Cardiff - Overview

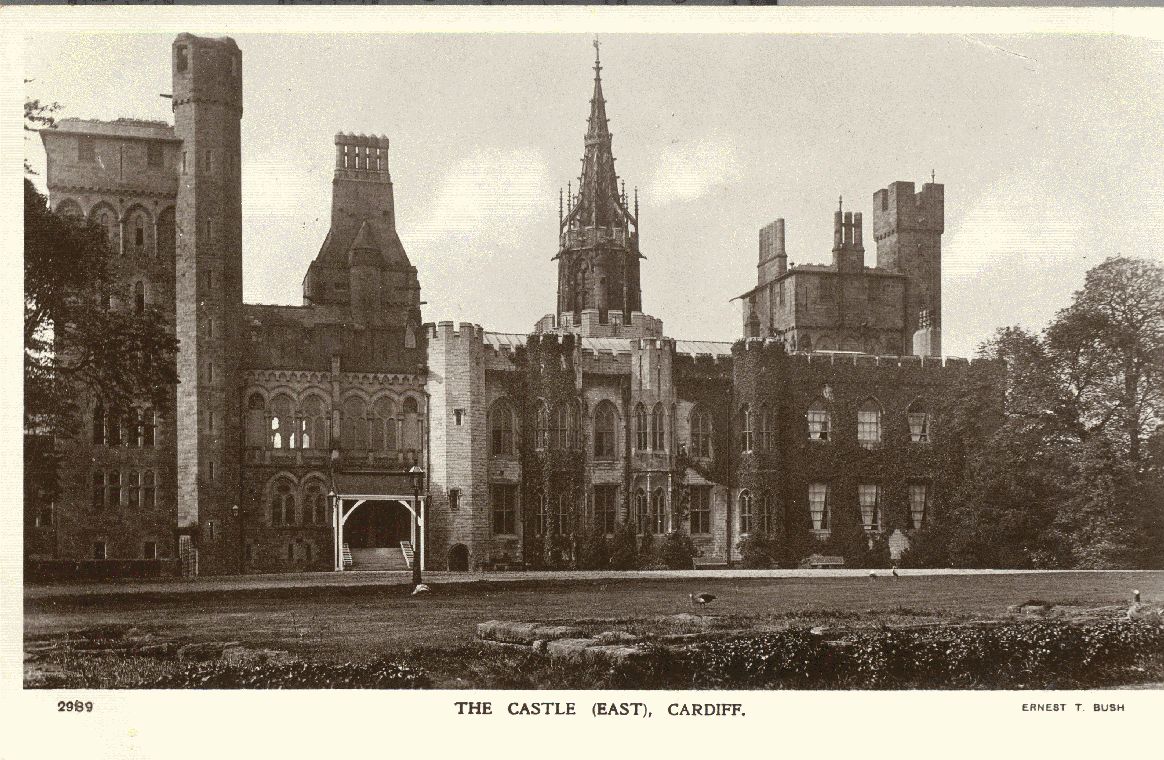

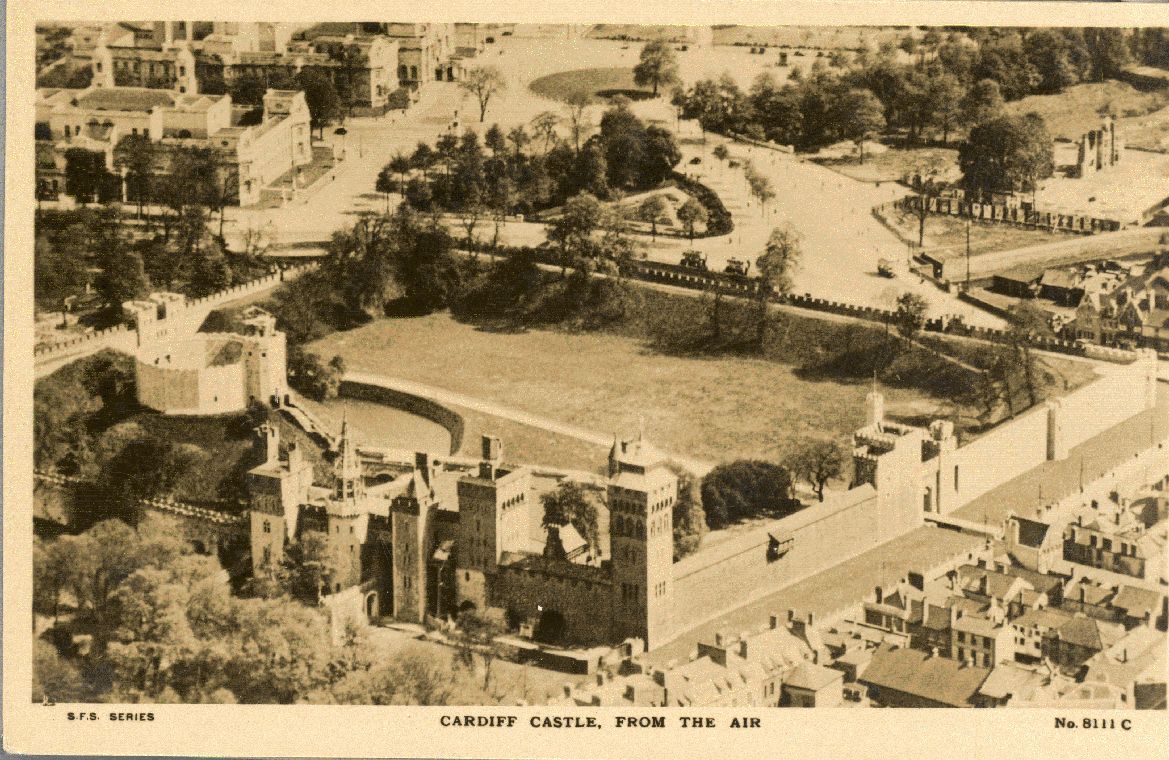

Although the region shows extensive evidence of Prehistoric occupation, the origins of the Welsh capital lie with the establishment of a Roman fort c.55 AD, which was occupied until the late fourth century. In the early medieval period Meurig ap Tewdrig formed the small kingdom of Glywysing, which survived until the Norman invasion in the eleventh century. William I, King of England, commissioned the building of a castle on the site of the former Roman fort and a small, walled, market town quickly developed around it. Despite having been burned by Owain Glyndwr in 1404, the town maintained a healthy maritime trade, which by the sixteenth century stretched to France and the Channel Islands as well as to other ports around Britain. While Cardiff became the county town of Glamorgan in 1536 and underwent numerous improvements in the eighteenth century, including the expansion and rebuilding of Cardiff Castle by the 1st Marquis of Bute, growth was limited and it was dismissed as "an obscure and inconsiderable place".

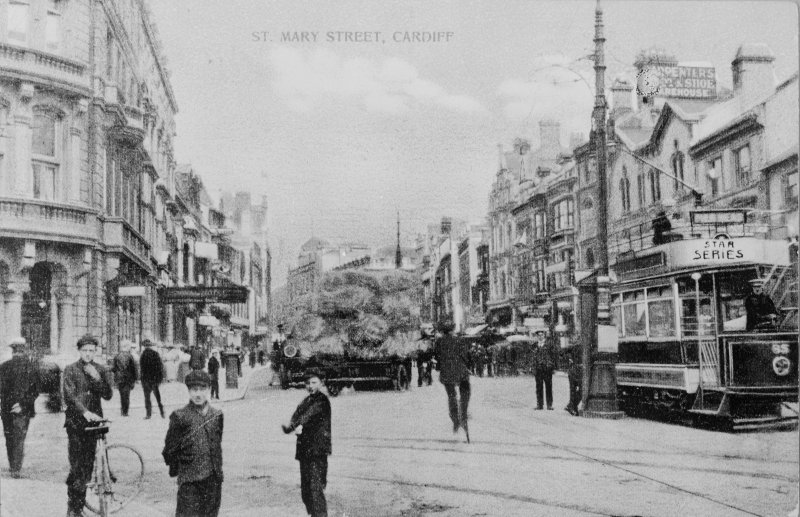

Large scale growth and development started in the last decade of the eighteenth century when the building of canals to link the town to the coal mining regions to the north, and the sea basin, started Cardiff’s transformation into the largest coal exporting city in the world. In the 1830s the 2nd Marquess of Bute (the ‘Creator of Modern Cardiff’) built docks in Cardiff Bay, where prominent buildings include the Coal & Shipping Exchange and the Pier Head Building, and the town entered a period of rapid population growth with a subsequent expansion of its town limits and economic and industrial development. Much of the growth of the town was driven by immigration, highly visible in the multicultural character of the boroughs around the docks, most famously among them Tiger Bay. By the time of the 1881 census, Cardiff was the largest town in Wales; in 1905 it was granted city status, subsequently acquiring the National Museum of Wales, the headquarters of the University of Wales and the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Wales. In 1955 it was made the capital city of Wales, and after the creation of a devolved National Assembly Government for Wales in 1997, hosts the Senedd. It also houses the Millennium Stadium, home to Wales’ national rugby team.

As sign of its international reputation and significance in the revival of Celtic languages and cultures along the west Atlantic coast, the National Eisteddfod held in Cardiff in 1899 was attended by a large delegation of writers, collectors of folklore, journalists and translators from Brittany. The Bretons eagerly reported home about their experiences, one and all praising the liveliness and model character of Welsh-language culture together with the splendour of the city.

Accounts of Travel

Dawlais Works, die Eisen- und Schienen-Walzwerke des Hauses John Guest, in London, 1844

Carl Klocke ( – )

Zu Wasser in Cardiff ankommend, landet man an der mächtigen Schleuse des neuen Docks und mit dem ersten Schritte an’s Land betritt man auch schon den Bereich der Eisenwerke von Dawlais, in deren letztem Ausläufer, dem Verschiffungsplatze. Die Flut steigt hier bis zu einer Höhe von 25 Fuß, daher die im Dock liegenden Schiffe, zur Zeit der Ebbe ziemlich hoch über dem Ankommenden auf dem Lande zu liegen scheinen. ...

Cardiff liegt in einer großen üppig frischen Ebene, im Norden geschützt durch die aufsteigenden Gebirge von Wales. Von diesen Höhen aus übersehen, gleicht die Ebene einem schönen englischen Parke. Eine solche Lage, mit der erfrischenden See im Süden, trägt augenfällig dazu bei, die Reize des im Westen von England bekanntlich so schönen Klima’s noch zu erhöhen. Die Milde und das, bei aller Wärme, doch Erfrischende der Luft ist entzückend und schien mir wunderbar belebend. Diese herrliche Ebene durchschneidend, führt die Eisenbahn in ein liebliches, von frischem Laubholz bedecktes Gebirge, mit freundlichen Seitenthälern, einer malerischen Ruine vorbei, im Thale des Flüßchens Taff entlang, bis etwa zur Hälfte des Weges nach Merthyr, wo die Bahn einen ansehnlichen Berg hinauf geführt ist. Hier werden die Züge durch eine obsenstehende Dampfmaschine, und nach Umständen mit Hülfe des Gegengewichts eines gleichzeitig hinunter gehenden Zuges hinaufgebracht, und hier an diesem Berge ist zugleich der einzige, mit einem zweiten Geleise versehene Ausweichepunkt dieser nur eingeleisigen Bahn. Als eine Probe, mit welcher Leichtigkeit und sichern Gewandtheit die Lokomotivführer ... verfahren, sah ich hier mehrere Male, daß, als der von Cardiff kommende Zug im langsam auslaufenden Tempo dem Berge sich näherte, die Lokomotive von dem Zuge sich trennte und dann in einem schnelleren Tempo sich vorwärts bewegte, um am Ausweichungspunkte früher anzukommen und in das Seitengeleis zu gehen, eher der Zug dort ankam, der alsdann das Geleis wieder nach seinem Bedürfniß gestellt stand und allein bis an den Berg lief, wo die stärkere Steigung ihm Halt gebot. ... Diese eingeleisige Bahn ... ist überhaupt im Vergleich zu den Hauptbahnen Englands, eine Miniaturbahn zu nennen. Das Geleis ist schmaler, der Erddamm nicht breiter, als die Sicherheit es erfordert, die Lokomotiven und alle übrigen Transportmittel sind dem entsprechend kleiner und leichter, die Schienen schwächer, Bahnhöfe und Stationshäuser durchaus auf das nothwendige beschränkt. Nichts überflüssiges, nichts luxuriöses ist sichtbar; – noch weniger aber fehlt etwas nothwendiges, und man erkennt überall den praktischen und richtig spekulirenden Sinn der Engländer.

Arriving by water in Cardiff, one lands at the enormous lock of the new dock and with the first steps on solid ground one is already entering the Dawlais ironworks with this shipping quay representing its outer limits. The tide rises up to 25 feet on this spot, which is why at low tide the docking ships appear to rise so far above the ground and the arriving passengers. ...

Cardiff is situated on a large, luxuriantly green plain, secured in the north by the rising mountain ranges of Wales. From these heights, the plain resembles a handsome English park. Such a situation, with the refreshing sea to its south, obviously contributes to enhancing the well-known charms of the agreeable climate in the west of England. The mildness and, despite the heat, refreshing quality of the air is delightful and appeared wonderfully reviving. The railway cuts through this magnificent plain and enters some lovely mountains, covered with fresh deciduous woodland and with friendly tributary valleys on either side, past a picturesque ruin, down the valley of the river Taff, and extends about halfway to Merthyr, where the train heads up a respectable incline. From here, the trains are winched uphill by a steam engine and, depending on the situation, the counterweight of a train descending the slope at the same time. Here on this hill is also the only location where a passing track has been laid down on this otherwise single track railway. As proof of the train drivers’ ease and surefootedness, ... I witnessed more than once how, as the decelerating train from Cardiff approached the mountain, the locomotive separated from the train and then continued at greater speed towards the passing track and entered it before the train arrived there. Once the tracks had been reset, the train then continued on its way up the hill, where the steeper incline provided the grip. ... In comparison to England’s main railways, this single track railway is but a mere miniature. The tracks are narrower, the embankment not much wider than safety demands; the locomotives and all other means of transport are correspondingly smaller and lighter, the tracks weaker, the stations and station buildings stripped down to the bare necessities. There is nothing superfluous or luxurious about it; however, none of the essentials is missing and everything reflects the practical and calculating mind of the English.

"Notizen über den Steinkohlenbergbau in England und Schottland", 1860

Gustav Pfähler (1821 – 1894)

In Cardiff, wo meist nur Gaskohlen verschifft werden, stehen die Preise loco Schiff 8–9 sh. pro Tonne der besten Sorte; geringere Sorten verhältnissmässig billiger. Die kleineren Kohlen werden selten verladen und verschifft.

Da durch Entwickelung von Gasarten in den Gaskohlen, welche in die Schiffe verladen sind, häufig Explosionen entstehen, ist an allen Ladeplätzen Cardiffs eine polizeiliche Bekanntmachung ausgehängt, nach welcher die Luken jedes mit Kohlen beladenen Schiffes, während dasselbe in dem Bute Dock liegt, geöffnet bleiben müssen und nicht eher geschlossen werden dürfen, als bis die Schiffe die Mündung nach dem Bristolkanal zurückgelegt haben. Die Nichtbefolgung dieser Maassregel ist mit einer Geldstrafe nicht unter 2 Lvr. und nicht über 5 Lvr. bedroht.

In Cardiff, which predominantly ships bituminous coal, the rates per ship stand at 8 to 9 Shillings per ton for the top grade; inferior grades are traded accordingly cheaper. The smaller coals are rarely loaded and shipped.

Due to the production of coal gas by the bituminous coal loaded on the ships, which may cause explosions, police announcements have been posted at all loading berths in Cardiff, demanding all portholes of coal-carrying ships to remain open while they are moored in Bute Dock and they must not be shut before the ships have passed through the estuary to the Bristol Channel. Failure to comply with this directive is threatened by no less than 2 Lvr., but no more than 5 Lvr.

"Chez Taffy: Quinze jours dans la Galles du sud", 1899

Charles Le Goffic (1863 – 1932)

C’est une de ces villes-champignons, comme il en pousse de temps à autre sur le terreau anglo-saxon. ... Cardiff est aujourd’hui le premier des ports charbonniers de l’Angleterre après Newcastle ... Cardiff est en effet, de tous les ports du monde, celui où le pavillon français est le plus fortement représenté. ...

L’admirable situation de Cardiff, au débouché du plus riche bassin houiller du globe, explique ce développenemt prodigieux de son trafic. Jusqu’en 1798, le charbon n’y arrivait qu’à dos de mules. Un premier progrès fut réalisé par la création du canal de Glamorganshire qui desservait toute la vallée du Taff, de Mirthyr-Tydfil à Cardiff, et communiquait par un ingénieux système d’écluses avec la manche de Bristol. Toutefois, c’est à partir de 1839, date de l’ouverture des docks, que la fortune commerciale de Cardiff prit son élan véritable. Si remarquables qu’ils aient été pour le temps, ces docks, construits par le second marquis de Bute et agrandis d’année en année au point de former une ville dans la ville, ne sont déjà plus suffisants: Cardiff est en marche vers son avant-port de Penarth et l’aura bientôt absorbé. De tous côtés, par de larges avenues, par des faubourgs manufacturiers, la ville gagne et s’étend. Les rues, tirées au cordeau, manquent peut-être d’imprévu. Du moins le « génie du progrès » n’a-t-il point été ici, comme chez nous, un génie destructeur. Cardiff a religieusement respecté tout ce qu’il a pu du passé, depuis sa vénérable église de Saint-John, avec le calme cimetière qui l’entoure et qui rayonne pacifiquement au cœur de la populeuse cité, jusqu’à cet admirable château du marquis de Bute, le Pierrefonds de la Grande-Bretagne, restauré avec une magnificence toute royale, comme pour mieux souligner dans un coin du parc la détresse romantique de l’Old Keep, l’antique donjon bâti par Fitzhamon en 1110, démantelé par Cromwell en 1632 et laissé tel, sur son tertre solitaire, que l’ont fait les années, les pluies d’automne et la griffe du Protecteur.

It is one of those mushroom towns, of the type that sometimes grows from Anglo-Saxon compost. ... Today Cardiff is the primary coal port of England after Newcastle. ... Cardiff is, in fact, of all the ports in the world, the one where the French nautical flag is best represented. ...

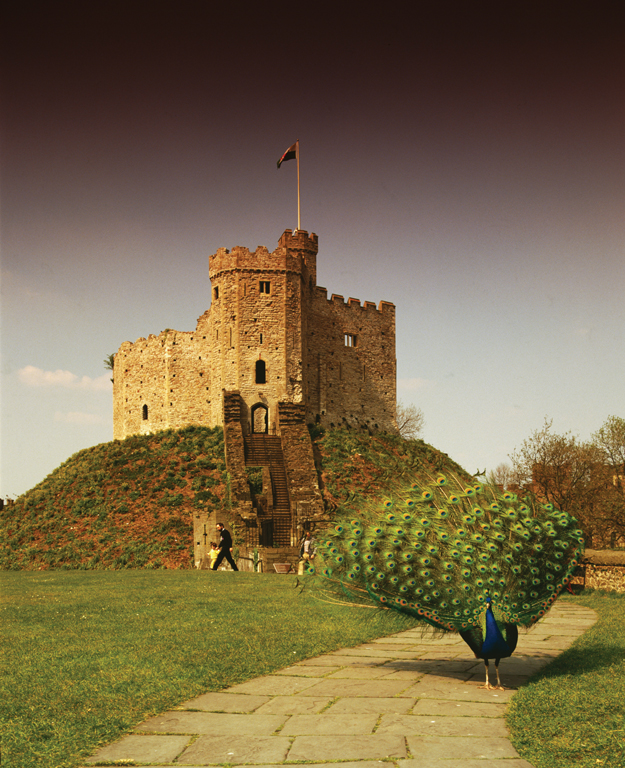

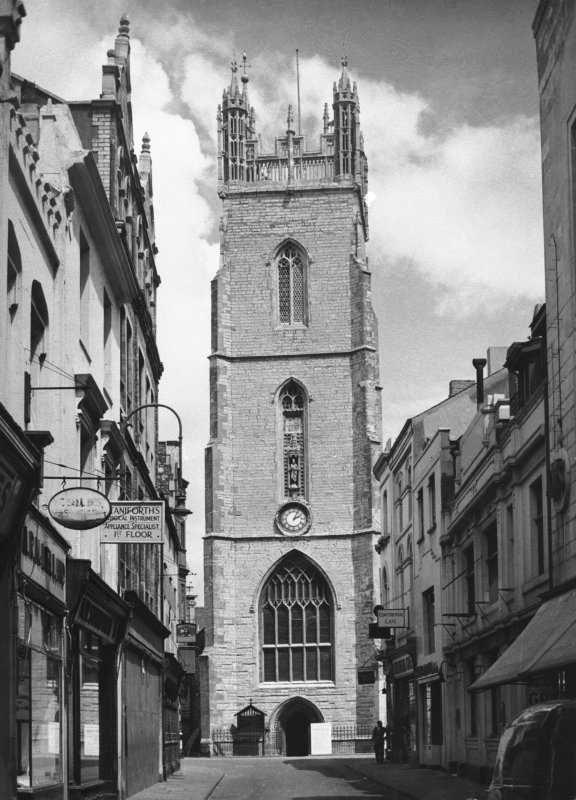

The enviable situation of Cardiff, at the opening of the richest coalfield on the globe, explains this phenomenal development and its trade. Until 1798, the coal only arrived there on the backs of mules. Initial progress was made with the creation of the Glamorganshire canal that served the whole of the Taff Valley, from Merthyr Tydfil to Cardiff, and was connected by an ingenious system of locks with the Bristol Channel. Nevertheless, it was from 1839, the date the docks opened, that Cardiff’s commercial fortune really took off. However remarkable they may have been for the time, these docks, built by the second Marquis of Bute and enlarged year by year to the point of forming a town within a town, are already inadequate: Cardiff is advancing towards its outer harbour at Penarth, and will soon have absorbed it. On all sides, by way of wide avenues, by manufacturing suburbs, the town is gaining and spreading. The streets, straight as a die, are maybe a bit predictable. At least here the ‘genius of progress’ has not here been a destructive genius, unlike at home. Cardiff has religiously respected all that it could of the past, from its venerated St. John’s Church, surrounded by its calm cemetery that radiates peace at the heart of the populous city, to the admirable castle of the Marquis of Bute, the Pierrefonds of Great Britain, restored with the most regal magnificence, as if to better underline in a corner of the grounds the romantic distress of the Old Keep, the ancient donjon tower built by Fitzhamon in 1110, dismantled by Cromwell in 1632 and left as it was, on its solitary knoll, rendered such by the years, the autumn rains and the stamp of the Protector.

"Chez Taffy: Quinze jours dans la Galles du sud", 1899

Charles Le Goffic (1863 – 1932)

Ces docks de Cardiff sont cependant une merveille et on les tient à juste titre pour des modèles du genre. A certaines heures de l’après-midi, leur animation est prodigieuse. Il faut aller là pour apprécier toute la valeur du proberbe anglais: Time is money. L’automatisme y est poussé à ses dernières limites; les wagons débouchent sur le port par longues files; leur chargement est immédiatement saisi par des grues hydrauliques qui le versent dans les soutes des navires. Tout cela est réglé à une seconde près et l’on sait exactement le nombre de minutes qu’il faut pour charger un millier de tonnes de houille. Des omnibus stationnent à la sortie des docks; nous grimpons dans le premier qui s’offre et la rentrée s’opère par les faubourgs ouvriers, noirs de monde, mais d’un monde sordide, loqueteux, et qui fait le plus trists contraste avec la population des autres quartiers. Il n’y a point que dans les villes de la Grande-Bretagne où l’on observe cette juxtaposition des trois sortes de quartiers – l’aristocratique, le marchand et l’ouvrier; – mais ce qui est proprement anglais, c’est que la population des une ne se mêle pas ou très peu à la population des autres: tous trois sont comme des villes différentes, qui ne communiquent pas entre elles et qui vivent chacune de leur vie propre.

These Cardiff docks, though, are a marvel and they are justifiably held up as models of their type. At certain hours of the afternoon their animation is phenomenal. You must go there to appreciate fully the English proverb: Time is money. Automation there is pushed to the latest limits; long lines of wagons unload at the port; their loads are immediately seized by hydraulic cranes that pour them into the ship holds. All this is regulated to the second so that the exact number of minutes required to load a thousand tonnes of coal may be calculated. Buses park at the exit from the docks; we got into the first one that came and returned by way of worker’s suburbs, black with people, but sordid people in rags, that form the saddest contrast with the populations of other neighbourhoods. It is only in the towns of Great Britain that this juxtaposition of three types of neighbourhood is to be seen – the aristocratic, the tradesman and the labourer; – but what is particularly English is that the population of one does not mix, or hardly mixes, with the population of the others. They are like three different towns that do not interconnect and that each lives its own life.