Llanover Hall - Overview

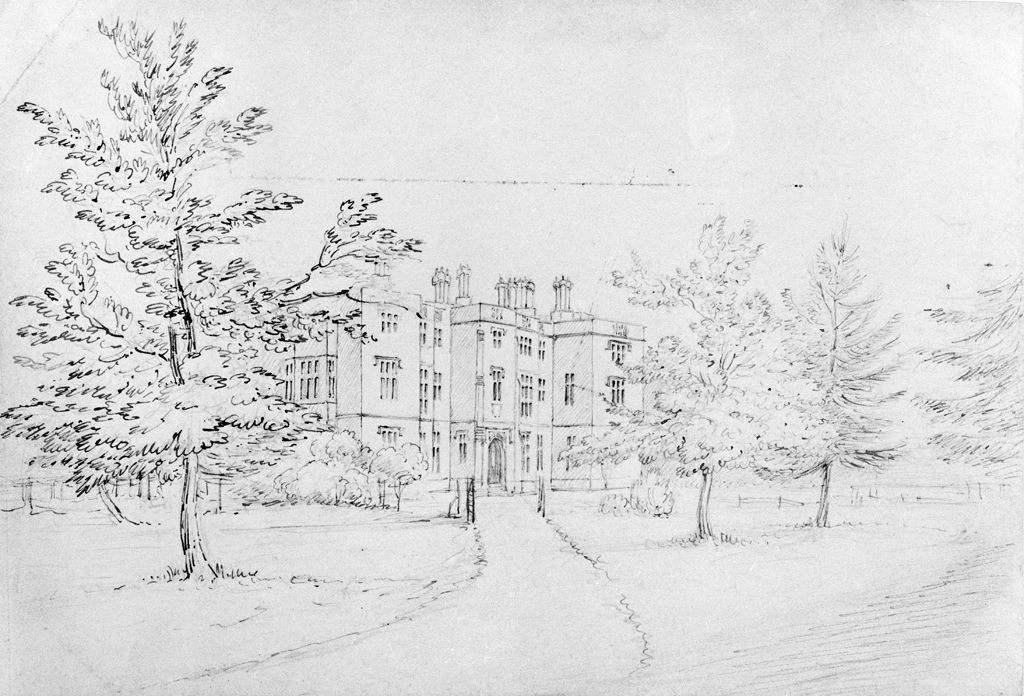

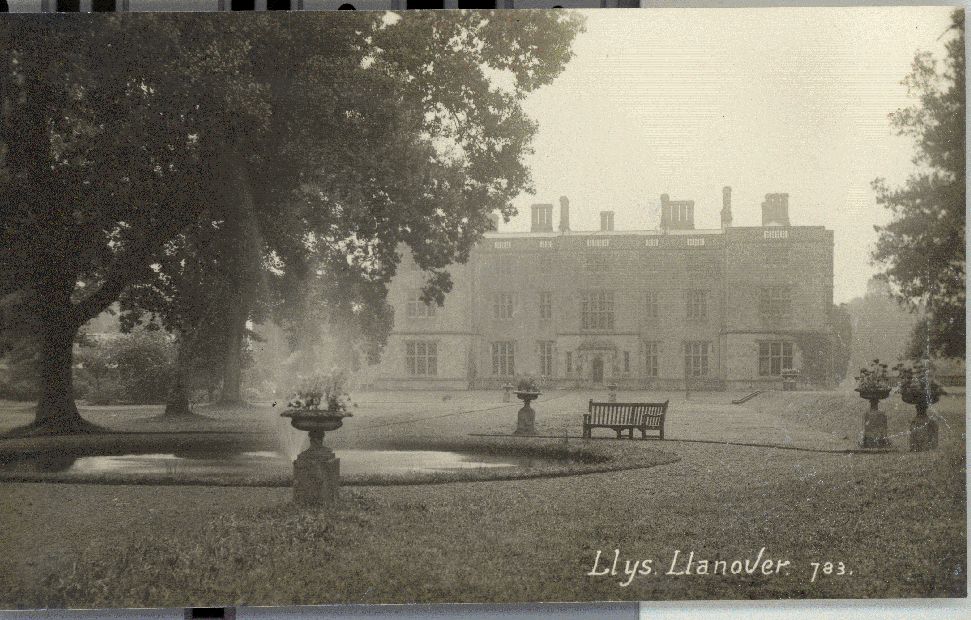

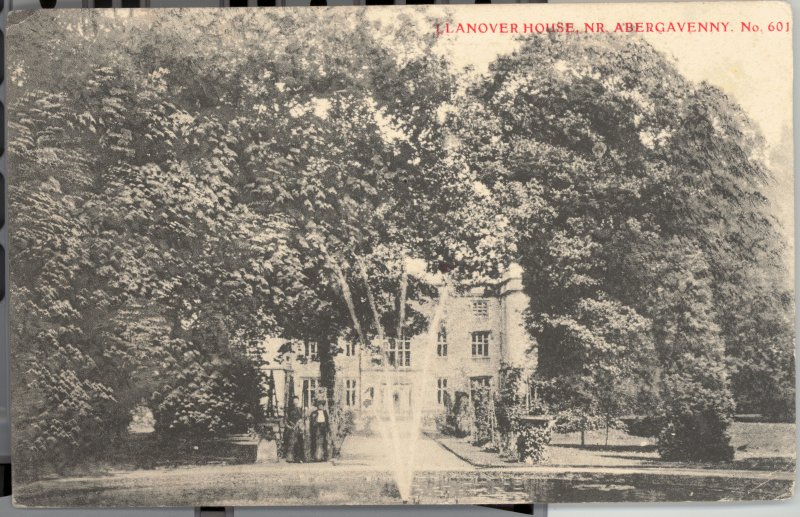

Llanover Hall holds a special place in the modern history of the revival of Welsh-language culture and literature. The mansion was a comparatively recent addition to the list of Welsh country houses, commissioned by Benjamin and Augusta Hall, Lord and Lady Llanover in the year 1828, and deigned by Thomas Hopper.

Benjamin Hall (1802–1867) was a wealthy civil engineer, MP and social reformer from Abergavenny. As he was responsible for overseeing the later phases of rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament, it is thought that ‘Big Ben’, the large bell in the clock tower that was installed under his supervision, was nicknamed after him. In 1823, he married Augusta, neé Waddington, (1802–1896) from nearby Abercarn.

Lady Llanover’s chief interests were the study of Welsh history, language and literature. She adopted the bardic name Gwenynen Gwent (the Bee of Gwent) and as a patron of the arts, she engaged a series of domestic harpists to work at her house and, further, encouraged the revival of country fashion worn by the peasantry in different parts of Wales. So fond was she of the various locally produced dresses that she took to wearing a more gentrified version during various cultural celebrations and festivities, and it may be claimed that Lady Llanover created the ‘national costume’ of Wales. (As Benjamin Hall did not quite share his wife’s penchant for dressing in country fashion, there is no male equivalent to the women’s costume.)

In addition, Lady Llanover was a collector of manuscripts and established the annual Cymreigyddion Y Fenni, a local eisteddfod to which she invited many international guests who shared her fondness of Welsh poetry and music. She was a patron of the Welsh Manuscripts society, funded the compilation of a Welsh dictionary and was instrumental in the founding of Y Gymraes, the first Welsh language periodical for women. Over the years, prominent guests included her German brother-in-law, the diplomat Christian Carl von Bunsen, as well as Théodore Claude Henri, vicomte Hersart de la Villemarqué, from Brittany who was initiated as a bard into the Gorsedd.

Llanover Hall, renamed to Llanover House, was largely demolished in 1936, but the surviving range remains a private home with a large garden and park. The owners frequently open the doors to the general public to enjoy the carefully maintained, 200-year old, landscape garden that had been commissioned by its first owners, Benjamin and Augusta, as well as continue the tradition of tree-planting themselves.

Accounts of Travel

Christian Carl Josias Freiherr von Bunsen: aus seinen Briefen und nach eigener Erinnerung geschildert von seiner Witwe, 1839

Carl Josias von Bunsen (1791 – 1860)

Am 29. September [1839], Sonnabends; trafen wir in Llanover ein. Wie ward mir; als ich am nächsten Morgen, bei schönem Sonnenschein und milder Luft, Gärten und Felder durchschweifte, wo Fanny ihre Kindheit und Jugend verlebt hatte. Der schöne muntere Bach, das friedliche Haus, das Glockengeläute rings um mich, und dann, die Landschaft bekränzend, die schönen Hügel. So war ich denn wieder einmal in einem älterlichen Hause, nachdem ich das angeborene vor gerade 30 Jahren verlassen, und im März 1816 zum letzten mal in ihm, unter seinem Strohdache geschlafen, und den Segen der Aeltern empfangen, die ich nie wiedersehen sollte! Ich war den ganzen Tag, soweit ich ihn nicht in der Kirche zubrachte, immer zwischen den lieblichen Feldern und besonders dem Garten, und dann dem Inneren, wo Frau und Kinder um die liebe anmuthige Großmutter umhersaßen und spielten. Das Herz und die Augen gingen mir über: der Krampf des lange verhaltenen Schmerzes löste sich in überwältigendes Dankgefühl auf.

On Saturday, 29 September [1839], we arrived at Llanover. How I was full of joy when in the beautiful sunshine and mild air of the following morning, I sauntered through gardens and fields where Fanny had spent her childhood and youth. The dear little brook, the peaceful house, the ringing of bells around me and then, encircling the landscape, the charming hills. Thus I found myself once more in an ancestral home after I had departed by own just thirty years ago and, in March 1816, had spent one final night under its straw roof and received the parents’ blessing, who I was destined never to see again! So far as I did not attend church, I remained the entire day in the lovely fields and especially in the garden and, later still, indoors where wife and children and the dear, gracious grandmother sat around and played. My heart and my eyes ran over: the paroxysm of the long suppressed pain melted into an overwhelming sense of gratitude.

Christian Carl Josias Freiherr von Bunsen: aus seinen Briefen und nach eigener Erinnerung geschildert von seiner Witwe, 1839

Carl Josias von Bunsen (1791 – 1860)

Die Tage der Ruhe dauerten nicht lange: das Cymreigyddionfest kam heran (9., 10. October [1839]), mit seiner poetischen Lebendigkeit, und kymrisch englischem Geräusch .... Lepsius’ Gegenwart verschönerte die Feier: des edeln Dr. Prichard Besuch war die schönste englische Zierde des Festes, obwol er allein der Unbemerkte blieb, der Einzige, welcher über die Kymri-Sprache wissenschaftlich-europäisch geschrieben hat! Einen eigenthümlichen Reiz gibt der Zusammenkunft das Gefühl des Volksthümlichen in dem Harfenspiele, und in dem Dichten und Singen aus dem Stegreife. Diesmal kam der merkwürdige Umftand hinzu, daß Graf Villemarqué aus der Bretagne gegenwärtig war, ein junger, achtbarer Forscher, der die Volkssagen und Lieder der Bretagne gefammelt hatte und zum Erstaunen der Kymri, und zu ihrem unbeschreiblichen Jubel sich, wenngleich nothdürftig, durch seine Muttersprache verständlich machen konnte, nach 1400jähriger Trennung. Alles Dies war ein wenngleich schwaches Abbild der hellenischen Spiele, und die Prosa dazu bildeten die Bälle der vornehmen Welt. Bei dem Festmahle der Gesellschaft mußte ich zum ersten mal öffentlich reden.

An der kymrischen Poesie gewann ich große Freude durch Turner’s geniale Forschung, die mich von der Echtheit der alten Lieder und mehrerer Triaden überzeugte. Ricci’s bescheidener Aufsatz und Jones Tegid’s, des Barden, lebendige Dichtungen zeigten mir das Eigenthümliche der alten Cimbern, mitten in der englischen Civilisation und in dem umschaffenden Gebiete des Christenthums. Nur mit der Sprache selbst konnte ich mich, jenseit der grammatischen Theilnahme, nicht befreunden. Der Schulmeister des Ortes, der auf einer lateinischen Schule gelehrt war, dann 20 Jahre Englisch und Britisch in der Dorfschule mit den Kindern getrieben hatte, konnte mir beim Lesen des Evangeliums nichts erklären, sobald die Wortstellung in den beiden Uebersetzungen verschieden war. Ob die Kymren vorzugsweise blond oder braun seien, konnte ich, trotz aller Bemühungen, nicht mit Sicherheit ausmachen.

The days of calm did not last long: the Cymregyddionfest had arrived (9-10 October [1839]) with its poetic liveliness and Cymro-English noise …. Lepsius’s presence improved the celebrations; the noble Dr Prichard’s visit proved the handsomest English ornament of the fest, although he remained the sole unrecognised one, the only one who has written academically on the Cymric language in Europe! A particular charm is given to the gathering by the folkloristic touch of harp music and impromptu poetry and song. This time was further made noteworthy by the presence of Count Villemarqué from Brittany, a young, respectable researcher who had collected the folk tales and songs of Brittany and who, to the astonishment and indescribably joy of the Cymry, was able to communicate with them, albeit scantily, through his mother tongue even after 1400 years of separation. All this was a somewhat weak image of the Hellenic games, the prosaicness having been provided by the balls of respectable society. During the banquet I was obliged to speak publicly for the first time.

I found great pleasure in Cymric poetry thanks to Turner’s ingenious research which convinced me of the authenticity of the old songs and various triads. Ricci’s humble essay and the bard Jones Tegid’s lively verse showed me the traits of the old Cumbrians in the midst of English civilisation and the transforming domain of Christendom. Only with the language itself, outside the rules of grammar, I was unable to make friends. The local schoolmaster, who had received his education in a Latin school before teaching children the English and British languages in the village school for twenty years, was could not explain anything to me in my reading of the Gospel, as soon as the word order differed in the two translations. Whether the Cymry are predominantly blond or brunette, I could not say for certain, despite all my attempts.

"Voyage dans le pays de Galles", 1862

Alfred Erny (1838 – )

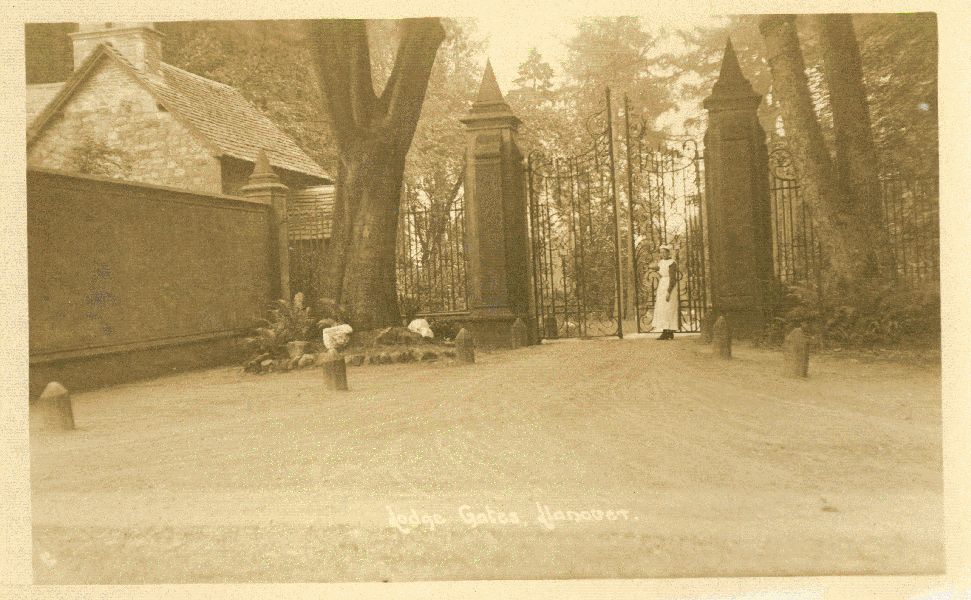

La principale entrée de Llanover (Porth Mawr), est la représentation exace de l’ancienne porte des Tudors, détruite il y a quelques années à Abergavenny. Sur le fronton est gravée une inscription galloise, que je cite pour son caractère d’antique hospitalité.

Qui es-tu voyageur?

Si tu es ami, du fond du cœur sois le bienvenu.

Si tu es étranger, l’hospitalité t’attend.

Si tu es ennemi, la bonté te retiendra.

En descendant de voiture, j’allai remercier lord et lady Llanover pour la gracieuse invitation qu’ils m’avaient faite de passer quelques jours au château. ...

La réception qu’on me fit fut aussi cordiale que gracieuse. Milady me conduisit immédiatement dans son jardin où je m’arrêtai devant un Rhododendron gigantesque de cent cinquante pieds de circonférence. Au milieu d’un petit bois, j’aperçus neuf fontaines provenant de leur sources aussi abondantes l’été que l’hiver, et qui ne tarissent jamais, même dans les plus chaudes saisons. Plus loin, en traversant le parc, nous arrivâmes au village de Llanover. Milady, qui s’occupe du bien-être de tous, était venue nous accompagner, M. Martin et moi. Elle s’arrêta dans plusieurs maisons, et donna à chacun de ses tenanciers des encouragements et de bonnes paroles. L’intérieur des fermes est remarquablement soigné, tous les meubles sont frottés; le foyer est en fer, les parquets luisants et polis rappellent la propreté des maisons hollandaises.

The main entrance to Llanover (Porth Mawr), is an exact copy of the former Tudor door that was destroyed a few years ago at Abergavenny. On the pediment a Welsh inscription is engraved; I shall cite it for what it says about ancient hospitality:

Who are you traveller?

If you are a friend, from the bottom of the heart, welcome.

If you are a stranger, hospitality awaits you.

If you are a foe, goodness will keep you here.

Alighting from the carriage, I went to thank Lord and Lady Llanover for their kind invitation to spend a few days at the manor. ... The welcome I received was as warm as it was kind. Milady immediately took me to the garden where I stopped in front of a gigantic rhododendron, one hundred and fifty feet in circumference. In the middle of a little woods, I saw nine springs flowing from their sources, just as full in summer as in winter, and that never dry up, even if the hottest of summers. Further on, across the grounds, we arrived at the village of Llanover. Milady, who takes care of everyone’s well-being, had come to accompany Mr Martin and myself. She stopped in many houses, giving each one of her tenants’ words of encouragement and kindness. The interiors of the farmhouses are remarkably well-kept, all the furniture has been scrubbed, the fireplace made of iron, and the shiny polished wooden floors are reminiscent of the cleanliness of Dutch houses.

"Voyage dans le pays de Galles", 1862

Alfred Erny (1838 – )

Une autre fois, nous allâmes visiter l’ancienne court de Llanover, c’est-à-dire l’endroit où habitait la famille Hall avant la construction du château, qui ne date que d’une trentaine d’années. La porte d’entrée, un couloir et un bel escalier sont en bois sculpté. Dans la salle, près du foyer je remarquai un vieux siège en bois où quatre peronnes peuvent s’asseoir: c’est là que se réunit la famille après le repas du soir, et c’est le moment que choisissent les vieillards pour conter les légendes de fées qu’affectionnent tans les Gallois. ... Le château élégant et spacieux possède une grande salle (ou hall) remarquable par la haute galerie où se placent les musiciens et les chanteurs, les dimanches et jours de fête. Une première bibliothèque, où se trouvent les portraits de Guillaume III et de Cromwell, fait suite à un magnifique salon orné de tableaux et de curiosités de toutes sortes: au-dessus d’un groupe de porcelaines on distingue le portrait de Nell Gwyn, une des favorites de Charles II.

Dans la deuxième bibliothèque, une tête vigoureuse, signée de Michel-Ange, attira mon attention. Un meuble très-curieux est un coffre en bois de chêne qui contient tous les manuscrits Gallois achetés par lady Llanover au fils d’Iolo Morganwg, le barde du Glamorgan; beaucoup de ces écrits datent du quinzième et seizième siècles et quelques-uns remontent même jusqu’au douzième.

Another time we went to visit the ancient Llanover court, the place where the Hall family resided before the construction of the manor, which is only some thirty years old. The entrance door, a corridor and a fine staircase are in sculpted wood. In the hall, near the fireplace, I noticed an old wooden chair on which four people can sit: this is where the family gathers after the evening meal, and this is the moment chosen by the elders to tell the fairy tales that are so dear to the Welsh. ... The elegant and spacious castle has a grand hall that is remarkable on account of the high gallery where musicians and singers perform on Sundays and holidays. A first library, housing portraits of William III and Cromwell, is connected to a magnificent drawing room decorated by paintings and all sorts of curiosities: hanging above a group of porcelain pieces is a portrait of Nell Gwyn, one of Charles II’s favourites.

In the second library, a head, signed Michael Angelo, caught my attention. A most fascinating piece of furniture is an oak chest that contains all the Welsh manuscripts that Lady Llanover bought from the son of Iolo Morganwg, the bard of Glamorgan; many of these texts date from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and some as far back as the twelfth.