Llanberis - Overview

Llanberis lies in a long, narrow valley with two large lakes just north-west of Snowdon. The earliest evidence of settlement is Dinas Ty Du hillfort dating from the Iron Age. Some Roman remains have been found and are most likely associated with Segontium, the large fort on the outskirts of modern day Caernarfon. In the sixth century, Saint Peris built a religious retreat at the southern end of Llyn Peris and Saint Padarn established his church on the banks of Llyn Padarn.

Until the early nineteenth century, the area remained sparsely settled and agriculture provided the main income. Small-scale open cast mining of slate along the north-eastern slopes of the valley, which had started in the late eighteenth century, developed dramatically with the opening of the Vivian Quarry in the 1870’s where the production was streamlined by employing blackpowder and further tramways were installed for improved transportation of the slates from the quarries. The largescale industrial mining greatly contributed to the growth of the population from around 700 in the first half of the nineteenth century to over 3000 by the end of it.

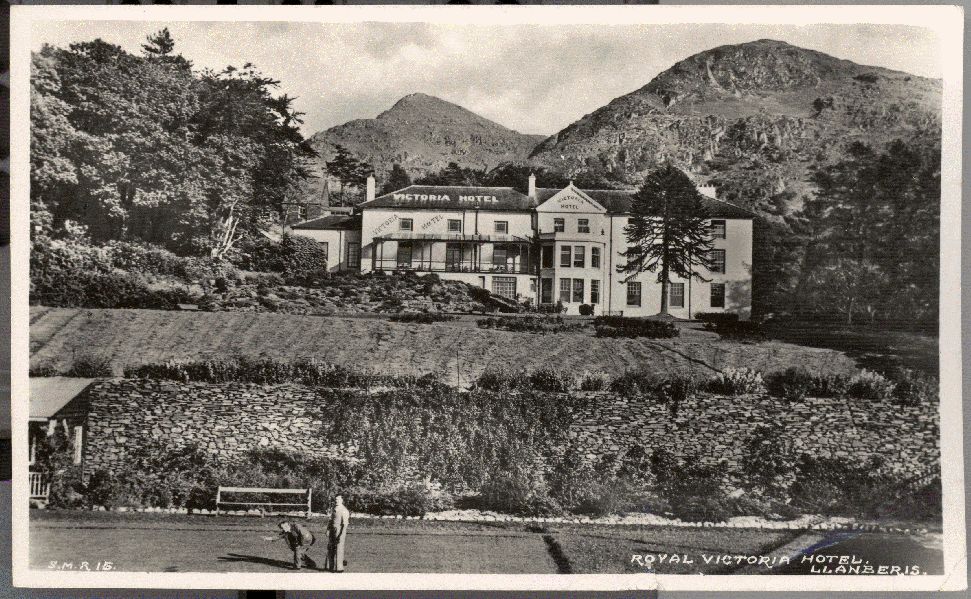

Despite the growth of industrial open cast mining in the valley, tourists came to Llanberis in ever rising numbers from the Romantic period onwards. The Royal Victoria Hotel advertised its provision of ponies and guides to the summit of nearby Snowdon and also held the keys for the grounds on which Dolbadarn Castle is situated. Julius Rodenberg, a journalist and travel writer from Germany, was taken in by the beautiful situation of the hotel and the hotel harper playing in the lobby every evening. Feeling particularly inspired one evening, he composed new lyrics on the tune of the Welsh folk-song ‘Ar hyd y nos’. Tourism is now the major industry in Llanberis, a centre for walking, climbing and mountain biking as well as diving in the now flooded slate quarry.

Accounts of Travel

Reisen in England und Wales, 1842

Johann Georg Kohl (1808 – 1878)

Hinter unserem Wirthshause befand sich in der Entfernung einer Meile ein großer Slatequarry, den wir zuerst besahen. Man sagte uns, daß in diesem Quarry jetzt wenigstens 1000 Menschen Beschäftigung fänden. Es gab noch mehre kleine in der Nachbarschaft des Ortes umher, und aus allen ertönte ein beständiges Krachen der Pulversprengungen und ein fast ununterbrochenes Poltern der von den Bergen herunterfallenden „Slate-slabs“ (Schieferblöcke). Der ganze Berg des Steinbruchs war gewiß bis zu einer Höhe von 1000 Fuß terrassirt, mit Stufen, deren jede nach meiner ungefähren Schätzung etwa 100 Fuß hoch sein mochte. Diese Stufen oder Terassen waren breit und groß, und jede war eine Scene des Steinsprengens und Steinbrechens. Auf mehren derselben polterten die Schieferblöcke herab und wurden hier sofort in die erwähnten Prinzessinen- und Herzoginnen-Formen gebracht und dann in großen Massen auf „slanting railroads“ (schiefe Eisenbahnen), die am Berge sich hinschlängelten, herabgebracht. Sonst soll es in diesem wilden Thale viele Adler gegeben haben. Die Leute versicherten mir aber, daß sie durch die Slatequarries und durch den unaufhörlichen Pulverdonner derselben daraus vertrieben worden seien.

Eine ihrer Hauptkunden, sagten sie mir, sei seit Kurzem das Kap der guten Hoffnung geworden, wo wahrscheinlich jetzt alle Häuser mit Schiefer gedeckt werden möchten. Das englische Gouvernment deckt seine öffentlichen Werke, wie sie mir sagten, fast überall mit Schiefer, und auch die englische Regierung ist daher einer ihrer vornehmsten Kunden.

Behind our inn was a slate quarry, to which we first directed our attention. In this quarry, we were told, upwards of 1000 persons were employed. There were several smaller quarries in the neighbourhood, and from all of them we heard a constant succession of explosions of gunpowder, and an almost uninterrupted noise caused by the slate slabs rolling down the hills. That on which the great quarry was situated, had already been cut into a succession of terraces to the height of 1000 feet, connected by a flight of steps each a hundred feet high, and on each the busy work of breaking and blowing up the stone was going on merrily. On several the blocks of slate were undergoing their metamorphoses into duchesses and princesses, and were then sent down, in large masses along the slanting railroads that wound themselves around the hill. [Once there were supposed to have been many eagles in this wild valley. The locals told me, however, that they have been chased from it by the slate quarries and the incessant thunder of powder.] One of their chief customers, some of the persons employed on the works told me, was the colony of the Cape of Good Hope, where, to judge from the great demand that has lately sprung up, almost every house must by this time be roofed with slates. [For that reason, the English government, too, is among of their most noble customers.]

(England, Wales, and Scotland. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844)

Ein Herbst in Wales, 1856

Julius Rodenberg (1831 – 1914)

Wo nun endlich das Dorf Llanberis beginnt, da schließen sich Tannen und Buchen lieblich zusammen und reizender als das Victoria-Hotel auf seinem Hügel unter Garten und Wald, ernst überragt von den Trümmern des Dolbadarn-Schlosses, hab’ ich nie eins liegen sehn. Dazu das eigenthümliche Leben, halb poetisch – halb humoristisch – schöne Engländerinnen mit wehendem Schleier aus jeder Gebirgsschlucht auf muthigen Ponies hervorsprengend,– Gentlemen, junge und alte, die mit ihren Bergstöcken, die Filzcylinder zerdrückt, die engen Hosen zerfetzt, die Hände zerrißen, vom Snowdon herabkommen; die Führer und die Laufjungen, die Esel und die Pferdchen, Alles durcheinander mit Lachen, Schimpfen, Brüllen und Wiehern – dazwischen das ewige Quinquelieren des Harfners, der auf der Flur des Hotels zwischen den Kleiderbrettern saß, und hoch über diesem bunten Treiben das Flattern der englischen Fahne, die ihren Schatten über die hellgrüne Rasenfläche und die Tannenwipfel am Fuße des Berges dahinwarf: das ist die Staffage des Victoria-Hotels von Llanberis! ...

In der Abendsonne saß ich gern auf dem grünen Rasenhügel vor dem Hotel. Vor mir die goldne Landschaft mit dem Wehn des Windes und der Frische des Wassers, die Tannen, die Seen, die Berge. Um diese Stunde ließ ich mir den Harfner von der Flur des Hauses kommen; er setzte sich unter den wilden Rosenstrauch, daß die Rosen ihm um Haupt und Harfe schwankten, und ich lag im thaufrischen Rasen. In seinen wild-herzlichen, träumerischen, neckischen Melodieen, die zwar nicht immer in ganz richtiger Harmoniefolge dahinrauschten, aber doch stets anregend blieben, rollte zuweilen der dumpfe Donner aus den entfernten Bergwerken. Schöne Britinnen suchten Bänke in der Nähe und horchten. Meine Gedanken aber zogen mit den Wolken gen Abend . . .

Die Melodieen, welche der Harfner am meisten spielte, waren das lieblich-frische Codiad yr Hedydd, welches ich einst zuerst hatte von Gwenni singen hören und das wehmüthige Ar hyd y Nos, welches den Walisern der liebste Ton zu sein schien, und während er spielte, sang ich im Geist und Maß der Melodien folgende Lieder still vor mich hin. ...

Ach, in der Nacht.

(Im Tone: Ar hyd y Nos.)

Stürme sausen, Wogen rauschen –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Hier am Strande will ich lauschen –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Wogen, Wogen auf und nieder, –

Sturmwind, deine dunklen Lieder

Wecken alle Leiden wieder –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Soll ich immer dein gedenken –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Schluchzend muß das Haupt ich senken –

Ach, in der Nacht! –

Hast mit Liebe mich gefangen.

Hast bethört mich mit Verlangen,

Hast bethört mich, bist gegangen –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Weh – nun pocht mir’s unter’m Herzen,

Ach, in der Nacht!

Pocht mir eine Welt von Schmerzen –

Ach, in der Nacht!

Keine Reue hilft, kein Denken –

Soll ich mich ins Meer versenken?

Soll ich dir das Dasein schenken . . . .

Ach, in der Nacht !

So giengen, mit Harfenspiel und Mittagssonnenduft die Tage von Llanberis dahin.

Where finally the village of Llanberis begins is where firs and beeches pleasantly band together; and I have found no other hotel situated more charmingly than the Victoria Hotel situated on its hill and surrounded by a garden and forest, with the remains of Dolbadarn Castle jutting out in a sombre fashion from behind. This sight is joined by the curious bustle, half poetic, half comical: beautiful English ladies with billowing veils and riding brave ponies prance forth from each mountain ravine – gentlemen, young and old, on their return from Snowdon, walking sticks in hand, bent stovepipe hats, tight trousers torn to shreds and their hands lacerated – the tour guides and errand boys – the donkeys and cobs – everything is topsy-turvy with laughter, grumbling, lowing and whinnying – and above all that sounds the harpist’s eternal jinglejangle as he sits between the coat racks in the hotel corridor. High above this tumultuous flurry, the fluttering English flag, the accessory of the Victoria Hotel in Llanberis, throws its shadow over the pale green lawn and the fir treetops at the foot of the mountain. ...

I enjoyed sitting in the evening sun on the green lawn in front of the hotel with the golden landscape, the billows of the wind and the mountain freshness, the firs, the lakes, the peaks before me. At this hour, I sent for the harpist to join me from the hotel corridor. He sat down underneath the wild rose bush so that the flowers nodded around his head and harp whilst I lay on the dewy lawn. Every now and then the rolling hollow thunder from the distant quarries joined his boisterously affectionate, wistful, whimsical melodies, which did not always flow in entirely correct harmony, but never failed to stimulate. Handsome British ladies were looking for nearby benches and listened attentively. My thoughts, however, joined the clouds and drifted with them into the evening . . .

The melodies played most frequently by the harpist were the prettily fresh ‘Codiad yr Hedydd’, which I first heard sung by Gwenni, and the whistful ‘Ar hyd y nos’, ostensibly the most favourite tune of the Welsh. And while he played on, I quietly sang the following after the spirit and measure of the melodies. ...

Oh, in the Night

(After the tune of ‘Ar hyd y nos’.)

Storms are waring, waves are roaring –

Oh, in the night!

On the beach I hear their soaring –

Oh, in the night!

Billows, billows rage eternal, –

Wistful songs the heart bedevil,

Stormwinds rousing gloom infernal –

Oh, in the night!

When I always think of you, dear –

Oh, in the night!

Sobs burst forth, your scorn I fear –

Oh, in the night! –

Tangled in the net of your smile,

You bewitched me with your guile,

Left me stranded in exile –

Oh, in the night!

Woe, my pounding heart is breaking,

Oh, in the night!

Leads me to a world of aching –

Oh, in the night!

No repentance helps, no thinking –

To the ocean floor I’m sinking.

Shall I face demise unblinking?

On, in the night!

Thus the days at Llanberis passed with harp song under a fragrant midday sun.

Ein Herbst in Wales, 1856

Julius Rodenberg (1831 – 1914)

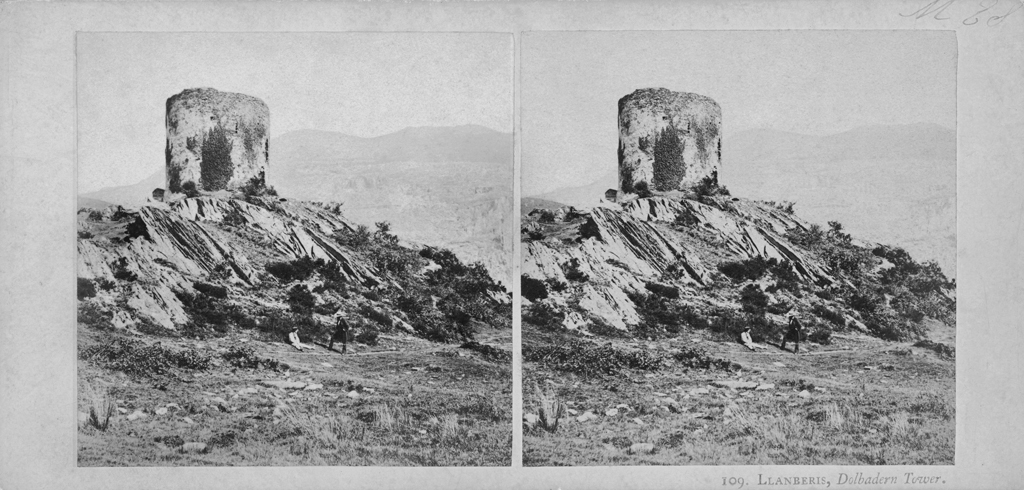

Zum Abschied bestieg ich noch einmal den Thurm von Dolbadarn, der einsam auf der Höhe zwischen beiden Seen steht. Es ist der einzige Rest des berühmten Schloßes, das noch vor der englischen Invasion, in grauen Jahrhunderten, erbaut ward, um den Mittelpunkt des walisischen Hochlandes zu schützen. Noch zu Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts ward Dolbadarn Schloß als eines der festesten in Nordwales erachtet. Nun ist es gebrochen und vom Wind, der hier über’s Gebirge schärfer streift, nackt gefegt. Lose Steine und hohes Unkraut füllen den Hof des Thurmes und seine Mauern zerbröckeln an der Erde, Staub mit Staub vermischend. Und doch ist es Wunder genug, daß dieser Thurm trotz der Wuth seiner einstigen Feinde und dem noch immer nagenden Zahne der Zeit sich so fest in seinen Trümmern gehalten hat. In diesem Thurme hat einst auch „der milde, der tapfre, der löwenherzige Owen, der Stolz, das Entzücken, der Abgott seiner Landsleute“ dreiundzwanzig Jahre geschmachtet als Gefangener seines Bruders Llewellyn, des letzten Fürsten von Wales, der ihn der Untreue gegen ihn beschuldigte.

Es war tiefe Nachmittagsstille. Die blauen Seen schillerten im Sonnenglanze, gegenüber der Rabenfels [der Schieferbruch Dinorwig] lag schon im Schatten. In den Mauern des Thurmes kletterten Dorfkinder in bloßen Füßchen mit flatternden Hemdchen und großen, dunklen Augen, wie Kobolde, herum. Auf einmal hörte ich unter mir ein Lied summen, welches mir wie ein Ton aus andren Welten klang. War es denn wirklich das? . . . Nein, nein – es konnte nicht sein – und doch! „Ein lust’ger Musikante – marschierte einst am Nil . . . o tempora! o mores!“ Das Lied der deutschen Studenten hier in Dolbadarn-Castle, an den Seen von Llanberis. . . . Ich ward seltsam ergriffen, und als es zum Schluß kam, da stimmte ich von oben ein: „Gelobet seist du jederzeit, Frau Musika!“ Sogleich erhoben sich unten zwei junge Männer, die unter einem Felsvorsprung im Grase gelegen hatten und Einer von ihnen rief mir ein burschikoses „Guten Morgen!“ herauf. Obgleich ich dem Accent anhörte, daß ich zu voreilig gehofft hatte, Landsleute zu finden, so war mir doch der Zufall angenehm, der mir einen jungen Mann zuführte, welcher – wie er mir sagte – in München gewesen war, um [Justus von] Liebig zu hören, und dann auch einen Sommer in Heidelberg sehr glücklich verlebt hatte. Der Andre war ein Stockengländer und verstand keine Sylbe Deutsch. Wie gesellten uns freundlich zueinander und da es sich ergab, daß wir eine Strecke Weges gemeinschaftlich machen könnten, so beschlossen wir in der Abenddämmerung abzureisen.

As a farewell, I once more climbed the tower of Dolbadarn, which stands alone on the hill between the two lakes. It is the sole remnant of the famous castle which had been built in the centuries of grey antiquity, even before the English invasion, in order to protect the centre of the Welsh highlands. Even at the end of the thirteenth century, Dolbadarn Castle was regarded as one of the strongest in north Wales. Now it is broken and swept naked by the wind, which blows much stronger here in the mountains. Loose stones and tall weeds fill the yard of the tower and its walls crumble near the ground, mingling dust with dust. And yet it is enough of a miracle that this tower, despite the fury of its former enemies and the gnawing ravages of time, has survived so strong in its ruined state. Here in this tower, ‘the mild, the brave, the lionhearted Owen, the pride, the delight, the idol of his fellow countrymen’ once languished for twenty-three years as the prisoner of his brother Llewelyn, the last Prince of Wales, who accused him of treason.

It was the deep silence of the afternoon. The blue lakes glistened in the sun and on the opposite side, the Raven Rock [Dinorwic Slate Quarry] lay in shadow already. Barefooted village children with fluttering shirts and large, dark goblin eyes were clambered around the tower walls. Suddenly I heard a song being hummed below me which sounded otherworldly. Was it really … ? No, no – it couldn’t – but yet! ‘Ein lust’ger Musikante – marschierte einst am Nil . . . o tempora! o mores!‘ (A merry musician once marched along the Nile . . . o tempora! o mores!) The song of German university students sounding here in Dolbadarn Castle, by the lakes of Llanberis. . . . I was strangely overcome and when it neared its end, I joined in the song from my location above, ‘Gelobet seist du jederzeit, Frau Musika!’ (Praise to you for ever more, Lady Music!) At once, two young men got up who had lain in the grass under a rock ledge and one of them hailed me with a boyish ‘Guten Morgen!’ Although I could tell from the accent that I had hoped too soon to meet with fellow countrymen, I nevertheless enjoyed the pleasant coincidence as it acquainted me with a young man who, as he told me, had been in Munich in order to hear [Justus von] Liebig and then also spent a happy summer in Heidelberg. The other one was a thorough Englishman and did not understand a single syllable of German. We mingled amicably and as it turned out that we could travel part of the way in each other’s’ company, we decided to depart together in the evening twilight.