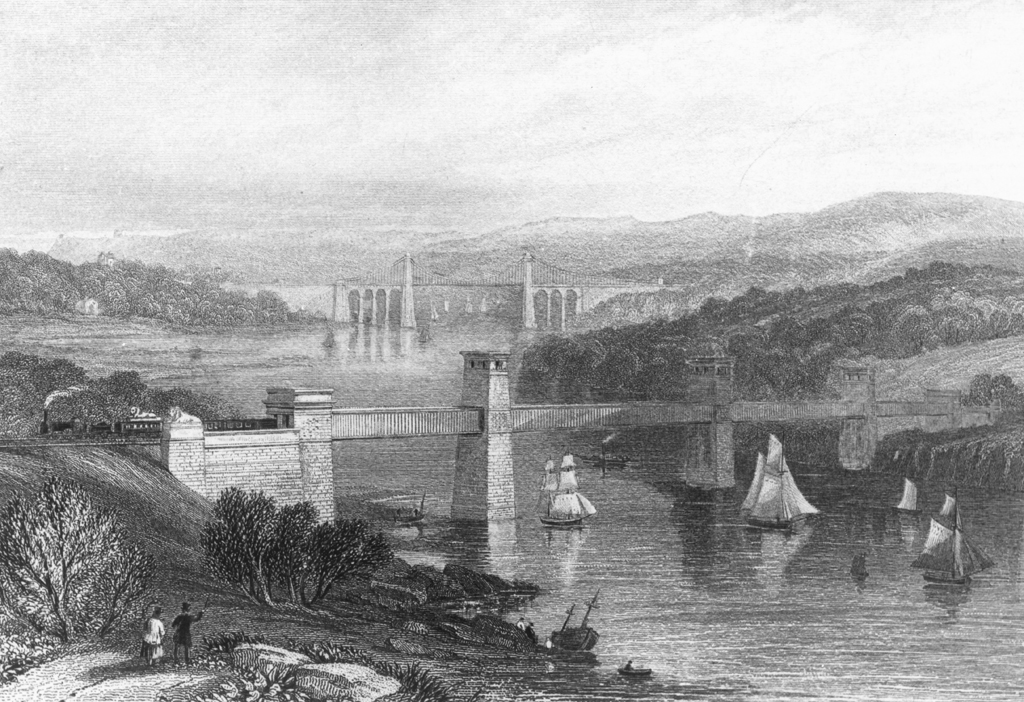

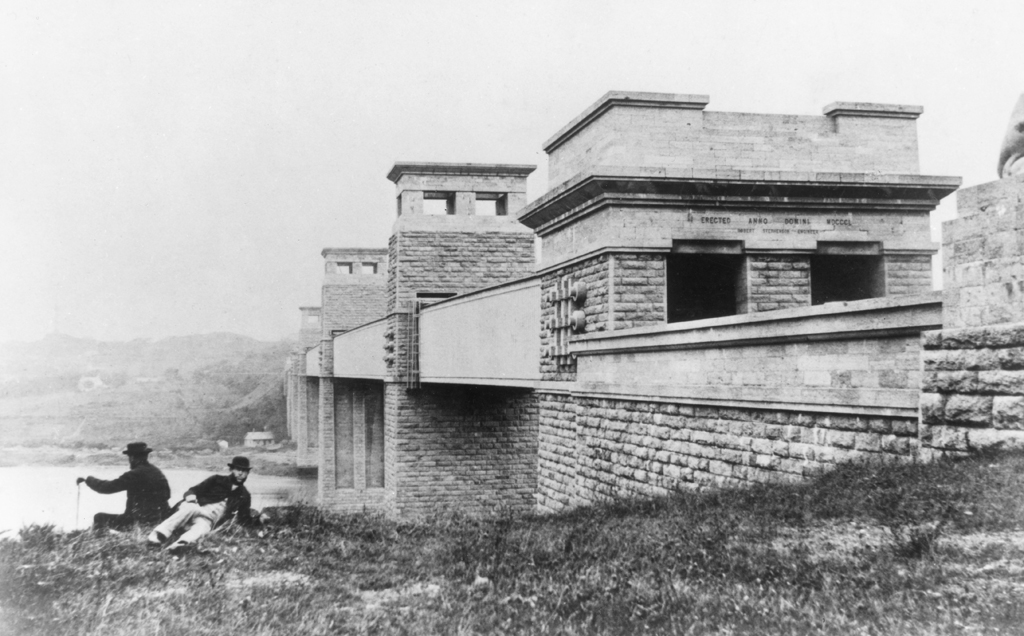

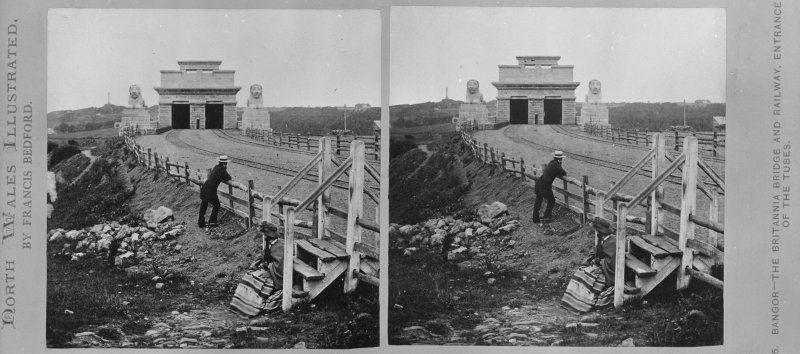

To complete a bridge of this span, supporting the weight of two railway tracks was a difficult prospect. Following the same conditions that had been put in place when Telford designed the Menai Suspension Bridge, Stephenson’s railway bridge also had to be high enough to allow ships to sail below it at all times. Stephenson came up with a revolutionary new tubular design that allowed a greater span without the need for suspension trains, testing this design with his construction of the smaller railway bridge across the estuary at Conwy, opened in 1849. The masonry of the Britannia Bridge uses ancient Egyptian designs and four enormous lions, also in Egyptian style, decorate the entrances to the bridge on both sides.

Like the Menai Suspension Bridge, countless tourists flocked to the Britannia Bridge throughout its construction and after it was opened. For a long period, visitors were even allowed to explore the inside of the tubes! One excited account by the German traveller Rudolph Delbrück relates how, during a particularly hot and dry summer, the wooden roof of the tubes had dried out and caught fire from the sparks of the passing train. In turn, the burning tubes set the luggage ablaze which was carried on top of the train.

Following a substantial fire in 1970, the tubular girders were removed as they were deemed to have become structurally instable due to the heat of the blaze. The bridge was reconstructed and now features two decks, the lower one still allowing trains to cross the Menai Strait, while the top carries the A55 road. The original masonry piers support the new structure and the stone lions are still in place.

Accounts of Travel

"Ein Sommerausflug nach Wales", c. 1860s

Wilhelm Heine (1827 – 1885)

Der berühmte Ingenieur Stephenson empfahl eine Ueberbrückung mittels gußeiserner Bogen von 450 Fuß Spannweite, allein die Admiralitätscommission bestand darauf, einen Raum von 100 Fuß Höhe nicht nur in der Mitte des Bogens, sondern auch dicht an den Pfeilern zu haben, und somit sah sich Stephenson genöthigt, seine erste Idee aufzugeben und projectirte nun einen Bau, einem einzigen gewaltigen Balken gleichend, dessen Stabilität von der Stärke seiner Theile abhängt, und der, an einer anderen Stelle zusammengesetzt, in total nach seinem Bestimmungsort geflößt und dort als Ganzes in seine Lage gehoben ward. Unterstützt von Herrn Fairbairn und Professor Hodgkinson machte Stephenson eine Reihe von Experimenten und so entstand diese Brücke, in der Form einer Röhre gleichend, deren Seiten aus anderen kleinen Röhren gebildet sind. Der Ausdruck Röhre soll jedoch hier nicht ein rundes Profil andeuten, denn das Hauptprofil der Brücke sowohl als die kleineren Balken sind rechtwinklich, jedoch sind alle Theile hohl und aus Eisenplatten zusammengesetzt. ...

Die erste dieser Röhren war am 4. Mai 1849 vollendet, am 20. Juni aufs Wasser gebracht und am 9. November in ihrer permanenten Lage. Die Eröffnung der ersten Linie fand am 18. März 1850 statt, die des ganzen Baues am 21. Oktober desselben Jahres und die Gesammtkosten des Baues betrugen 621,855 Pfund Sterling (4,145,684 Thaler) [ca. £72 Mio. oder €79,5 Mio. in 2017]. Aus der Ferne gesehen, läßt sich die wundervolle Construction dieses Bauwerks kaum ermessen. Der Anblick ist etwas zahm und uninteressant und gleicht ungeheuren Balken, welche auf den Pfeilern ruhen, während die in der Ferne sichtbare Hängebrücke einen ungleich mehr malerischen Eindruck macht. Betritt man aber den Schienenweg in den Röhren, prüft man Construction und Verhältnisse näher, so kann man sich der Bewunderung dieser kühnen Geister, die ein so gewaltiges Werk ersannen und so bedächtig und sicher ausführten, nicht erwehren.

The famous engineer Stephenson recommended the construction of a cast iron arched bridge with a span of 450 feet, but instead the Admiralty insisted on a minimum height of 100 feet in the centre of the arch as well as near the pillars. Thus, Stephenson felt himself obliged to surrender his first idea and planned a structure now resembling one enormous beam, whose stability depended on the strength of its parts. The beam, assembled in another location, was going to be floated to the final destination point and there winched into place in its entirety. With support from Mr Fairbairn and Professor Hodgkinson, Stephenson carried out a series of experiments and, thus, the present bridge was developed, resembling a tube whose sides consist of other small tubes. The term ‘tube’ is not intended here to describe a round profile, for the main profile of the bridge as well as the smaller beams are rectangular, but all parts are hollow and constructed of iron plates. ...

The first of these tubes was completed on 4 May 1849, was put on water on 20 June and installed into its permanent position on 9 November. The opening of the first track was on 18 March 1850 before the opening of the entire edifice on 21 October the same year. The total cost of construction was £621,855 (4,145,684 Thalers) [c. £72 mill or €79.5 mill in 2017]. Viewed from a distance, it is next to impossible to grasp the wonderful properties of this structure. Its appearance is somewhat tame and uninteresting and resembles enormous beams resting on pillars, whereas the suspension bridge visible in the far distance gives a disproportionately more picturesque impression. Stepping onto the railway inside the tubes, however, and inspecting the construction work and properties more closely, it is impossible to resist admiring the daring spirits who thought up this enormous work and carried it out so diligently and safely.

"Ein Ausflug nach Nordwales", c. 1860s

Wilhelm Heine (1827 – 1885)

Die Meerenge von Menai ist nicht so breit, als [der Rhein bei Mainz und die Donau bei Wien]; die Brücke ist nur von zwei Pfeilern im Wasser und zwei Pfeilern am Ufer getragen; die Röhren aber sind sehr prosaisch, zumal wenn man, wie ich kurz vor her, die drei Gitterbrücken über den Rhein bei Mainz, Coblenz und Köln gesehen. Der Meeresarm hatte ungefähr das Aussehen des Rheins bei Coblenz, überhaupt eines Flusses, weil man auf keiner Seite das Meer herschimmern sah. Der Jugendtraum war halb zu Wasser; allein daran war die Britannia-Brücke selbst unschuldig. Sie bleibt doch die Mutter der Gitterbrücken, ein Triumph der Mathematik! Im Augenblicke, wo der jüngere Stephenson den Satz als richtig erprobt hatte, daß eine Eisenröhre ebenso viel Tragkraft besitze, als ein massiver Eisencylinder vom gleichen Durchmesser oder um das Gewicht des Kernes noch mehr, war eine Wohlthat für den Weltverkehr gefunden, welche den Dampfschiffen und Eisenbahnen sich als drittes Wunderwerk anschließt. Gleich nach obigem Satze fand man, daß auch eine durchbrochene Röhre noch genügende Widerstandskraft behält, und die Gitterbrücken waren erfunden, die proteus-artig jedes Jahr in neuer Conftruction auftauchen und ohne welche der heutige Eisenbahnbau sich fast nicht mehr denken läßt, wenigstens unsere Ströme heute noch nicht überbrückt wären. Was hätten nicht die Römer um eine solche Erfindung gegeben! Wann wird die Welt wieder das Schauspiel eines solchen Sohnes, eines solchen Vaters sehen – Letzterer der Erfinder der Eisenbahnen, Ersterer der Vater der Gitterbrücken!

The Menai Strait is not as wide as [the Rhine near Mainz and the Danube near Vienna]; the bridge is only carried by two pillars in the water and two on the banks; yet, the tubes are very prosaic, especially if one, like myself, has previously seen the lattice bridges over the Rhine in Mainz, Koblenz or Cologne. The strait had roughly the appearance of the Rhine near Koblenz, and looked much like a river because it was impossible to see the ocean sparkle at either end. The childhood dream was all but over; yet, the Britannia Bridge itself was innocent. Despite everything, it remains the mother of all lattice bridges, a triumph of mathematics! The moment that the younger Stephenson had proved the theorem that an iron tube possesses as much bearing capacity as a solid iron cylinder of the same diameter and even more around the weight of the core, a blessing for world transport had been found, joining up with steam ships and railway trains as a third miracle. Similar to the above theorem, it was found that a perforated tube still retains enough of its strength and thus the lattice bridge had been invented. With their protean quality, lattice bridges appear in new shapes every year. Without them, today’s railway construction is next to unthinkable and our rivers today would have still not been bridged. What the Romans would have given for such an invention! When will the world see the likes of such a son and such a father – the latter the inventor of the railway train and the former the father of the lattice bridge!