Caernarfon Castle - Overview

The Roman fort of Segontium was established on the outskirts of modern day Caernarfon as part of the campaign to subdue the Ordovices in AD77. This camp is mentioned in the story of ‘The Dream of Macsen Wledig’ found in the Mabinogion, a medieval collection of Welsh stories. Following the Norman Conquest, Hugh d’Avranches, Earl of Chester, built three castles across the north Wales, including one at Caernarfon, but by 1115 the Welsh had captured Caernarfon Castle alongside the kingdom of Gwynedd.

In 1283, after the conquest of Gwynedd, King Edward I began rebuilding Caernarfon Castle, reshaping it into a visible token of his rule over the newly acquired province. Modelled after the impressive walls of Constantinople, the towers were given a polygonal shape and coloured stones were set into horizontal stripes. To complete Edward’s display of power, stone eagles adorned the parapets of the highest tower in a play on the imperial past of Wales. Edward II was born at Caernarfon Castle in 1284, and Edward I transferred the title ‘Prince of Wales’ to his infant son to establish his dynastic control over Wales.

With the outbreak of the Glyndŵr Rising, the castle and town were repeatedly under siege by Welsh and allied French forces. With the accession of Henry Tudor to the English throne, Caernarfon Castle lost its significance and fell into decay. However, its defences remained in good enough condition to have been of use for the Royalists garrisoned here during the English Civil War. After this brief period of struggle, the castle was abandoned.

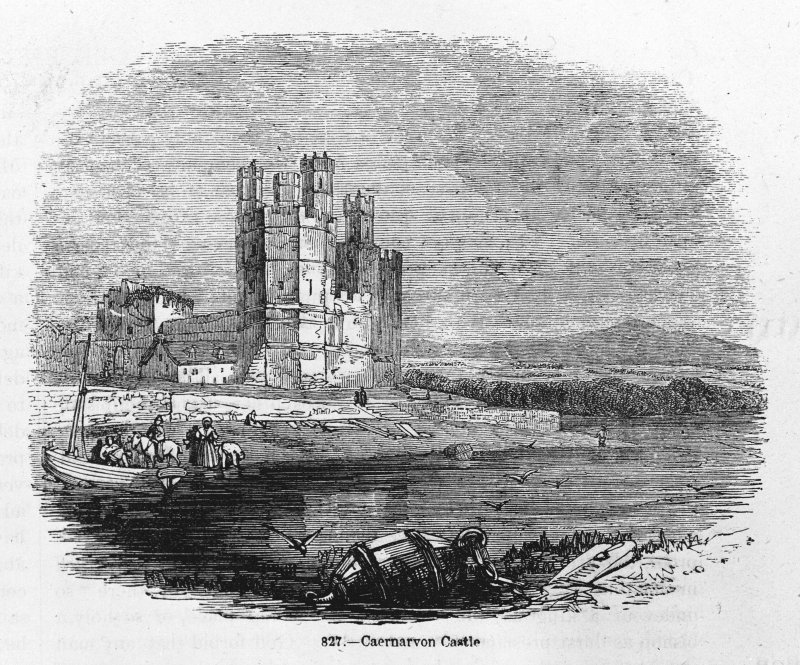

During the Romantic period, tourists started arriving in rising numbers as they took particular interest in the ruined, ivy-covered ruins of Wales. As a result, Caernarfon Castle underwent extensive restoration and conservation work in the late nineteenth century. In 1986, Caernarfon was recognised as part of the UNESCO’s Castles and Town Walls of Edward I World Heritage Site together with Conwy, Beaumaris and Harlech. Today, Caernarfon Castle is maintained by Cadw.

Accounts of Travel

Reise durch England, Wales und Schottland im Jahre 1817, 1816

Samuel Heinrich Spiker (1786 – 1858)

Wir sahen das Castell zuerst von der Südseite, und hier den Eingang, durch welchen, wahrscheinlich über eine Zugbrücke, die über den Graben führte, Eleonore, die Gemahlin Edwards I., in das Schloß einzog. Es ist aus zwei verschiedenen Steinarten, einer grauen und einer bräunlichen, erbaut, welche durcheinander gemischt sind; über dem Haupteingange steht in einer Nische die lebensgroße Bildsäule Edwards I. in Sandstein ausgehauen und noch ziemlich wohl erhalten. Der König ist in vollständiger Rüstung und drohend das Schwert ziehend dargestellt. – Die Räume, in welchen die doppelten Fallgatter lagen, sind noch jetzt deutlich zu bemerken, und die alten Angeln des Burgthores trotzen der Zerstörung der Zeit mit eben so gutem Erfolge, als die übrigen Bestandtheile des Schlosses.

Das Castell bildet ein längliches Viereck, das einst auf allen Seiten mit Thürmen von verschiedener Gestalt, viereckt, sechseckt und achteckt, umgeben war. Unter den acht bis zwölf noch vorhandenen sind am wenigsten die verfallen, welche an der Nord- und Südseite des Castells stehen, und namentlich der hohe Adler-Thurm (eagle tower), dessen Treppe so wohl erhalten ist, daß man auf ihr bis zur Spitze gelangen kann, von der man eine schöne Aussicht über den Menai und Anglesea genießt. Das Stein-Bild des Adlers, nach welchem der Thurm benennt worden, ist noch auf der Spitze desselben zu sehen, aber nur mit Hülfe der Einbildungskraft für einen Vogel zu halten. Als Merkwürdigkeit zeigt man in diesem Thurme das Zimmer, in welchem angeblich, Edward II. geboren wurde. Sein Vater, Edward I., schickte seine Gattin, Eleonore von Castilien, nach Caernarvon, um dort entbunden zu werden, damit die unruhigen Welschen, welche gelobt hatten, sich nur einem unter ihnen geborenen Prinzen zu unterwerfen, einen Herrscher dieser Art erhalten sollten. Seit dieser Zeit führt der englische Thronerbe den Namen „Prinz von Wales.“ – Der Kamin, durch welches das kleine Zimmer erwärmt wurde, in welchem Edward das Licht der Welt erblickte, ist noch vollkommen erhalten. Ein Spaziergang im Innern des Hofes längs den Mauern (die in den Thürmen die ungeheuere Dicke von 8–10 Fuß haben) gewährt angenehme Aussichten über die Stadt und den mit kleinen Fahrzeugen angefüllten Hafen. Der Hof, welcher sich nach der Südseite des Castells, gegen das Thor der Königin Eleonore, bedeutend erhebt, ist von allem Schutt gereinigt und mit Gras überwachsen. Wir fanden zwei, im letzten spanischen Kriege eroberte, metallene Sechspfünder, 1790 gegossen, mit dem Namenszuge Carls IV. und den Namen el codicioso und el escarbajo bezeichnet, auf demselben stehen. Der Blick auf die Mauern umher, die mitunter noch so unversehrt sind, daß man die inneren steinernen Fensterverzierungen vollständig erkennt, hat etwas ungemein imposantes.

We first saw the castle from the south side, where there is an entrance, through which Eleanor, the consort of Edward I. entered the castle, probably by a draw-bridge over the moat. It is built of two different kinds of stone, the one gray and the other of a brownish colour, which are intermixed. In a niche over the principal entrance, there is a figure of Edward I. in sand-stone as large as life, and still in tolerable preservation. The king appears in full armour, and in a threatening attitude, in the act of drawing his sword. The places in which the double portcullisses stood may be still distinctly recognized; and the old hinges of the castle-gates bid defiance to the destructive tooth of time as successfully as the rest of the castle.

The castle forms an oblong square, which was once surrounded on all sides by towers of various figures, quadrangles, hexagons, and octagons. From eight to twelve of these towers still remain; among which those on the north and south sides are least decayed. The stair of the lofty Eagle Tower in particular is still in such good preservation that we can ascend to the very top, whence there is a beautiful view over the Menai and Anglesea. The stone figure of the eagle, from which the tower has derived its name, is still to be seen at the top, but it requires the aid of the imagination to see in it the form of a bird. Among the remarkable objects in this town, we are shown the room in which it is said Edward II. was born. His father, Edward I. sent his consort Eleanor of Castile to Caenarvon, to be there delivered, in order that the turbulent Welshmen, who had sworn to submit to none but a prince born among themselves, might have a sovereign of their own nation; and from that time, the heir to the English throne has always borne the title of Prince of Wales. The fire-place which warmed the little room where Edward first saw the light, is still in perfect preservation. A walk in the interior of the court along the walls, that are of the enormous thickness of from eight to ten feet, affords delightful views over the town and the harbour, which is filled with small vessels. The court, which rises considerably on the south side of the castle, towards Queen Eleanor’s gate, is cleared of all rubbish, but is overgrown with grass. We found in it two Spanish six-pounders of brass, cast in 1790, taken in the last Spanish war, and marked with the initials of Charles IV. and the names of ‘el Codicioso,’ and ‘el Escarbajo,’ on them. The appearance of the surrounding walls, which are in many places in such good preservation that we can still perfectly distinguish the internal stone ornaments of windows, is uncommonly striking.

(Travels through England, Wales and Scotland in the Year 1816. Vol 2. London: 1820)

Briefe eines Verstorbenen, 1828

Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785 – 1871)

Ich war doch ein wenig von den letzten vier und zwanzig Stunden angegriffen, und begnügte mich daher heute mit einem Gange nach dem berühmten, hier liegenden Schlosse, welches von Eduard I., dem Eroberer von Wales, erbaut und von Cromwell zerstört, jetzt eine der schönsten Ruinen in England bildet. Das Einzige, was ich dabei bedaure, ist, daß es so nahe an der Stadt und nicht einsam im Gebürge steht. Die äußern Mauern, obwohl verfallen, bilden doch noch eine ununterbrochene Linie, welche ohngefähr drei Morgen Landes umschließt. Der innere, mit Gras bewachsene, mit Schutt und Disteln jetzt gefüllte Raum ist nahe an 800 Schritt lang. Sieben Thürme, schlank und vest gebaut, von verschiedener Form und Größe, umgeben ihn. Einer derselben ist noch zugänglich, und ich erstieg auf einer hinfälligen Treppe von 140 Stufen seine Platform, wo man eine imposante Aussicht auf Meer, Gebürge und Stadt hat. Beim Hinabgehen zeigte man mir die Rudera eines gewölbten Zimmers, in welchem, der Tradition nach, Eduard II., der erste Prinz von Wales, geboren ward. ...

Ueber dem großen Hauptthore steht noch Eduards steinernes Bild, mit der Krone auf dem Haupt, und einem gezückten Dolch in der Rechten, als wolle er nach sechs Jahrhunderten noch die Steintrümmer seines Schlosses bewachen. Ueber Entweihung hatte er auch heute mit Recht zu klagen, denn, inmitten der Ruine, machte auf dem grünen Platze ein Kameel, nebst Affen in rothem Tressenrocke, seine Kunststücke, und jubelnd stand eine zerlumpte Menge umher, sich des jämmerlichen Contrastes nicht bewußt, den sie mit den ernsten Ueberresten der sie umgebenden Vergangenheit bildete.

Der Thurm, in welchem der Prinz geboren ward, heißt der Eagletower (Adlerthurm), aber nicht von ihm rührt diese Benennung her, sondern von vier colossalen Adlern, welche die Spitze krönten, und von denen noch einer vorhanden ist.

I was still somewhat fatigued by my yesterday’s expedition, and contented myself with a walk to the celebrated castle built by Edward I. the conqueror of Wales, and destroyed by Cromwell. It is one of the most magnificent ruins in England. The only thing to regret is, that it stands so near the town, and not in solitary grandeur amid the mountains. The outer walls, although in ruins, still form an unbroken line, enclosing nearly three acres of ground. The interior space, overgrown with grass and filled with rubbish and with thistles, is nearly eight hundred paces long. It is surrounded by seven slender but strong towers, of different forms and sizes. One of them may still be ascended, and I climbed by a crumbling staircase of a hundred and forty steps to its platform, whence I enjoyed a magnificent view over sea, mountains, and town. On descending, my guide showed me the remains of a vaulted chamber, in which, according to tradition, Edward II., the first prince of Wales, was born. ...

Over the great gate still stands the statue of Edward, with a crown on his head and a drawn dagger in his right hand, as if after six centuries he were still guarding the crumbling walls of his castle. He might justly have broken out into indignant complaint at the desecration I witnessed. In the midst of these majestic ruins, a camel and some monkies in red jackets were performing their antics, while a ragged multitude stood shouting and laughing around, unconscious of the wretched contrast which they formed with these solemn remains of past ages.

The tower in which the prince was born is called the Eagle Tower; not from that circumstance, but from four colossal eagles which crowned its pinnacles, one of which is still remaining.

(Tour in England, Ireland, and France, in the Years 1828 & 1829. With Remarks on the Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants, and Anecdotes of Distinguished Public Characters. In a Series of Letters. By a German Prince. Ed. B – . Vol. 1. London: Effingham Wilson, 1832)

"Au pays de Galles", c. 1900

Firmin Roz (1866 – 1957)

A Caernarvon, le rêve devient une révélation. Ce n’est pas un château, ce n’est pas une forteresse, ce n’est pas une citadelle: Caernarvon, c’est l’idée de la conquête, matérialisée dans la pierre, c’est la volonté du vainqueur qui a pris corps et s’est appesantie sur le sol. La masse colossale se dresse avec une raideur d’anathème pour imposer à la nation vaincue l’immobilité éternelle et l’éternel silence. La dureté de ses hautes murailles tombe à pic, comme un arrêt du destin; elles sont nues, sans fenêtres, pareilles à des vouloirs fermés.

Contre sa domination, tout effort et tout espoir se brisent: aux plaintes de la servitude, aux grondements de la révolte, elle n’oppose que des pans inaccessibes et le geste droit de ses tours. Elle semble moins édifiée par des ouvriers humains que par quelque génie de la légende, aux temps héroïques où les Kymrys attendaient le retour d’Arthur. Ou bien encore on pourrait croire, sans l’architecture qui règle cette majesté, à quelque construction des Titans préhistoriques, dans un âge de pierre. Mais entrons: la forteresse s’humanise. Toute sa vie est tournée en dedans, vers l’enceinte où s’abritait le vainqueur. Des hommes ont vécu là, de la vie féodale; et nous pouvons lire les détails de leur existence dans les ruines qui subsistent et les indications jalonnées sur le sol.

Nous les voyons campés comme en pays ennemi, en éveil contre les surprises, approvisionnés pour les longs sièges. Et dans une des tours, entre quatre murs épais, voici la chambre obscure où naquit le fils aîné d’Édouard. Le roi l‘éleva, dit-on, dans ses bras, et paraissant à une fenêtre du château, le présenta au peuple assemblé: « Il est né Gallois; ce sera votre prince ». C’est ainsi qu’Édouard de Caernarvon fut créé prince de Galles, et inaugura la tradition qui fait porter ce titre au fils aîné des souverains d’Angleterre. La couronne du Gwynedd avait changé de maison, – et de patrie.

At Caernarfon the dream became a revelation. It is not a castle, it is not a fortress, it is not a citadel: Caernarfon it the idea of conquest, materialized in stone. It is the will of the conqueror incarnated and weighing heavily on the ground. The huge mass rises up abruptly in utter condemnation, to impose on the conquered nation eternal stasis and silence. These severe, high walls form a sheer drop, like a decree of destiny; windowless, bare walls, like desires shut down.

In the face of its domination, all effort is thwarted, all hope dashed: to complaints of servitude, and rumblings of revolt, it simply offers its impenetrable sides and the uprightness of its towers. It seems less built by human workers than by some genius from legend, from the heroic age when the Kymrys awaited the return of Arthur. Or you might think, if it weren’t for the architecture that rules this grandeur, that it was constructed by prehistoric Titans in some stone age. But let us enter: the fortress becomes more human. Its whole life is turned inwards, towards the enclosure that protected the conqueror. Men have lived here, a feudal life; and we can read the details of their existence in the ruins that remain and the clues on the ground.

We see them camped as if in enemy territory, on the lookout for attacks, ready for long sieges. And in one of the towers, within four thick walls, here is the dark room where Edward’s first son was born. The King took him, so they say, in his arms, and appearing at one of the castle’s windows, presented him to the people that had gathered there: ‘He is born Welsh, he will be your prince.’ This is how Edward of Caernarvon was made Prince of Wales, inaugurating the tradition that bestows this title on the firstborn son of English sovereigns. The crown of Gwynedd had changed house, and fatherland.

"Voyage dans le pays de Galles", 1862

Alfred Erny (1838 – )

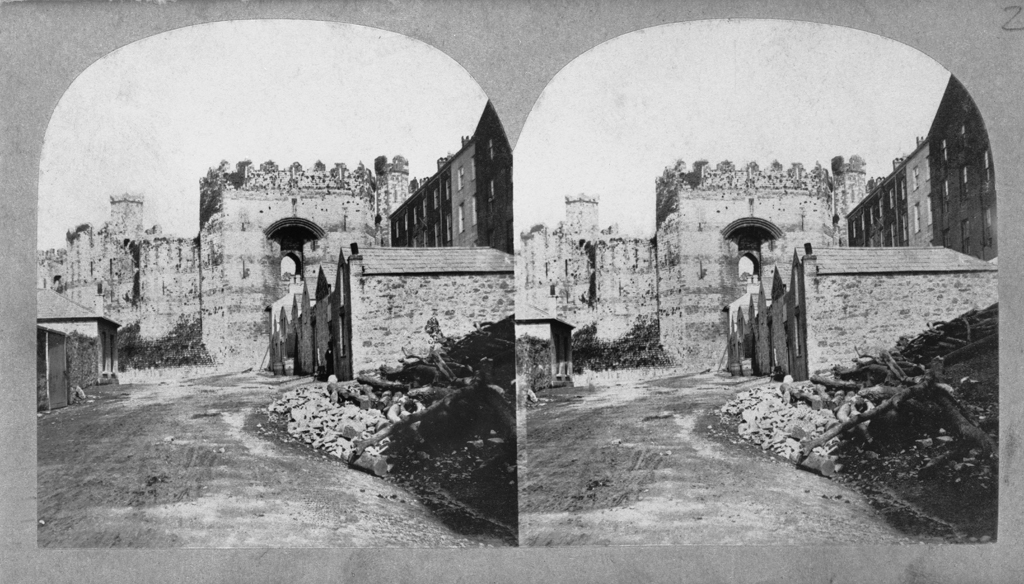

Je profitai de cette belle journée pour visiter le château de Caernarvon, une des belles ruines du pays de Galles. Il est situé sur un rocher au bord de la mer; malheureusement les maisons qui l’entourent de plusieurs côtés empêchent d’en saisir d’un coup d’œil tout l’ensemble.

Les murs ont sept pieds d’épaisseur; ils relient un grand nombre de tours qui communiquent entre elles par une triple galerie. La plus haute et la plus belle des tours est celle de l’Aigle, qui était anciennement surmontée d’un aigle en pierre. On monte jusqu’au faîte par un escalier de cent cinquante-huit marches. J’y suis resté longtemps à contempler la belle vue qui s’étendait autour de moi.

Dans la partie basse de cette tour, on me montra une petite chambre, où naquit, dit-on, Édouard II, le premier prince de Galles, de sang étranger. Quand Édouard Ier, son père, devint maître du pays de Galles, le district de Snowdon fut le plus difficile à soumettre; pour le dominer il éleva les châteaux de Conway et de Caernarvon bâtis sur les plans, dit-on, de ceux qu’il avait vus en Palestine. On regrette, dans cette belle ruine, l’absence du lierre qui orne d’une façon si pittoresque tant d’autres vieux châteaux. Dans une petite niche au-dessus de l’entrée apparaît la statue du fondateur, tenant dans sa main gauche une épée qu’il remet au fourreau selon les uns, et dont, selon les autres, il menace ses nouveaux sujets.

I made the most of this fine day by visiting Caernarfon castle, one of Wales’s beautiful ruins. It is situated on a rock on the seashore; unfortunately the houses that surround it on many sides prevent you from appreciating the whole in one go.

The walls are seven feet thick; they link a great number of towers that connect with each other by way of a triple gallery. The highest and most beautiful of these towers is that of the Eagle, which was once topped by a stone eagle. You climb to the top by a staircase of one hundred and fifty eight steps. I stayed there a long time, looking at the beautiful view that stretched out before my eyes.

In the lower part of this tower I was shown a little room where it is said that Edward II was born, the first Prince of Wales of foreign blood. When his father, Edward I, becamse master of Wales, the Snowdonia area proved the most difficult to subdue. In order to dominate it he built the castles of Conwy and Caernarfon, and is said to have based them on the plans of castles he had seen in Palestine. The lack of ivy, that is such a picturesque addition to so many other old castles, is a shame, on such a beautiful ruin. In a little recess above the entrance stands a statue of the founder, his left hand holding a sword that he is, according to some, returning to its sheath, while for others he is using it to threaten his new subjects.