Caernarfon - Overview

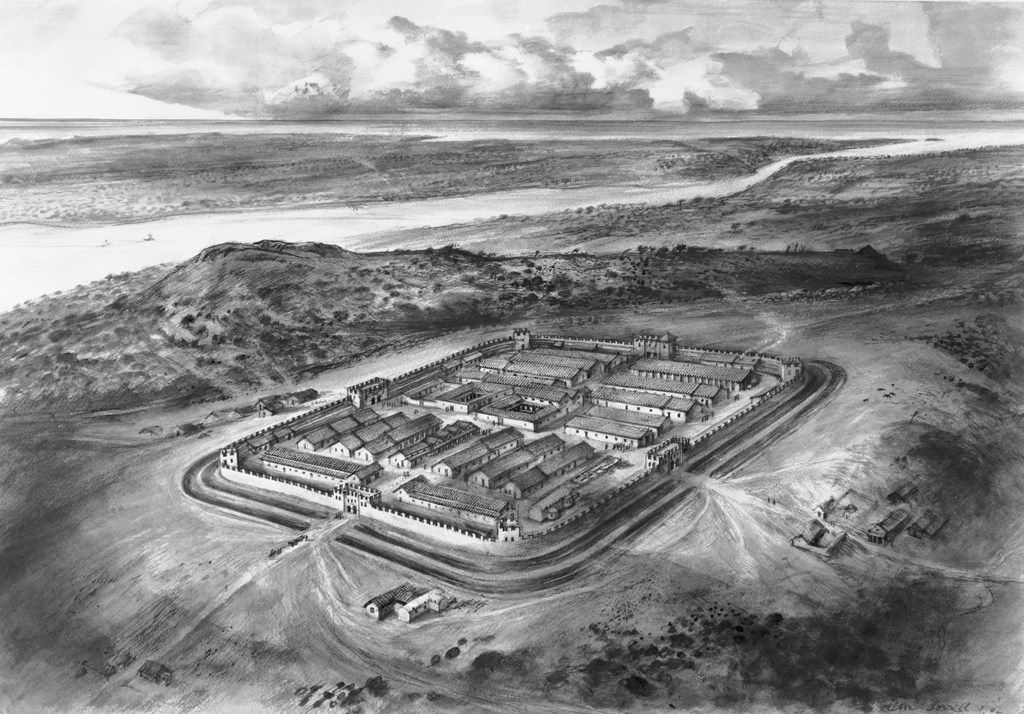

Facing Anglesey, Caernarfon is situated on the south-western half of the Menai Strait. The earliest occupation is found at the Roman fort of Segontium, which was built to subdue the rebelling Ordovices, the Celtic tribe living then in this region. Internationally, this large town is mostly known for its castle, built by the English king Edward I, who fortified the town and banned all Welsh people from living inside the town walls after the defeat of Llewelyn ap Gruffudd in 1282. In the twentieth century it was used for the investiture of two Princes of Wales, first in 1911 and latterly in 1969.

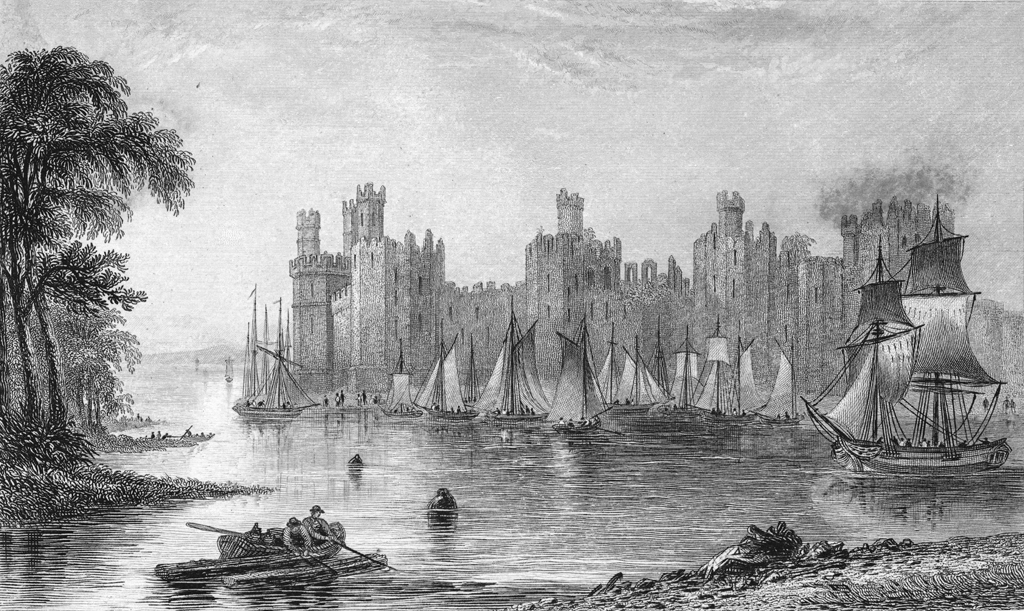

While the character of the town remained essentially rural during the nineteenth century, Caernarfon’s prime location in proximity to the slate quarries of north Wales contributed to the development of its harbour. From here, high-quality slates in all colours, shapes and sizes were shipped to the four corners of the world.

Many tourists came to Caernarfon either to explore the picturesque ruins of the Norman castle or take advantage of the town’s close proximity to Snowdonia. In 1828, Prince Herman von Pückler-Muskau engaged a local boy and his horse carriage for a journey to Llanberis, which they reached in only half an hour because the boy interpreted the Prince’s shouts of fear as encouragement to hurtle along the roads at an even faster pace. In 1862, the French journalist Alfred Erny experienced the locality at a more leisurely pace. He spent a few days exclusively in the town and produced a detailed account of his visit to the Eisteddfod held inside the castle. He was surprised, however, that in this most Welsh-speaking corner of the country, the majority of the public speeches were given in English.

Accounts of Travel

Reise durch England, Wales und Schottland im Jahre 1816, 1816

Samuel Heinrich Spiker (1786 – 1858)

Vom Castell gingen wir zur Stadt hinab. Ein Theil der gegen die See zu angelegten Vertheidigungswerke derselben, aus hohen Mauern mit halbrunden Thürmen, in abgemessenen Entfernungen, bestehend, befindet sich noch jetzt in einem sehr guten Zustande. Zwischen diesen und dem Meere ist ein schöner, wohlgeebneter Spaziergang angelegt, welcher mit der in England zur Natur gewordenen Nettigkeit gehalten, und bei schönem Wetter von den Bewohnern der Stadt fleißig besucht wird. Eine steinerne Brüstung, die hie und da von Eisengittern unterbrochen wird, läuft am Meere hin, und ein großer viereckter, weit aus der Mauer hervorspringender, Thurm, auf beiden Seiten, nach dem Spaziergange hin, durchbrochen, öffnet sich nach der Seeseite in ein großes Thor, und bildet einen Eingang in die Stadt. – Die Aussicht über den Hafen und das gegenüberliegende Anglesea ist trefflich.

Der Stadtmauer, am Meere hin, folgend, kamen wir zu einer kleinen Kapelle, aus welcher uns der Ton der Orgel und der Gesang mehrerer Kinder entgegenhalte. Angelockt von diesem wandten wir uns um die Ecke der Mauer zu einem zweiten Thore hinein, und sahen nun eine kleine, freundliche, im neueren gothischen Geschmacke gebaute Kirche vor uns. Wir gingen auf einige Augenblicke hinein, und fanden sie mit wohlgekleideten Leuten, beiderlei Geschlechts, angefüllt, die mit großer Andacht sangen und durch unser Eintreten wenig oder gar nicht gestört zu werden schienen. Auf dieser (der östlichen) Seite der Stadt sind die Schiffswerfte, auf denen wir mehrere kleine und zwei oder drei größere Schiffe von 150–200 Tonnen halb fertig fanden. – Einige von den Thürmen in der Mauer, auf dieser Seite, schienen bewohnt zu seyn.

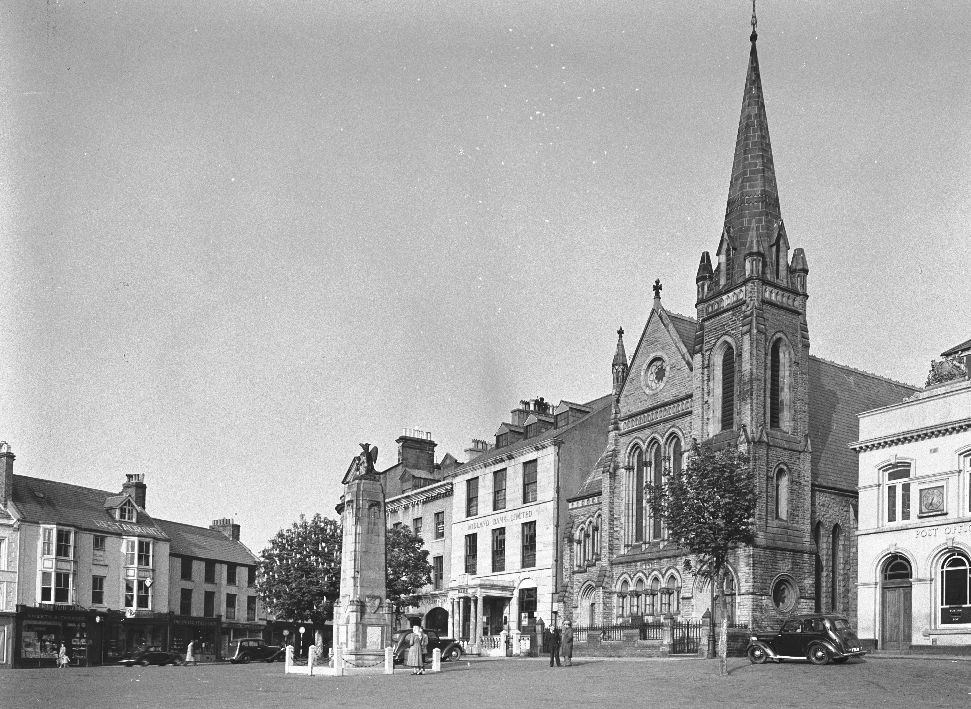

Durch das Hauptthor, das sich zwischen zwei großen runden Thürmen befindet, gelangten wir zum Mittelpunkte der Stadt. In dieser Gegend stehen mehrere alte Häuser, die durch ihre höchst sonderbare Bauart, welche der in deutschen Reichsstädten üblichen ähnlich ist, sich auszeichnen. Plas mawr house, der Inschrift zufolge 1691 ausgebessert, fällt unter ihnen besonders in die Augen. Der südliche Theil der, sich amphitheatralisch erhebenden, Stadt, ist der luftigste und freieste, und man hat, in der Nähe der letzten Häuser, eine schöne unbeschränkte Aussicht sowohl nach dem Meere, als nach den gegen Süden gelegenen Bergreihen zu.

From the castle we descended to the town. A part of its fortifications towards the sea, consisting of high walls with semi-circular towers, at regular distances, is still in very good condition. Between the walls and the sea there is a beautiful and smooth walk, kept with the neatness that has become natural to the English, which in fine weather is much frequented by the inhabitants of the town. A breast-work of stone, here and there interrupted by iron railings, runs along the sea-side; and a large square tower, projecting far beyond the wall, and opening on both sides towards the walk, has on the sea-side a large gate, and forms an entrance into the town. The prospect over the harbour and the opposite coast of Anglesea, is truly delightful.

Following the course of the town-walls along the sea side, we came to a small chapel, from which proceeded the sound of the organ and the accompanying voices of a number of children; allured by this, we turned round the corner of the wall, and entered by another gate, when we found ourselves in front of a neat and delightful little edifice in the Gothic style. We entered it for a few moments, and found it filled with well-dressed people of both sexes, who were singing with great devotion, and seemed to be very little disturbed by our entrance. On this side of the town (the eastern), are the dock-yards in which we saw several small craft, and two or three large vessels of about 150 to 200 tons, half-built. Some of the towers in the walls on this side seemed to be inhabited.

Entering the principal gate, which is flanked by two large round towers, we reached the centre of the town. In this part there are a number of old houses, distinguished by the singularity of their structure, which has a resemblance to that of the houses in the imperial towns of Germany. Among these we are particularly struck with Plas-Mawr-House, which, according to the inscription on it, was repaired in 1691. The southern part of the town, which rises in an amphitheatrical form, is the most open and airy, and where the houses terminate there is a beautiful and uninterrupted view both towards the sea, and the ranges of mountains to the south.

(Travels through England, Wales and Scotland in the Year 1816. Vol 2. London: 1820)

Reisen in England und Wales, 1842

Johann Georg Kohl (1808 – 1878)

Wir kamen gegen Abend nach Caernarvon, der Hauptstadt der Grafschaft gleiches Namens, und einer der größten Städte in Wales. Sie ist, wie die meisten Städte dieses Landes, von einheimischen Wälschen und von englischen Einwanderern bewohnt. Sie liegt unmittelbar an der Menai-Straße, und da sie rund umher wie Bangor und wie andere nordwälsche Orte, von „Slate-quarries“ (Thonschiefersteinbrüchen) umgeben ist, so besteht ihr Haupthandel in diesem scheinbar unbedeutenden Artikel, der aber eines gewissen Worts wegen, das man in allen englischen Fabrikorten und in allen Handelsstädten bei jeder Waare, nach deren Handelszielen man sich erkundigt, so oft als Antwort vernimmt, – ich meine das Wort: „All over the world!“ (über die ganze Welt hin!) – bedeutend geworden ist. Wenn man in Birmingham bei einem Knopfmacher nachfragt, wohin denn seine Knöpfe gehen, so antwortet er: „All over the world!“ (über die ganze Welt hin, Herr). – Fragt man einen Töpfer in den Staffordschen Potteries, wohin denn diese Art von Töpfen gehe, so heißt es: nach Amerika hin, nach Ostindien, nach Europa, „in fact, sir, aII over the world“ (in der That, Herr, über die ganze Welt), und erkundigt man sich hier in Caernarvon wieder, wohin die Slates gehen, so besinnt man sich auch nicht lange mit dem „All over the world!“

Die Schiefertafeln von Nordwales sind, wie gesagt, so vortrefflich, sie brechen in so großen Stücken, sie sind so elastisch und bröckeln so wenig, sie sind so schwarz und dabei erhält sich ihre Farbe, ohne zu grauen und zu verbleichen so beständig, daß man sie daher in aller Welt jetzt begehrt. Und namentlich in der allerneuesten Zeit sind sie so sehr begehrt, daß man ihre Ausfuhr und ihre Producierung in den Steinbrüchen als eben so im Zunehmen begriffen betrachten kann, wie die der Kohlen, und daß die Slates nicht nur die Hauptfrage für die Menai-Straße, sondern für diesen ganzen Theil von Nord-Wales geworden sind, eben so wie Eisen, seine Production und Ausfuhr die Hauptfrage für Südwales ist.

It was towards evening that we arrived at Caernarvon, the chief town of the county, and one of the largest in Wales. Like most Welsh towns, it contains a mixed population of native Welsh and English residents, and being surrounded by slate quarries, its chief commerce is in that article, one apparently insignificant, but which, like many a branch of British manufacture, acquires immediate importance in our eyes, when we are told whither it is carried for sale. Ask a Birmingham button maker whither his buttons go, and his immediate answer will probably be, ‘All over the world, sir.’ Ask a similar question of a maker of crockery in the Staffordshire Potteries, and you will receive the same answer; and here in Caernarvon, when I asked where all the slates went to, I was again told that they went ‘all over the world.’

They are so excellent, it seems, break into such large pieces, are so elastic, so little apt to crumble, so black, and their colour, at the same time, so durable that there is a demand for them ‘all over the world,’ particularly of late years, so much so that slates have become the staple article of produce for North, as iron is for South Wales.

(England, Wales, and Scotland. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.)

"Voyage au nord du pays de Galles", c. 1866

Arthur d’Arcis ( – )

Caernarvon est une ville de 9253 habitants à 37 kil. 500 de Llandudno Junction et le chef-lieu du comté de même nom. Édouard I, le conquérant définitif du pays de Galles, en ordonnant en 1283 la construction du château destiné à paralyser toute velléité de révolte de la part de ses nouveau sujets, fit surgir en même temps les murs de la ville. Celle-ci est en train de se développer soit par le fait du commerce favorisé par son port, soit par le fait des carrières d’ardoises de ses environs, soit enfin parce qu’elle est la clef de la véritable région montagneuse qui attire de plus en plus les touristes. Sa vieille enceinte est encore debout en grande partie et sur l’une de ses portes on a bâti l’hôtel de ville sous lequel passe une rue qui débouche sur le port. ... Il y a dix ans j’eus le plaisir de voir à plusieurs reprises, à Caernarvon même, des femmes qui portaient encore le vieux costume gallois : jupes noires, manteau rouge, et chapeau de feutre haute-forme. Les flots civilisateurs l’on fait disparaître et l’ont refoulé dans le sud du pays sans rien lui substituer, et c’est fort dommage parce qu’il ne manquait pas de caractère.

Caernarfon is a town of 9,253 inhabitants, 37.5 kilometres from Llandudno junction, and capital of the county of the same name. Edward I, the definitive conqueror of Wales, ordered the construction of the castle in 1283 with the aim of quashing any inkling of revolt on the part of his new subjects, and had the town walls built at the same time. The town is developing through commerce thanks to its port, through the surrounding slate quarries, and also through being key to the truly mountainous parts that are attracting more and more tourists. Its old walls are still largely intact and the town hall has been built on one of the gates, with the road that leads to the port running beneath it. ... Ten years ago I had the pleasure of seeing many times, actually in Caernarfon, women still wearing the ancient Welsh costume: black skirts, red coats and high felt hats. The tides of civilization have banished it to the south of the country, leaving nothing in its place, and it is a great shame because it was not without character.

Force commerciale de la Grande-Bretagne: côtes et ports maritimes, c. 1820

Charles Dupin (1784 – 1873)

Ville renommée pour la salubrité de sa position, et très-fréquentée durant la belle saison, par les baigneurs valétudinaires. On fait un commerce considérable dans le port de Caernarvon; la seule exportation des ardoises expolitées dans le comté, surpasse une valeur de 50,000 livres sterling, c’est-à-dire plus de 1,250,000 francs. Ces ardoises sont amenées, avec la plus grande économie, jusqu’aux lieux d’embarquement, sur des chemins de fer.

A town known for its salubrious position, and very busy with health-conscious sea bathers during the summer months. Caernarfon port does a considerable trade, slate exports alone, from the county’s quarries, are worth over 50,000 pounds, or more than 1,250,000 French francs. These slates are brought to the place of embarkment in the most economical fashion, on railway lines.