Merthyr Tydfil - Overview

The area around Merthyr Tydfil shows evidence of small scale settlement from the prehistoric periods onwards, and the name originates in the tale of the martyred Saint Tydfil, one of the many daughters of the fourth-century ruler Brychan Brycheiniog. Until the mid-eighteenth century, the valley was sparsely populated with farming and the rearing of livestock forming the main economy, though a small village had formed on the site of the modern day town.

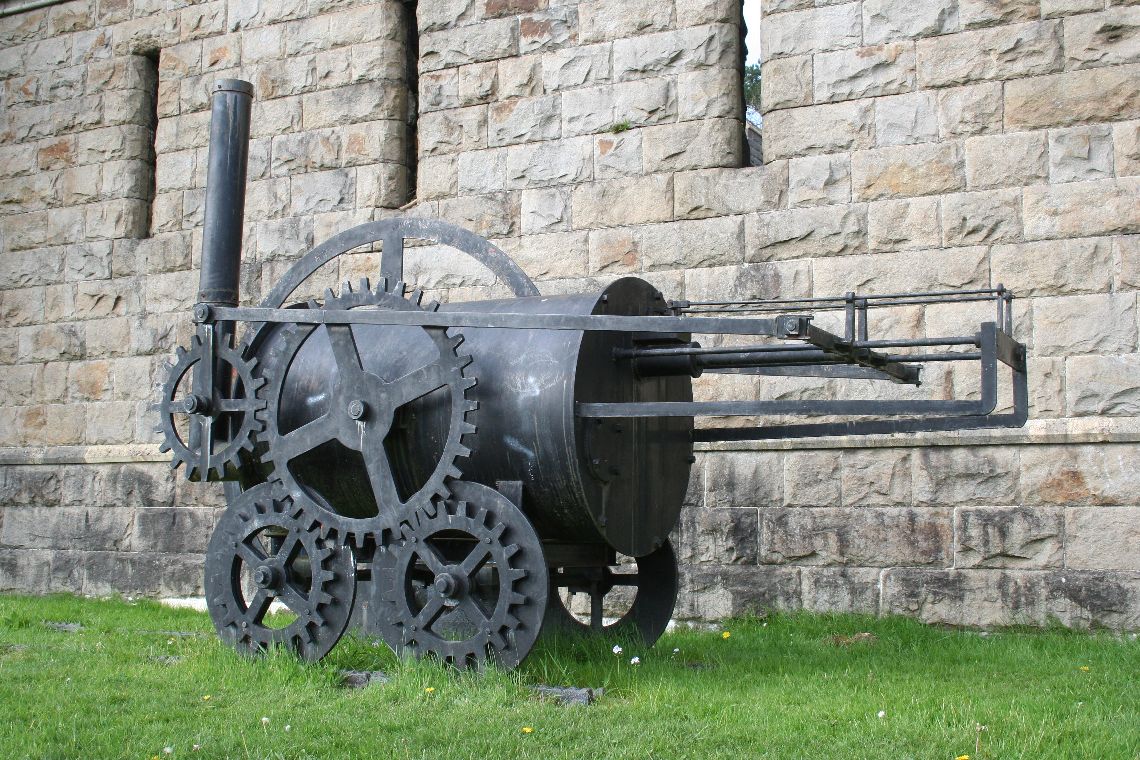

In the early eighteenth century abundant deposits of iron ore, coal and limestone were discovered, making it an ideal location for the relatively new ironwork industry that was leading Britain Industrial Revolution.

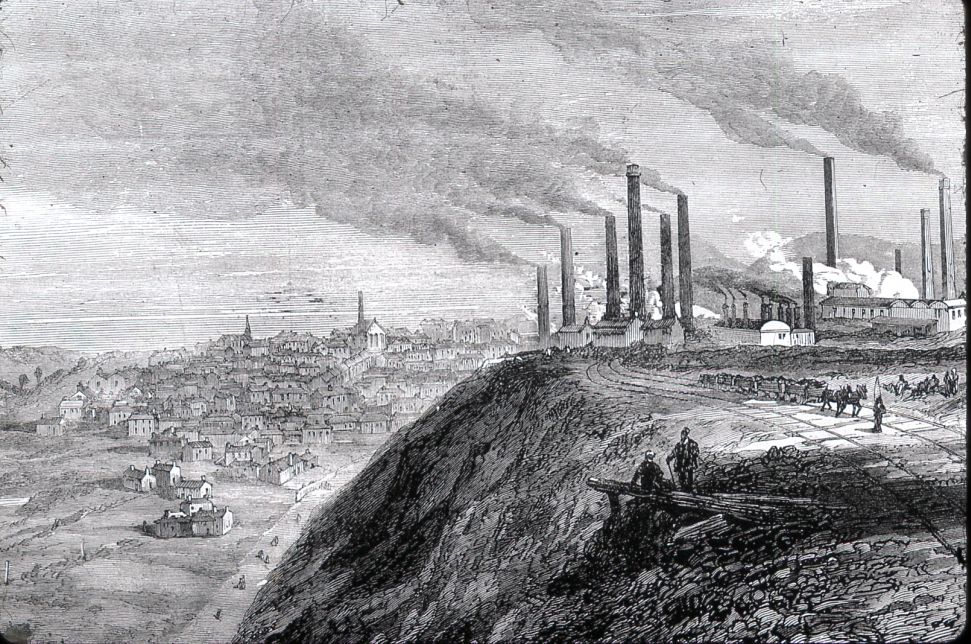

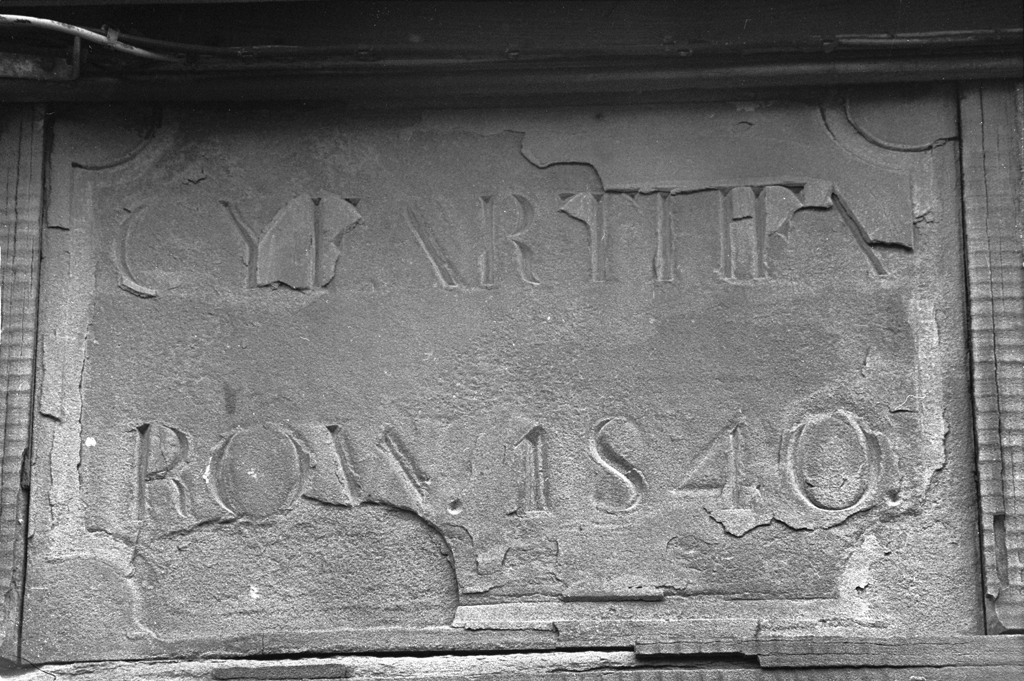

In 1759, the first major ironworks, Dowlais, was founded. Other works, including Plymouth, Cyfarthfa and Penydarren, followed in quick succession and Merthyr Tydfil changed beyond recognition. Under the ownership of John Josiah Guest between 1807 and 1852, Dowlais rose to international fame as the largest ironworks worldwide employing 8,800 workers and producing 88,000 tonnes of iron a year. By 1820, Merthyr was producing 40 per cent of Britain iron exports, while in the second half of the nineteenth century, many of the works converted to the production of steel.

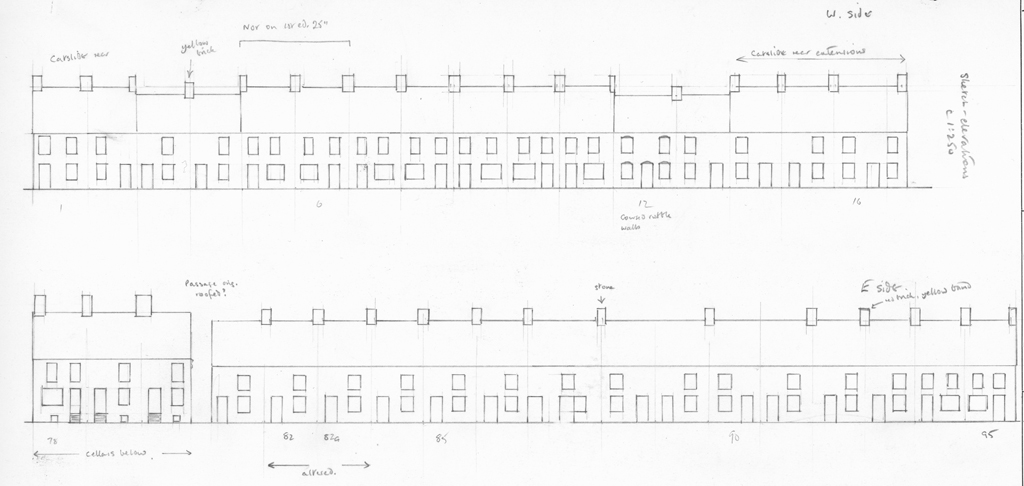

As a result of the rapid expansion of industrial production and mining activities, the population of Merthyr Tydfil increased dramatically. The 1801 census recorded 7,000 people in the parish – by 1910 Merthyr Tydfil had almost 90,000 inhabitants.

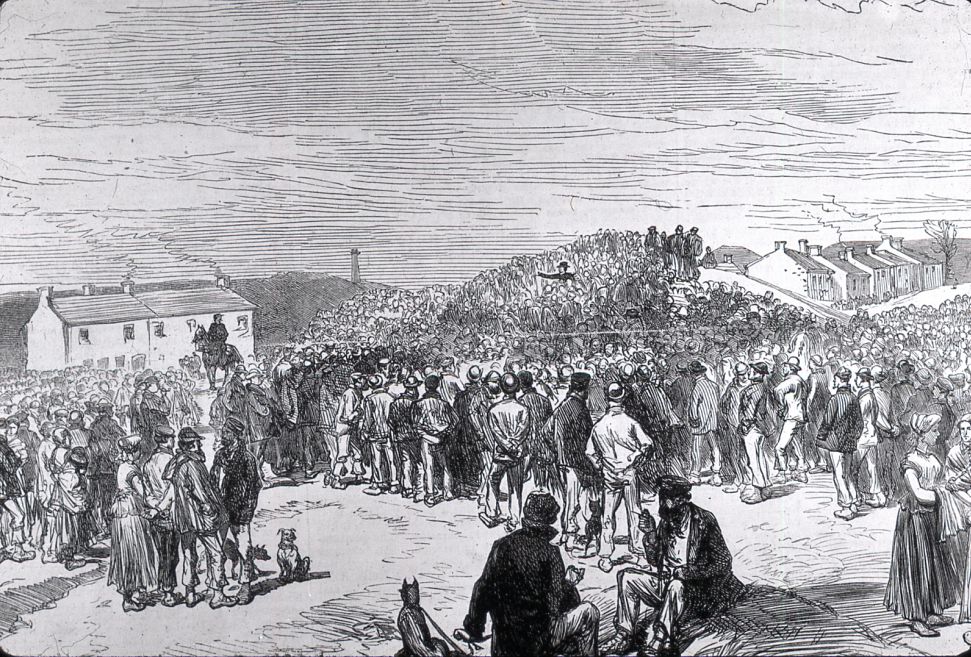

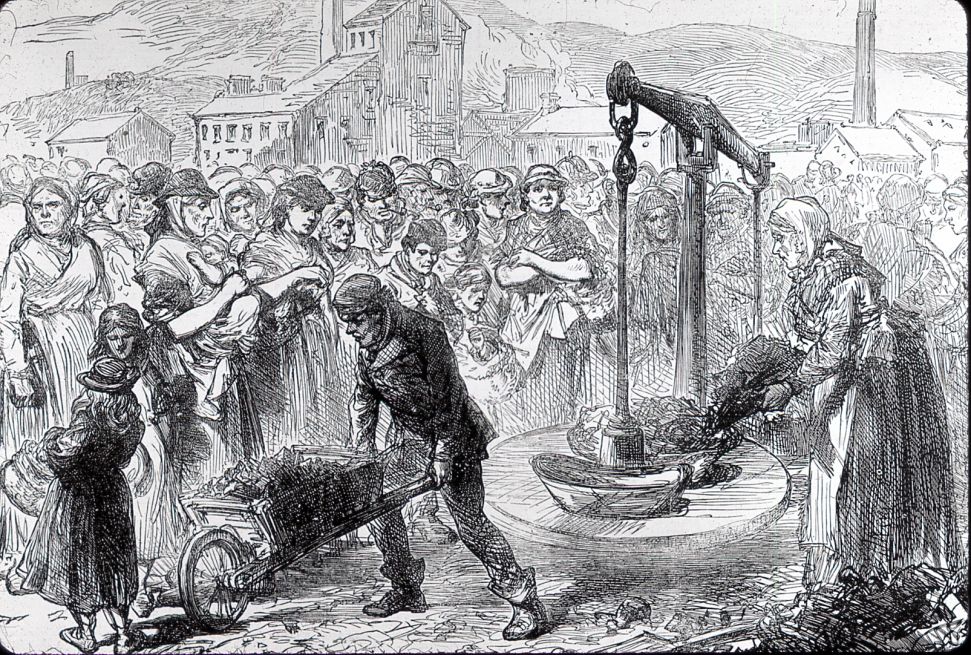

Due to crammed living conditions in the terraces of workers housing and the lack of proper sanitation, disease was rife and life expectancy low. The low wages of the industrial workforce, poor working conditions and the implementation of the ‘truck system’ by the iron masters, in which workers were not payed real money, but vouchers and tokens valid only in their masters’ own shops, contributed to ongoing social unrest. In 1831 the increasing tension came to a head, triggering the Merthyr Rising. For the first time, workers united under the red flag and effectively took control of the town for four days. The situation spun out of control as soldiers were moved in to suppress the movement. One of the leaders, Dic Penderyn (Richard Lewis) was arrested and hanged while others were sentenced to transportation to Australia.

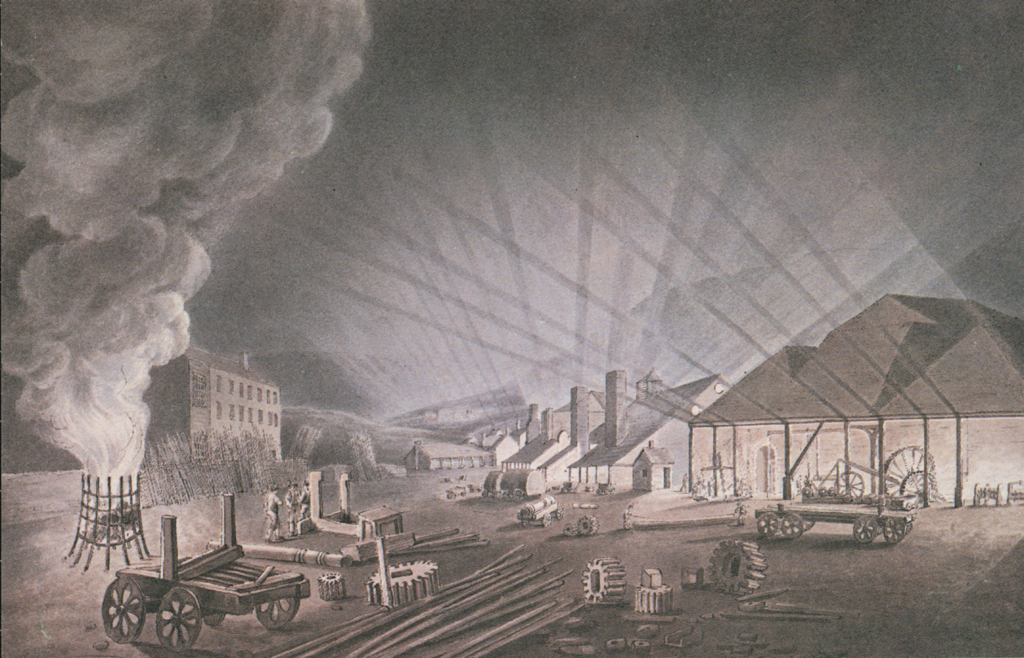

Although lacking the picturesque beauty of medieval ruins or the grandeur of the mountain landscapes of Snowdonia, Merthyr Tydfil drew a steady stream of visitors from mainland Europe. During the day, the travellers carefully studied the cutting edge production methods in the numerous factories, while at night they stared in wonder at the ‘hell-fire spectacle’ of the furnaces illuminating the entire valley.

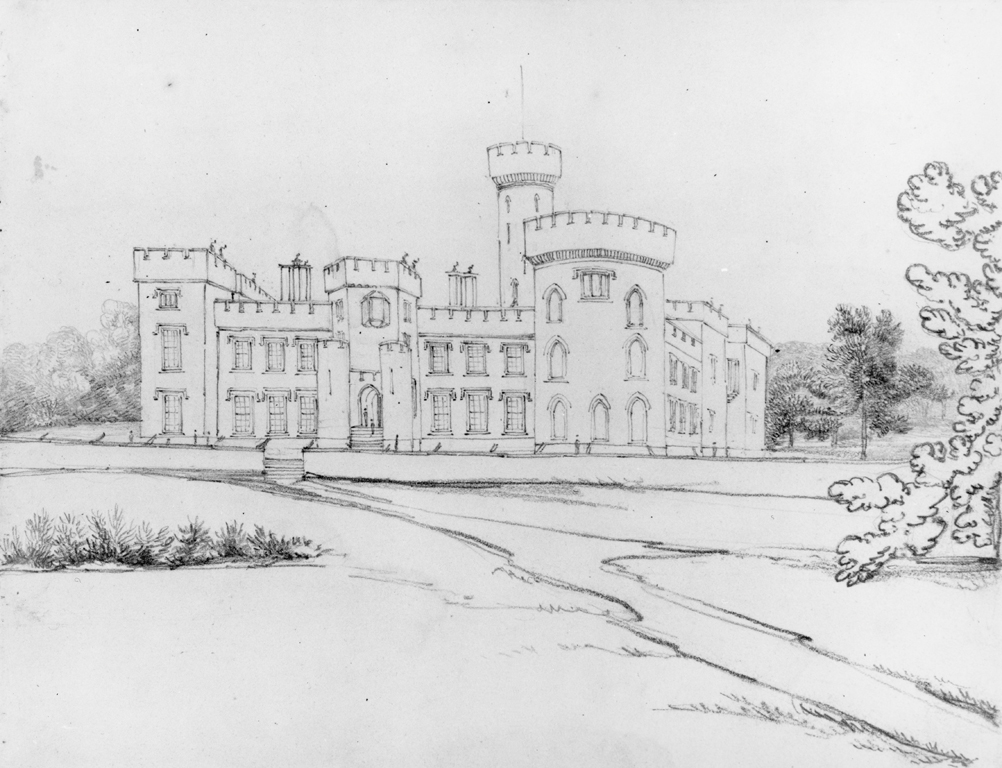

Thanks to its international industrial reputation, declining steel and iron production in the mid twentieth century was replaced by manufacturing industries. Today, major land restoration projects are under way to enhance landscapes formed by largescale coal mining and metallurgic production, while museums, such as the Cyfarthfa Castle Museum, keep Merthyr Tydfil’s industrial heritage alive.

Accounts of Travel

England und Schottland im Jahre 1844, 1844

Carl Gustav Carus (1789 – 1869)

Näher hierher nach Merthyr Tydvil zu, wurden die Eisenwerke immer zahlreicher, überall an den Bergen Hüttenwerke und Halden, kleinere Eisenbahnen und Kanäle, alles für den Transport des Eisens. In einem Thale sah man unten einen Kanal und die Eisenbahn für Dampfzüge, weiter oben zog sich unsre Fahrstraße hin, und noch höher oben war eine zweite Eisenbahn für Pferde zum Besten des Grubentransports und der Arbeiter. – Wir trafen weiterhin auf solcher Eisenbahn einmal ganz lange Züge von schwarzen Kohlenwagen und andern, mit schwarz und braunbestäubten Arbeitern besetzten Waggons! – es gab einen seltsamen Anblick! – Und welche Berge von Schlacken schichten sich hier auf! – Die Ausbeute dieser Gebirge an Eisen muß ganz ungeheuer seyn! –

Der Menschenschlag verändert sich hier ganz und wird unschön; die Frauen tragen runde Männerhüte oder schwarze Strohkappen auf den Köpfen, und dabei eine wunderliche ungeschickte Kleidung: ich wurde ein paar Mal an die Frau aus Unalaschka in Cooks Reisen erinnert.

Alle andern Betrachtungen schwinden jedoch, sobald einem die Größe und der Umfang der Eisenwerke hier am Orte selbst deutlich wird. Schon das erste wo sechs Hoheöfen brannten, gewährte einen wundersamen Anblick. Über den flammenden Kegeln der Hoheöfen zitterte die erhitzte Luft und machte, daß die Contoure der dahinter aufsteigenden Schlackenberge Wellen schlugen. – Mir fielen bei diesen Schlackenbergen höhere Vulkane ein, und die Hoheöfen erinnerten an kleinere brennende Auswurfskegel an deren Seiten. – Noch viel mächtiger aber wurden die Eindrücke, als wir weiter hinaufstiegen und die großen Eisenwerke von Sir John Guest u. Comp. in Augenschein nahmen. Man konnte sich hier in die glühende Stadt des Dis im Dante versetzt glauben! – Man führte uns zuerst nach den Gruben, deren ungeheure Ausbeute an Kohlen und Eisen zugleich, alles dieses erst möglich macht. – Es kann von der Größe der Production einen Begriff geben, wenn man hört daß nur in den letzten fünf Wochen 36.000 Tonnen Kohlen heraufgefördert worden waren; zuweilen 1500 in einem Tage; und alle diese Kohlen werden auch im Werke selbst verbraucht. Gleich daneben werden dann zugleich auch ähnliche Mengen von Eisenstein heraufgebracht. – Freilich sind die Arbeitskosten auch ungeheuer! – Die Werke haben circa 6000 Arbeiter täglich, und das Arbeitslohn mit sonstigen Unterhaltungskosten steigt dann monatlich gewöhnlich bis zu 26.000 Pfund Sterling! ...

Es interessirte mich sehr an der weiten doppelten Schachtöffnung zu stehen und zuzusehen, wie – bewegt durch eine nahe gestellte Dampfmaschine und geleitet durch eine unterirdische Eisenbahn – auf einer Seite die Reihe leerer Wagen und eine Anzahl Arbeiter mit Grubenlichtern in den Berg hineingefahren wurdem, während auf der anderen Seite bald darauf eine andre Reihe Wagen theils mit Kohlen theils mit Eisen gefüllt, und mit andern Arbeitern besetzt heruaskamen. – Die Sorglosigkeit mit welcher auch hierbei verfahren wurde, konnte zeigen was tägliches Ausssetzen an Gefahr über den Menschen vermag. Viele dieser Arbeiter kamen aus dem schief aufsteigenden Schacht herauf – ganz frei und aufrecht auf demselben Drahtseile wie Equilibristen stehend, welches mit Schnelligkeit der Dampfkraft die Wagenreihe aus dem Berge hervorzog. Es hätte nur einer Seitenschwenkung im Dunkel der Höhlen bedurft, und der Mann stürtze herab und wäre von dem nachfolgenden Wagenzuge zerquetscht worden. – Indeß ist diese Sorglosigkeit nicht nur in diesen Parforcetouren sichtbar, sondern auf gleiche Weise wird auch im Innern verfahren. Daher namentlich, trotz Davy’s Sicherheitslaterne, häufiges Entzünden schlagender Wetter. Wir erfuhren daß erst heute früh im Schacht drei Arbeiter auf diese Weise durch Gasentzündung verbrannt waren.

As we approached Merthyr Tydvil, the iron-works became more numerous; we saw everywhere smelting-houses and forges, little railways and canals for the conveyance of the iron from one place to another. In one valley we saw below a canal, and a railway for locomotive engines; higher up, the road upon which we were, and still higher, a tram-road for the conveyance of materials and workmen belonging to the mines. We met on another occasion, on such a tram-road, along train of black coal-waggons, and others covered with workmen black and brown with dust – a curious sight! And what mountains of dross were piled up. Certainly, the quantity of iron produced in these mountains must be enormous.

The race of people which we found here, is very much the reverse of handsome; the women wear men’s hats on their heads, or black straw hats, and along with this, a very awkward, ungraceful dress. I was reminded once or twice of the women of Unalaska, mentioned in ‘Cook’s Voyages’.

All other considerations however vanish, when one comes to understand the size and extent of the iron-works themselves. The first we visited, in which six blast furnaces were at work, presented an extraordinary sight. Above the flaming chimneys of the blast furnaces the heated air trembled, and made the outlines of the mountains of dross behind them appear wavy. I could not help imagining these mountains of dross to be volcanoes, and the blast furnaces little burning craters on the sides of the larger ones. The impression produced was a much more powerful one, when we went further and took a view of the great iron-works belonging to Sir John Guest and Company. One could easily have believed oneself transferred to the blazing city of Dis, mentioned by Dante! We were first conducted to the mines, the immense quantity of coal and iron produced by which rendered all this possible. Some idea of this quantity may be obtained from the fact that in the last five weeks 36,000 tons of coal have been dug out, sometimes 1500 tons in a day, and that all these coals are employed in the works. Close to this mine is that from which a similar quantity of ironstone is produced. The cost, of course, is enormous! The works employ about 6000 work-people daily, and the wages of these workmen, with food, &c., amounts to about 26,000l. a month! ...

I was also much interested in standing at the double entrance to the shaft, and observing how, set in motion by a steam-engine, and conducted along a subterraneous railway, on the one side a row of empty waggons, and a number of workmen, with miners’ lamps, were conveyed into the mountains; whilst, on the other side, shortly after, a number of waggons loaded with ironstone and coal, and with other workmen, came out from the cavern. The carelessness with which the workmen acted, sufficed to show the influence of daily exposure to danger. Several of the men came out of the sloping shaft, quite without holding, and standing upright upon the rope which drew the waggons out of the centre of the mountain. The slightest inclination to either side, in the darkness of the cavern, would have been sufficient to precipitate the man from his position, and he would have been crushed to pieces by the next waggon. This carelessness is, however, not merely manifested in such exhibitions of skill, but is even shown in a similar manner in the interior. Hence, notwithstanding Davy’s safety lamp, accidents are continually occurring from cold damp. Only this morning three workmen were killed in this manner, in one of the workings.

(The King of Saxony’s Journey Through England and Scotland in the Year 1844. Trans. S.C Davison. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846)

Dawlais Works, die Eisen- und Schienen-Walzwerke des Hauses John Guest, in London, 1844

Carl Klocke ( – )

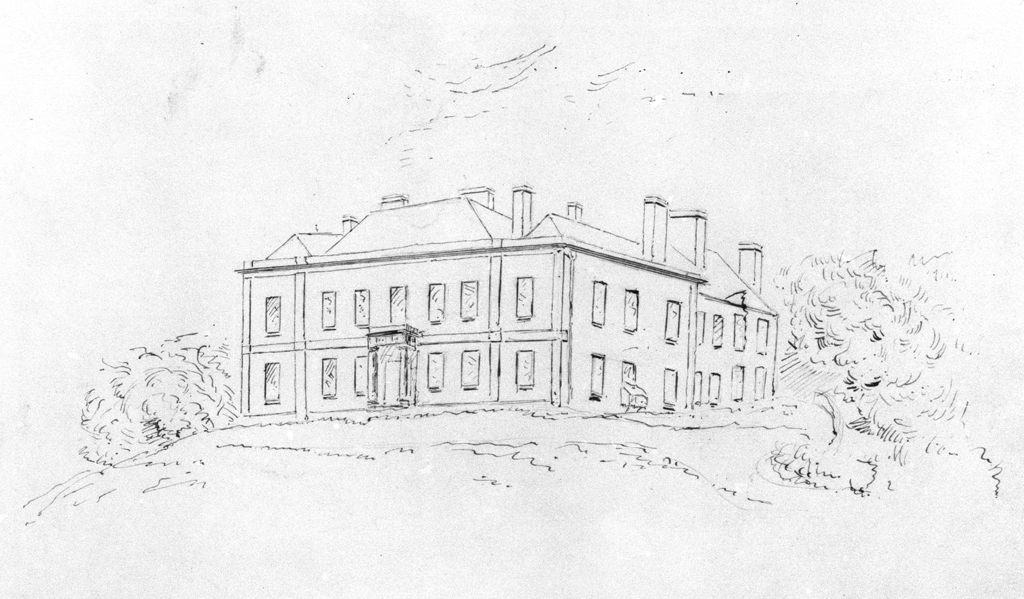

Die Erwartung wird mehr und mehr gespannt, und oben, wo das Thal sich schließt und die Berge zusammenrücken, liegen Dawlais-Works, links an und auf dem Berge der Flecken Dawlais mit einigen hervortretenden kleinen Kirchen und Kapellen. Wie wir uns nähern, macht unser Kutscher uns aufmerksam auf eine derselben, als Sir John’s Kapelle, da Sir John Guest allein dieselbe bauen ließ, auf Sir John’s Markthalle und auf dessen Wohnhaus, unmittelbar über den Werken; dann auf den Garten für Sir John’s Pferden und drei Spazierreiter, die uns begegnen, sind nicht minder Sir John’s Chirurgen. Unser Omnibus hält vor einem kleinen reinlichen Gasthofe, in der Hauptstraße von Dawlais und wir sind am Ziele. Man hört die Dampfmaschinen arbeiten, die Gebläse brausen; aus den Fenstern der obern Etage sieht man die Flammen aus den Hochöfen flackern, die daher auch die Schlafzimer in der Nacht, wie eine ganz nahe Feuersbrunst, erleuchten und es bedarf einer kleinen Gewöhnung, um dabei ruhig einzuschlafen. ...

Man würde aber Dawlais nicht gesehen haben, wenn man nicht auch in späterer Abendstunde einen Spaziergang nach den umliegendend Höhen gemacht hätte. Sir John Guest kann seinen Gästen zu Dawlais jeden Abend Illumination und Feuerwerk anbieten, wogegen die berühmten Feuerwerke in den Surrey-Gärten in London – wo man den Brand von London im Jahre 1666 großartig genug darstellt – ein Kinderspiel sind. Die Hochöfen gleichen einer brennenden Stadt; die tiefer liegenden Feuer und Essen, mit den beleuchteten hohen Schornsteinen der Dampfmaschinen, einer eben niedergebrannten Stadt. Die noch nicht ausgekühlten Schlacken leuchten am Abende wie glühende Lava; in mächtigen Haufen aufgeschüttet, hie und da an der äußersten Kante ziemlich hoher Berge, ziehen sie sich gleich glühenden Lavaströmen ins Thal hinab. ... Dazu muss man aber nicht an einem Sonnabende oder Sonntage nach Dawlais kommen, denn Sir John Guest sagt nicht nur mit Nelson: „that he expects every man to do his duty,“ sondern er fügt auch hinzu: „that he likes to see every body enjoy his Sunday“, das heißt, er verlangt wohl, daß im Laufe der Woche Jeder seine Schuldigkeit thue, aber er wünscht auch, daß alsdann jeder seinen Sonntag genieße.

Daher erlöschen am Sonnabend Nachmittage in noch ziemlich früher Stunde – mit Ausnahme der Hochöfen, welche natürlich keine Unterbrechung erleiden können – alle übrigen Feuer und die Dampfmschinen hören auf zu stöhnen, aus den nahen und entferntern Werken strömen die Arbeiter und Gespanne zur Stadt.

Anticipation mounts and, finally, at the end of the valley, where the mountains close in, lie the Dowlais works, and to the left and across the top of the peak is the hamlet Dowlais with a few protruding small churches and chapels. As we approach the place, our coachman identifies one of them as Sir John’s chapel, for it was Sir John Guest himself who had it built, then there is Sir John’s market hall and his estate situated directly above the works; next, the garden for Sir John’s horses and the three horsemen on an outing who are passing us, are none other than Sir John’s surgeons. Our omnibus terminates in front of a small, neat guesthouse on the High Street of Dowlais and we are finally at the end of our journey. One can hear the steam engines at work and the roar of the bellows; from the windows on the upper storey one can see the flickering flames of the blast furnaces which, like a nearby fire storm, then illuminate the bedrooms at night and it takes some adjustment in order to fall peacefully asleep. ...

Yet, one would not have seen Dowlais properly without having gone for a walk over the surrounding heights during the late evening hours. At Dowlais, Sir John can offer his guests illuminations and fireworks every evening. By comparison, the famous fireworks of the Surrey Gardens in London (where they fabulously depict the Great Fire of London in the year 1666) are but child’s play. The blast furnaces resemble a burning city, whereas further below, the fires and forges, together with the illuminated tall chimney stacks of the steam engines, looks like a city which has just recently burnt down. In the evening light, the not quite extinguished slags gleam like glowing lava; raised up to towering heaps, here and there on the outermost edge of tall mountains, they flow to the valley like burning streams of lava. ... However, to witness one such sight, one must never come to Dowlais on a Saturday or Sunday, because Sir John Guest not only quotes Nelson in saying ‘that he expects every man to do his duty’, but he also adds ‘that he likes to see every man enjoy his Sunday’.

It is for that reason that – except for the blast furnaces which, naturally, cannot suffer any disruption – at a fairly early hour each Saturday afternoon, all other fires and steam engines cease their groaning, and the workers and drawn carts swarm from the near and far factories towards town.

"Une Visite aux Grandes Usines du Pays de Galles", 1862

Louis Simonin (1830 – 1886)

Ici tout prenait un ton triste, sale et misérable, comme si le charbon et le fer ne pouvaient aller qu’avec la boue et la malpropreté, celle qu’ils créent autour des mines et des usines, comme celle dans laquelle vivent, au moins dans le pays de Galles, les ouvriers attachés à leur exploitation. A Merthyr, la ville elle-même offre un aspect triste et rebutant. Les rues ne sont ni balayées, ni lavées; la crotte et l’ordure s’yn entassent; une poussière noire, produite par la fumée et le charbon, s’étend sur les façades des édifices et jusque sur les vêtements et la figure des habitants. Dans un tel milieu, le laisser aller, la négligence, puis la misère prennent vite droit de cité, et voilà comment s’explique peut-être le spectacle navrant dont une portion de la classe ouvrière de Merthyr nour rendit trop souvent témoins.

L’usine de Cyfarthfa, autour de laquelle s’étala pour la première fois devant nous la misère galloise, est une des plus grandes usines à fer du pays de Galles, et partant de toute l’Angleterre. C’est la plus importante de Merthyr Tydvil, après celle de Dowlais. Celle-ci a dix-sept hauts fourneaux pour traiter le minerai de fer et le transformer en fonte, près de cent soixante fours à réverbère pour transformer la fonte en fer malléable, et un nombre proportionné de trains de laminoirs et de marteau-pilons pour achever le traitement métallurgique de fer.

La consistance de Cyfarthfa est moins importante que celle de Dowlais. L’usine n’a que sept hauts fourneaux, quatre-vint-quatre fours à puddler, et n’occupe guère que six à sept mille ouvriers; mais c’est encore un assez beau lot.

De toutes ces vastes usines, le métal entré à l’état de minerai, sort à l’état de fonte moulée, mais surtout à l’état de fer marchand, en barres ou en verges, rond ou carré, en feuilles, lanières, rubans, enfin à l’état de rails. Jamais les usines ne chôment ni de jour ni de nuit. Les hauts fourneaux, géants des foyers métallurgiques, hauts de quinze mètres, peuvent produire jusqu’à quarante mille kilogrammes de fonte par vingt-quatre heures.

Everything about this place seemed sad, unclean and destitute, as if coal and iron were inseparable from mud and dirt, the dirt that they [coal and iron] make all around the mines and factories just as much as the dirt in which the workers, Welsh workers in any case, have to live. At Merthyr, the town itself appears sad and off-putting. The streets have not been swept or cleaned; the muck and rubbish pile up in them; black dust, from coal smoke, is spread over the building fronts and even on the faces and clothes of the people. In such a place, indifference and negligence, then destitution soon gain a foothold, which perhaps explains the sorry spectacle that a portion of the working class of Merthyr showed us too frequently.

The Cyfarthfa factory, around which Welsh destitution displayed itself to us for the first time, is one of the biggest iron factories in Wales and thus in all of England. It is second only to Dowlais in Merthyr Tydvil. The latter has seventeen blast furnaces to process iron ore and transform it into cast iron, nearly one hundred and sixty furnaces with reflectors for transforming cast-iron into malleable iron, and a proportional number of rolling mills and power hammers to finish the metallurgical processing of the iron.

The significance of Cyfarthfa is less than that of Dowlais. The factory only has seven furnaces, eighty-four puddler ovens, and only employs six or seven thousand workers; but it is nevertheless a fine plot.

From all these huge factories, the metal that enters in the state of mineral ore, comes out as moulded iron, but most importantly in the form of commercial iron, everything from bars or rods, round or square, sheets, strips, ribbons, to rails. The factories never stop, day or night. The blast furnaces, giants of metallurgical fireboxes, fifteen metres tall, can produce up to forty thousand kilograms of cast iron per twenty-four hours.

"L’Angleterre et la vie anglaise: XXVI. Le sud du Pays de Galles et l’industrie du fer. Carmarthen, les eisteddfodau et les Iron-Works de Merthyr Tydfil", c. 1850s

Alphonse Esquiros (1812 – 1876)

Comme il continuait de pleuvoir, et qu’il n’y avait pas moyen ce jour-là de visiter les forges, je pris le parti de faire un voyage à ma fenêtre. L’endroit était bien choisi. Je ne dirai pas que je fusse au centre de la ville, car il n’y a point de centre; mais l’hôtel occupe dans la grande rue un poste d’observation d’où le regard s’étend sur une vaste place jonchée de décombres et très fréquentée. La population de Merthyr Tydvil jouit, il faut le dire tout de suite, d’une assez mauvaise renommée. La veille, à Cardiff, un employé du chemin de fer m’avait engagé à ne point me rendre pendant la nuit dans ce qu’il appelait une ville dangereuse. Je ne vis rien, absolument rien, qui justifiât ses craintes, se ce n’est qu’il y a là une population pautre et grossière. Les habitans peuvent se diviser en deux classes, ceux qui portent des souliers et ceux qui sont pieds nus. Il m’a été difficile de saisir d’autres distinctions, car presque tous sont revêtus des mêmes habits cousus plus ou moins de mille pièces. Une Anglaise disait qu’il fallait venir à Merthyr Tydvil pour apprendre à raccommoder. Si quelque chose étonne, c’est que de tels vêtemens aient jamais pu être neuf. Ces haillons, vus par un jour de pluie, sous une lumière cendrée, ont je ne sais quoi de fantastique et de navrant. Les enfans demi-nus barbottent dans la boue avec l’indifférence de jeunes canards. Les femmes, habillées en grande partie comme les hommes, couvertes de vestes ou de casaques brunes, chaussées de gros souliers à semelle de bois, arpentent bravement le terrain, portant sur le sommet de la tête une cruche, un baril chargé de charbon de terre ou une lourde corbeille de légumes. Un chapeau à couronne plate, fait en paille grossière, leur permet d’asseoir et d’équilibrer le fardeau. ...

J’étais couché depuis quelques heures déjà lorsque je me sentis réveillé en sursaut par un éclat d’incendie . Je courus à ma fenêtre, vis le ciel rouge comme s’il eût été enflammé par une aurore boréale. J’étais sur le point de crier : au feu! Mais comme personne ne bougeait dans l’hôtel et que tout était tranquille dans le voisinage, je me rassurai, et bientôt je me souvins que je vivais cette nuit-là dans le pays des foreges. La lueur sanglante qui empourprait les ténèbres était en effet une réverbération des ironworks.

As it was still raining, and that there would be no way of visiting the ironworks that day, I decided to make a journey to my window. It was a well-chosen spot. I would not say that I was in the town centre, as there is no centre; but the [Castle] hotel occupies an observation post in the main street from which one can see right across a vast square littered with rubbish and very busy. The population of Merthyr Tydfil has, let there be no delay in saying so, quite a bad name. The previous evening, at Cardiff, a railway worker had told me not to arrive at night in what he called a dangerous town. I saw nothing, absolutely nothing that would justify his fears, apart from the fact that there is here a poor and vulgar population. The inhabitants can be divided into two classes, those who wear shoes and those who go barefoot. I found it difficult to note any other differences, as they were nearly all dressed in the same clothes stitched together from some thousand pieces. An Englishwoman said that Merthyr Tydvil was the place to go to learn how to mend clothes. If there is anything astonishing it is the idea that such clothes had ever been new. These rags, seen on a rainy day, in the ashen light, have something of the fantastical and the distressing. The children paddle half naked in the mud, as indifferent as young ducks. The women, dressed mostly like the men, covered up in brown jackets or over-blouses, with thick wooden-soled shoes, walk confidently to and fro, carrying jugs or basketfuls of coal or even heavy baskets of vegetables on their heads. A hat with a flat crown, made of rough straw, allows them to steady and balance the load. ...

I had already been in bed a few hours when a flash of fire woke me with a start. I ran to my window, saw the sky all red as though ablaze by an aurora borealis. I was about the cry out: fire! But as nobody was moving in the [Castle] hotel and that all seemed calm nearby, I reassured myself and remembered that I was living in the land of forges that night. The blood-coloured light that reddened the darkness was in fact a reflection of the ironworks.