Conwy Castle - Overview

Conwy Castle was built by the English king Edward I between 1283 and 1287 as part of his conquest of Wales and is regarded as one of the finest examples of thirteenth-century fortified architecture. It was one of the key sites in Edward’s attempt to subject the Welsh to his rule by enclosing north Wales with an ‘iron ring’ of castles, supplied with goods and food by English colonies set up in adjacent fortified towns. Like all of his major Welsh castles, Conwy Castle is situated on the coast so that construction material and military supplies did not have to cross hostile terrain, but were instead delivered by boat. However, as Edward’s assets began to run thin by the early fourteenth century, the castle and town were poorly equipped and suffered from shortage of supplies.

In 1399, King Richard II found refuge here from the insurrection of Henry Bolingbroke, soon thereafter crowned King Henry IV. Two years later, the castle and town were again visited by insurgence as they were taken over by rebels under the leadership of Owain Glyndŵr. Although the castle was refortified during the Wars of the Roses, it played no significant part, but was successfully held for Charles I during the English Civil War.

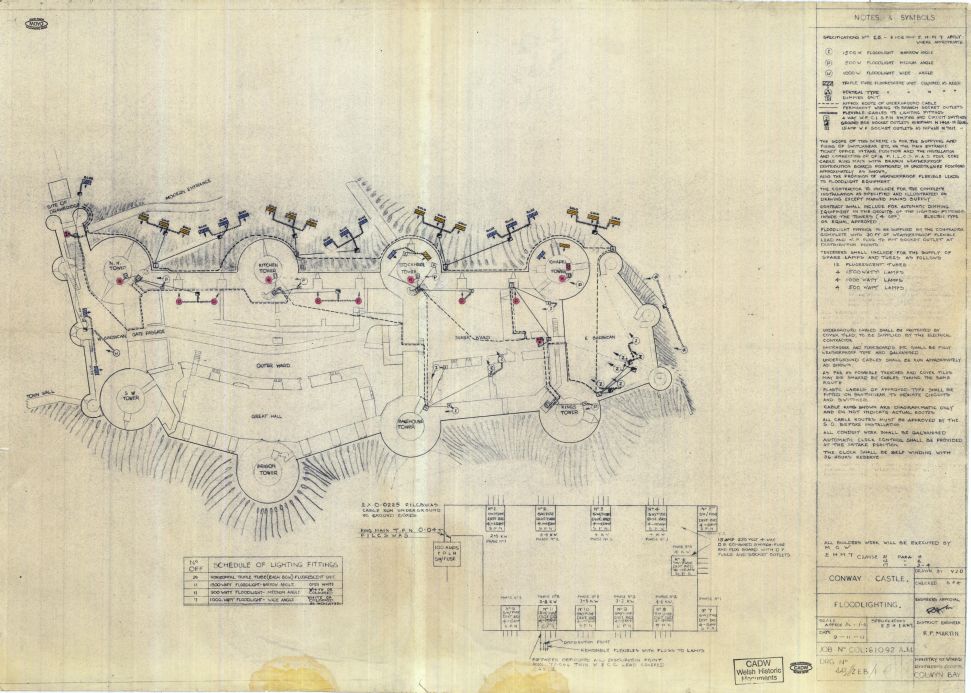

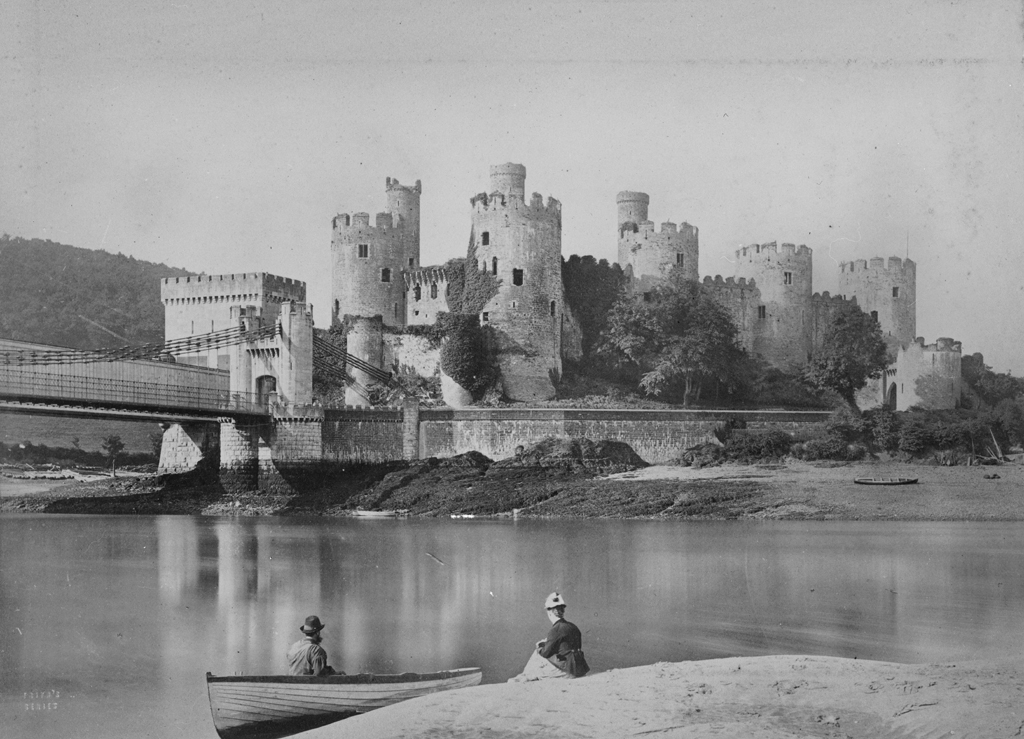

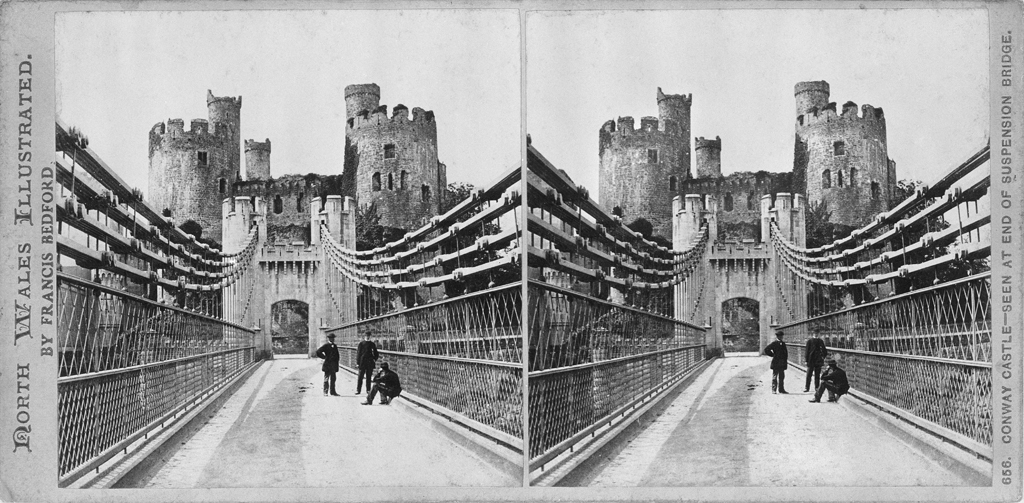

With the rise of modern tourism in the late eighteenth century, the now ruined castle became a chief picturesque travel destination on tourists’ journeys along the northern coast of Wales. After the construction of Thomas Telford’s suspension bridge and the Chester to Holyhead Railway, interest in its conservation increased and, in 1865, restoration works on the castle began after it passed into the ownership of the town. In 1986, Conwy was recognised as part of UNESCO’s Castles and Town Walls of Edward I World Heritage Site together with Beaumaris, Caernarfon and Harlech. Today, Cadw maintains Conwy Castle for the nation.

Accounts of Travel

Reise durch England, Wales und Schottland im Jahre 1817, 1816

Samuel Heinrich Spiker (1786 – 1858)

Zu Aberconway angekommen waren wir kaum im Gasthofe abgestiegen, als wir auch schon zum Castell eilten, dessen Trümmer uns schon von dem jenseitigen Ufer aus mächtig angezogen hatten. Es ward gegen das Ende des 13ten Jahrhunderts von Edward I. als ein Bollwerk gegen die Welschen erbaut und muß einst sehr stark gewesen seyn. Das Ganze scheint aus einem Viereck und einem Fünfeck, zu einem Ganzen verbunden, bestanden zu haben: acht runde Thürme, mit den Mauern verbunden, von denen drei gegen Osten, nach dem Flusse hin, zwei gegen Süden, ebenfalls nach dem Wasser, und drei gegen das Land hin stehen, vertheidigten es. Es hat zwei Höfe: auf dem größeren lag zur rechten die große Halle, deren Mauern, mit den Balkenlöchern und Fenstern darin, noch unversehrt stehen. Vier kolossale gothische Bogen, auf denen einst das Dach ruhte, trotzen ebenfalls noch der Zeit. In allen Thürmen (zwei oder drei ausgenommen, die vielleicht mehr von der Zeit gelitten haben) sind nach oben zu kleinere runde Thürme, als Warten angebracht; die Treppen, welche zu ihnen hinaufführten, sind indeß sämmtlich verfallen, und nur einige der unteren Stufen übrig, an denen man sehen kann, wie sie angelegt waren. Zu den drei Thürmen an dem Flusse sind die Zimmer noch ziemlich erhalten, und namentlich eines, dessen Decke noch ganz vorhanden ist, und an welches ein kleines Cabinet stößt, das man in die dicke Mauer hin eingebaut hat: die steinernen Bänke an den Wänden sind noch unversehrt, und man sieht im Geiste die einstigen Besitzer des Schlosses auf ihnen sitzend, in ihren Mußestunden zum Flusse und auf das gegenseitige Ufer hinabblicken, und sich an der Schönheit der Aussicht weiden. Sehr malerisch erscheint auch, auf der andern südlichen Seite, die gegenüber liegende sanft aufsteigende Anhöhe, mit frischem Gebüsch bedeckt. Sämmtliche Thürme und ein Theil der Mauern sind mit einer dichten Epheudecke überzogen; ein Schmuck, welcher diesen herrlichen Trümmern zu gebühren scheint.

On our arrival at Aberconway, we hastened from our inn to the castle, the ruins of which had already so strongly attracted our attention from the opposite bank. It was built by Edward I, about the close of the thirteenth century, as a bulwark against the Welsh, and in former times must have been of great strength. It appears to have consisted of a quadrangle and pentagon, connected together so as to form one whole. It was defended by eight round towers connected with the walls, three of which are on the east towards the river; two on the south also towards the river; and three on the land-side. It has two courts, in the largest of which, on the right stands the great hall, whose walls, with the holes for the beams and the windows in them, still remain uninjured. Four colossal Gothic arches, on which the roof once rested, still also bid defiance to time. In all the towers, with the exception of two or three (which may probably have suffered the most from age), there are smaller round towers at the top as watch towers, but the stairs that led to them are wholly in ruins, and a few only of the lower steps remain, whereby one may perceive the manner in which these stairs were constructed. In the three towers on the river the rooms are still in tolerable preservation, and particularly, one of them of which the roof still remains entire, and which has a small closet formed in the thick wall. The stone benches along the walls are still unimpaired, and we see in imagination the former occupiers of the castle sitting on them, in their leisure hours, looking down on the river and the opposite bank, and feeding their eyes with the beauty of the prospect. The gently swelling hills on the opposite side, covered with fresh looking trees and underwood, have also a very picturesque appearance. The whole of the towers, and a part of the walls, are cased with a thick mantle of ivy, an ornament which seems to suit well with these majestic ruins.

(Travels through England, Wales and Scotland in the Year 1816. 2 vols. London: 1820)

England, Wales, Irland und Schottland, 1802

Christian August Gottlieb Göde (1774 – 1812)

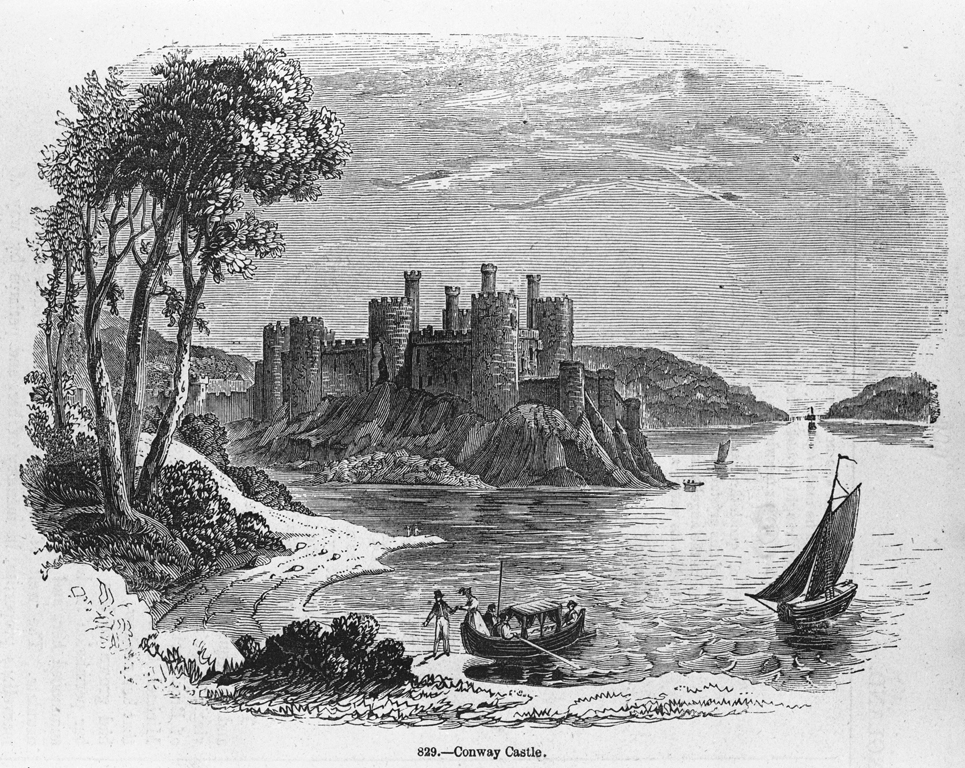

Diese Ruine ist von erstaunlichem Umfange und gewähret, von welcher Seite man sie auch betrachte, einen mahlerischen Anblick. Am schönsten nimmt sie sich aber doch wohl von der Wasserseite aus, und diesen Standpunct haben auch die meisten Englischen Landschaftsmahler und Zeichner, von denen sie oft abgebildet worden ist, gewählet. Im Innern der Festung ist noch ein großer Hof und eine schöne Halle ziemlich wohl erhalten, die von der prächtigen Anlage des Ganzen zeugen. An der Außenseite gegen den Fluß zu stehen noch acht ungeheuere, runde Thürme, zwischen denen jetzt wild aufgeschossene Bäume ihre Aeste ausbreiten. Aus den Spitzen dieser großen Thürme ragen kleinere hervor, wodurch das Ganze ein sehr sonderbares Ansehn erhält. Der Conway nimmt sich hier majestätisch aus. Er ist eine Englische Meile breit und in seiner Mitte liegt eine kleine, grün überwachsene Insel.

This ruin is of an astonishing size and offers a picturesque appearance from whichever side it is viewed. Perhaps, however, the most beautiful aspect is gained from the side of the river. This is the spot most frequently chosen by English painters and draughtsmen who have depicted the castle so often. A large courtyard and a beautiful hall are still well preserved inside the castle and give evidence of the magnificence of the entire structure. On the outside and towards the river, eight sublime round towers still stand; between them, untamed tall trees spread out their branches. From the tops of these towers, smaller ones protrude, which contribute to the most peculiar appearance of the whole. From this side, the river Conwy presents itself most majestically. It is one English mile wide and a small, overgrown green island is situated in its middle.

"Voyage au nord du pays de Galles", c. 1866

Arthur d’Arcis ( – )

A peine a-t-on dépassé la porte de la ville qu’on se trouve en face de l’entrée du château. Celui-ci, bâti au bord de la rivière sur un rocher escarpé, est défendu par huit tours rondes surmontées d’élégantes tourelles de vigie et reliées par des murs énormes. Cette enceinte est dans un admirable état de conservation, ce n’est qu’à l’intérieur que les salles sans plafond, les étages écroulés et les monceaux de débris offrent l’image de la dévastation. Actuellement on en prend le plus grand soin et on tire un excellent parti de ces ruines en entretenant le joli passage qui longe la crête des murs et permet de se faire une idée assez juste du plan de tout le château. La ville est entourée d’une enceinte formée par des tours reliées par de solides murailles percées de quatre portes. Son plan ressemble à une harpe, l’instrument favori des Gallois; mais l’intérieur ne réveille pas des idées poétiques, car il porte l’empreinte de la tristesse, de la décadence et de la misère. Toutefois une perle se cache au milieu de ces ruelles. C’est ce qu’on appelle la Plas Mawr ou le grand manoir. Il faut s’aplatir contre le mur d’en face pour saisir l’ensemble gracieux et élégant de sa façade, car cet édifice est situé dans une vraie ruelle arabe. Ses fenêtres, munies d’avant-corps travaillés comme une dentelle, nous rappellent aussi l’Orient. Une porte cochère nous introduit dans une cour carrée, d’où un escalier en spirale conduit aux salles spacieuses des deux étages. L’une d’elles, lambrissée de chêne, au plafond de stuc, à la cheminée monumentale, nous rappelle, à l’aide des monogrammes R. W., E. R. et R. D. les noms du fondateur, Robert Wynne, de la reine Elisabeth, Elisabeth régina, et de son favori, Robert Dudley, qui l’honorèrent de leur présence. Bâtie en 1585, elle était bien dégradée lorsqu’on eut l’heureuse inspiration de l’affecter, au commencement de 1886, à l’académie galloise des beaux-arts qui en prendra tout le soin qu’elle mérite.

You are hardly through the town gate when you find yourself facing the entrance to the castle. Built on a steep rock on the riverside, it is defended by eight round towers topped with elegant watch turrets and connected by enormous walls. This enclosure wall is in an admirable sate of repair, it is only on the inside that the ceiling-less rooms, fallen storeys and piled up debris present an image of devastation. It is receiving the best care at the moment, and these ruins are put to excellent use by maintaining the pretty passage that runs alongside the top of the walls and affords one a pretty good idea of the castle’s layout. The town is surrounded by an enclosure formed of towers connected by solid walls containing four doors. Its plan resembles a harp, the favourite instrument of the Welsh; but the interior awakens no poetic ideas, for it carries the imprint of sadness, decay and destitution. However, hidden among these little lanes is a real pearl, called Plas Mawr or the Great Manor. You must flatten yourself against the wall opposite in order to fully appreciate the grace and elegance of its facade, because this building is located in a real Arab lane. Its windows, furnished with tracery as fine as lacework, similarly recall the Orient. A carriage entrance leads into a quad, from which a spiral staircase leads to the spacious rooms of the two floors. One of these, oak-panelled, with a stucco ceiling and a monumental fireplace, displays the monograms RW, ER and RD to remind us of the names of the founder Robert Wynne, of Queen Elizabeth, Elisabetha Regina, and of her favourite, Robert Dudley, who honoured the place with their presence. Built in 1585, it was in a poor state of repair by the beginning of 1886, when it had the good fortune of being assigned to the Welsh Academy of Fine Arts, who will give it all the care it deserves.

"En pays de Galles", c. 1900

Édouard Gachot (1862 – 1945)

De la gare [i.e. Llandudno Junction], je vais pédestrement à Conwy. Ce qui m’attire de ce côté, c’est le vieux château, aperçu d’une passerelle. Château formidable autrefois, qui domine maintenant et la gare et le bourg. Ce fut un logis d’Édouard Ier, son Warwick-Castle, restauré au retour de Palestine et gardant les marques d’une architecture orientale. ... J’entre dans le vieux manoir. Aire et maison de prince, les tours et l’habitacle, en granit, ont bravé tout à tour les injures du temps et la fureur des flots poussés jusqu’à Conway par la mer. Dans les vastes escaliers et dans les longs corridors, chaque pas lève un écho. Sur les dalles de la cour, les valets de vingts princes ont laissé, profondément imprimée, la trace de leurs pas. La rouille a mangé les grilles des fenêtres et rongé l’armature des portes. Maintenant, le noir souterrain où moururent d’illustres prisonniers, est fermé. Du créneau de la maîtresse tour, la vue s’étend, vers le sud, très loin, au-dessus du pays boisé, tandis qu’au nord, elle embrasse tout le rivage que borne Landudno-les-Bains, et tombe, à l’ouest, sur Conway, vieille bourgade qui servait autrefois de caserne aux gens d’armes du roi.

From the station [i.e. Llandudno Junction], I go on foot to Conwy. What attracts me this way is the old castle, glimpsed from a bridge. A terrific castle in its day, that now dominates both the station and the town. It was a dwelling of Edwards I, his Warwick-Castle, restored on his return from Palestine, bearing the stamp of oriental architecture. I enter the old manor. Place and house of a prince, the towers of the abode, of granite, have braved one after the other the ravages of time and the fury of the water pushed as far as Conwy by the sea. In the vast staircases and the long corridors every step has an echo. On the flagstones of the courtyard, the servants of twenty princes have left, deeply imprinted, the trace of their steps. The rust has eaten the window bars and gnawed at the door surrounds. The black underground place where renowned prisoners met their deaths, is now closed. From the crenellations of the King’s Tower, the view southwards extends a long way over wooded land, and northwards it takes in the whole of the Llandudno coastline and falls, to the west, on Conwy, the old town that once served as barracks for the King’s soldiers.