Penrhyn Castle - Overview

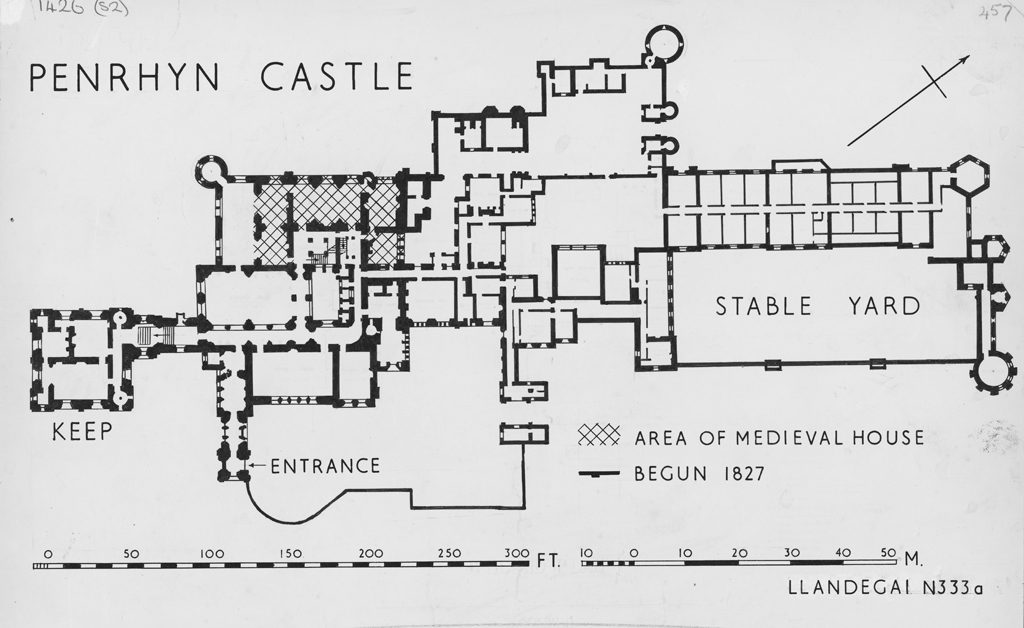

The original manor house on this site dated to the early fifteenth century, a royal license granted in 1438 giving Sir Gwilym Gruffydd permission to crenellate the house and extend the building by adding a fortified tower. Described in a fifteenth century poem by Rhys Goch Eryri, this was a substantial property which was also recorded in drawings made by architect Samuel Wyatt before it was heavily replaced and modified with his designs for a Gothick mansion for the Penrhyn family in 1782. This scheme of work appears to have retained the basement vault, stair tower and great hall from the medieval plan, as well as mirroring the medieval style of the original building.

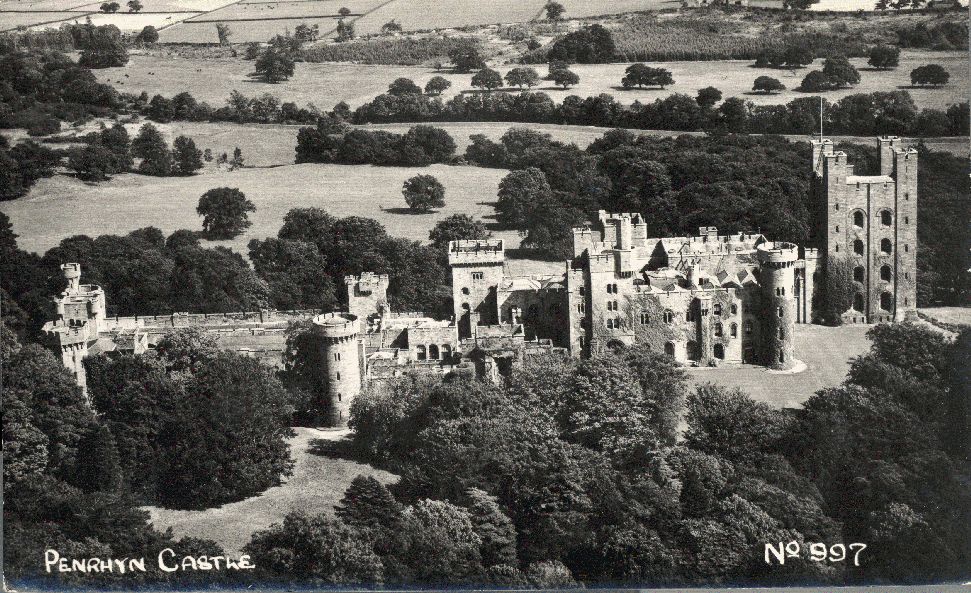

The present building was created by the architect Thomas Hopper between the years 1822 and 1837 for George Hay-Dawkins Pennant who had inherited the Penrhyn estate from his cousin, Richard Pennant. Pennant himself had married into the Penrhyn family and had subsequently made his fortune through slate quarrying industries in north Wales and slavery in Jamaica.

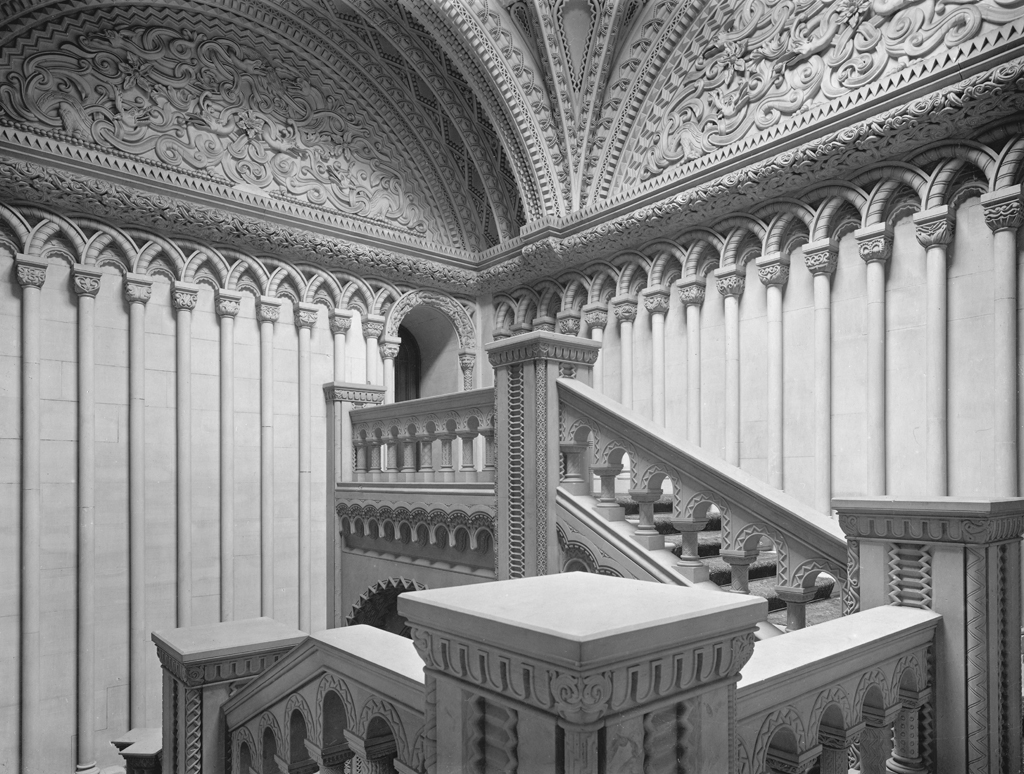

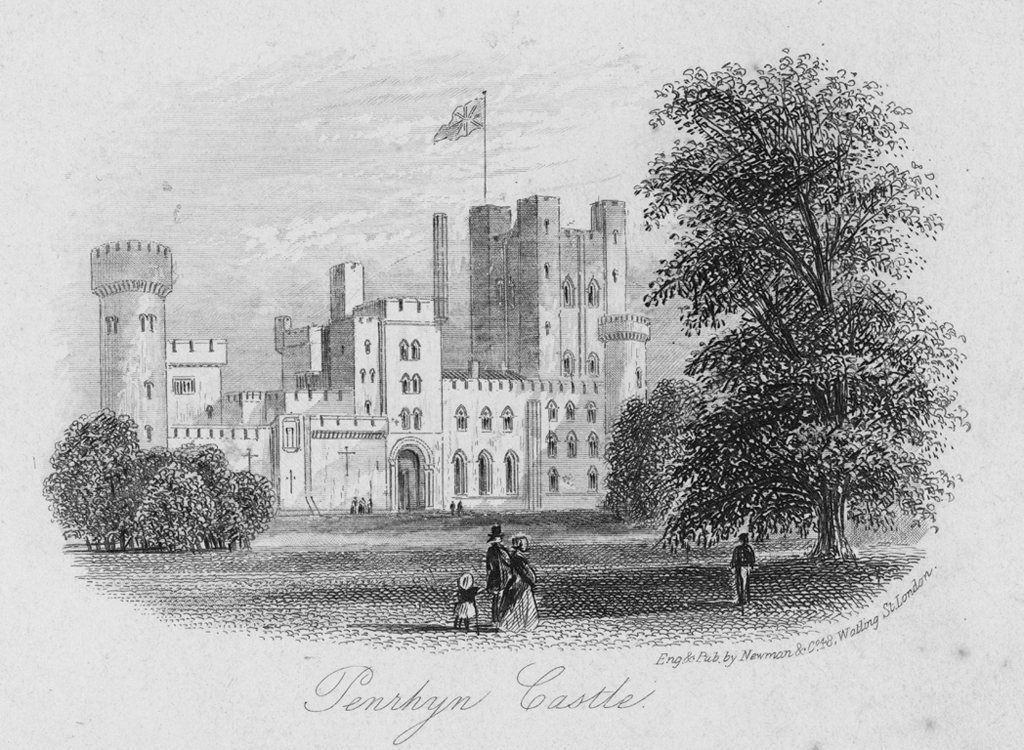

Unlike other architects of mock castles of the Romantic and early Victorian period, Hopper decided against the fashionable Gothic design and opted for a neo-Norman approach instead. His vision of a Norman style went beyond pure architecture, extending to the elaborate, decorative plasterwork employed throughout the library, great hall and staircases as well as the furniture. Unfortunately, George Hay-Dawkins Pennant lived for only three years after the completion of fifteen years of construction work at the castle.

In 1859, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stayed the castle during one of their rare visits to Wales. The queen, however, refused to sleep in the large bespoke slate bed that the Penrhyn family had specifically commissioned for this occasion as it reminded her of a tomb. It was also during this time that the estate began to open its gates routinely to groups of paying tourists who were led through the stately rooms and large planned gardens by the housekeeper.

The last member of the Penrhyn family to live in the castle was Hugh Napier Douglas-Pennant, who died in 1949. The castle and gardens passed into ownership of the Treasury in 1951 and today belong to the National Trust. In addition to the surviving fine interior fittings and furniture, it houses one of the greatest art collections in Wales.

Accounts of Travel

Cartons aus der Reisemappe eines deutschen Touristen, 1836

Karl von Hailbronner (1788 – 1864)

Und dieser ganz reiche Boden, diese unermeßlichen Kupfer-, Schiefer- und Marmorminen gehören einem Manne, der es verdient, Besitzer eines der schönsten Punkte der Welt zu seyn. Dieser Mann heißt Pentland, ein schlichter Privatmann, der über eine Rente von 150.000 Pfd. verfügt. Vor vierzehn Jahren kaufte er von der nun ausgestorbenen Familie gleichen Namens das Pennrhyncastle, eine Ruine aus dem sechsten Jahrhundert, welche auf einer schönen Anhöhe über Bangor liegt. Auf dem Grund dieser berühmten Ruine führte er nun binnen dieser Zeit ein Schloß auf, das dem frühern hier gestandenen möglichst treu nachgebildet ist, und das in seiner äußern und innern Erscheinung vollkommen den Geist des ältesten Ritterthums athmet.

Es besteht aus drei Abtheilungen, die mit Mauern und Thürmen umgeben sind, und erhebt sich hoch und staunenerregend in edler Einfachheit über Meer und Felsen. Es ist ganz aus dem schönen rohen schwarzen Marmor gebaut, der an der Mennaibrücke gebrochen wird, und dieß dunkle Colorit gibt dem weit über den Hügel sich ausbreitenden herrlichen hohen Schlosse mit seinen schönen Thürmen und Zinnen ein ungemein romantisches Aussehen. Die Nachahmung der alten Bauart ist so genau, daß man es auf den ersten Blick für ein altes Gebäude ansehen muß. Allein diese Täuschung wird im Innern bis ins Unglaubliche getrieben, und die Millionen, die hier verschwendet wurden, sind von dem feinsten Geschmack, der sichersten Kenntniß der gothischen Bauart und dem geläutertsten Verstande geleitet worden.

Alle Meubles sind im mittelalterlichen Geschmack, aber möglichst veredelt. Die Wände sind durchgehends mit Damasttapeten belegt, die Meubelüberzüge von Atlas und Sammet, und gleich den dicken Fußteppichen, welche die schönen Mosaikparkets dieser Riesenhallen bedecken, mit antiken Zeichnungen durchwebt. Alle Kamine sind von edlen Marmoren, die Spiegel von kolossalster Größe, die Decken Stucco, gehauener Stein oder Holzschnitt – alles treffliche Arbeit. Die enormen Bettstellen sind alle aus Eichenholz oder Schiefer. Die Meubles sind durchgehends von Eben- oder Eichenholz, und mit außerordentlicher Eleganz und Mannichfaltigkeit gearbeitet. Die Candelaber, welche 12 Schuh hoch sind, bestehen aus reich vergoldeter Bronze. In den Verzierungen aller vereinigt sich der höchste Geschmack mit nabobischer Verschwendung. Das schöne Stiegenhaus ist gleich dem ganzen Gebäude in edlem altsächsischen Style gebaut, und empfängt seine Beleuchtung durch eine Kuppel von mattem Glase. Die antiken Bronzelampen hängen in langen Ketten. Die unendliche Säulenarchitektur scheint doch nicht überladen, da sie im Geiste des Ganzen angebracht ist. Die Bibliothek ist ganz von geschnitztem polirtem Eichenholz, und besteht aus einer großen Halle, die in der Mitte durch freie Bögen getrennt ist. Die Aufstellung der Bücher ist hinter feinen filigranartigen Bronzegittern. Die Krone des Ganzen ist die große Entré im Empfangssaale, die auf hundert schlanken Säulen ein erstaunlich hoch und kühn gesprengtes Dach trägt, und ganz mit weißem Marmor belegt ist. Die Verzierungen sind auch hier vom edelsten Geschmack geleitet, und von Meisterhand ausgeführt. Raum für hundert Gäste und fünfzig Pferde drückt diesem Feenschlosse den Stempel der Großartigkeit und Gastfreundschaft auf, und der König von England wäre glücklich, wenn er einen ähnlichen Palast besäße. Ich habe eine solche durchgeführte Nachahmung der mittelalterlichen Bau- und Lebenssitte bis jetzt für unmöglich gehalten, besonders, wenn sie sich mit dem Comfort des üppigsten Lebens unserer Tage paaren soll. Die Capelle ist in gebührender Einfachheit ganz aus Eichenholz gezimmert, nur die Sitze der Familie sind von gepreßtem Leder mit Gold bedeckt. Marquetterie-Arbeiten, indische Tapeten und chinesische eingelegte Basreliefkästen von Speckstein und Perlenmutter finden sich in mehreren Cabinetten.

Das Schloß selbst ist von dichten hohen Bäumen, die sich aus der Tiefe an ihm emporranken, umgeben, und der Park, der sich bis ans Meer hinab und über die Höhen hinauf erstreckt, verspricht einer der schönsten in England zu werden, wie überhaupt eine ähnliche Schöpfung kaum in einem andern Lande der Welt zu finden seyn dürfte.

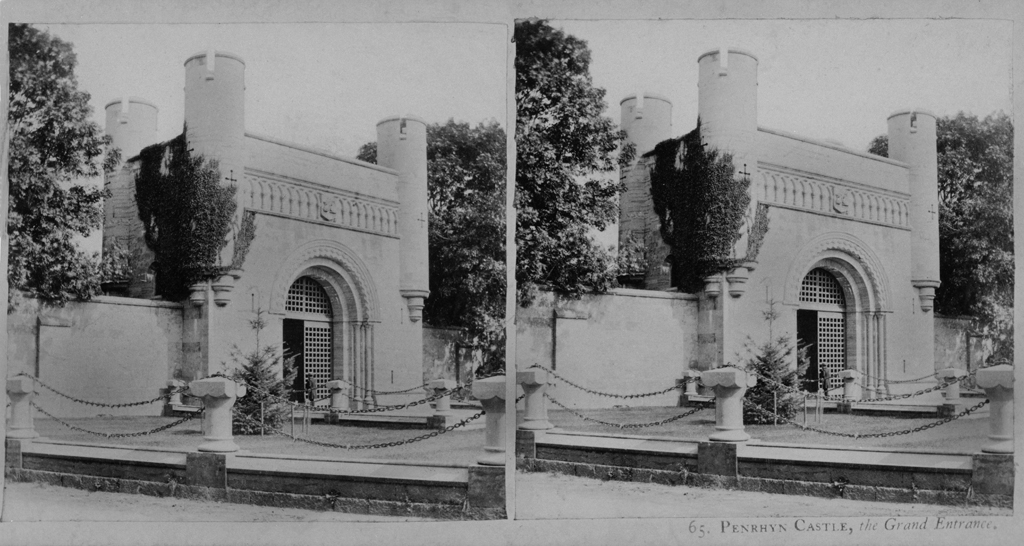

And this very rich soil, these boundless copper, slate and marble mines belong to a man who is worthy owner of one of the most beautiful spots on earth. This man, a simple privateer named Pentland, disposes of £150,000 in annuity. Fourteen years ago, he bought Penrhyn Castle, a sixth-century ruin situated on a beautiful hill above Bangor, from the now extinct family of the same name. On the foundations of this famous ruin he has erected in the intervening years a castle which deliberately resembles its precursor most closely and whose interior and exterior design are infused with the ancient chivalric spirit.

Consisting of three sections surrounded by walls and turrets, the tall, magnificent castle towers in noble simplicity above rocks and sea. It is entirely made of the beautiful rough black marble broken near the Menai Suspension Bridge; and this dark colouration lends the glorious high castle a truly romantic aspect, as it sprawls out across the hill with its handsome turrets and battlements. The imitation of the old design is so very precise that on first glance it looks a truly ancient pile. This illusion is then carried to incredulous perfection inside, and the millions squandered here betray the finest taste, the most assured expertise in Gothic architecture and a most sober mind. All furniture is of a medieval, but refined taste. The walls are covered throughout with damask wallpaper; the sateen and velvet furniture coverings have antique drawings woven into them, similar to the lush carpets that cover the beautiful mosaic parquet of these giant halls. All firesides are of precious marble, the mirrors of colossal size, the ceilings covered in stucco, carved stone or wood – everything is splendid work. The enormous beds are all made of oak or slate.

The furniture is entirely of ebony or oak and worked in extraordinary elegance and variety. The 12-foot tall candelabras are of gilded bronze. All ornamentations betray the marriage between the most sophisticated taste with nabob squander. Like the rest of the building, the fine staircase is constructed after the Old-Saxon style and is lit through a frosted glass cupola. Long chains suspend the antique bronze lamps from the ceiling. The endless pillar architecture does not appear excessive as it has been created entirely within the spirit of the whole. The library is entirely of polished carved oak and consists of a large hall divided in its centre by free arches; the books are presented behind filigree-like bronze lattices. The jewel in the crown is the grand reception hall which is entirely clad in white marble and carries on hundred slender pillars an astonishingly lofty and audacious sprung roof. Here too, the ornaments show the most noble taste and were fashioned by an expert hand. This fairy castle carries the seal of magnificence and hospitality as it offers space to one hundred guests and fifty horses and the King of England would count himself lucky if he owned a palace like it. Until now, I had thought such a perfect imitation of medieval design and life-style impossible, especially when it is expected to meld with the comforts of most luxuriant life in our days. With appropriate simplicity, the chapel is timbered with oak and only the seats for the family are covered with pressed leather and gold. Marquetry works, Indian wallpapers and small Chinese inlaid bas-relief chests of soap stone and mother of pearl are assembled in various cabinets.

The castle itself is surrounded by dense, tall trees that snake up on it from the deep. Extending from the sea up to the heights, the park promises to become one of England’s finest as it will be nigh impossible to find a similar creation in any other country of the world.

Briefe eines Verstorbenen, 1828

Hermann von Pückler-Muskau (1785 – 1871)

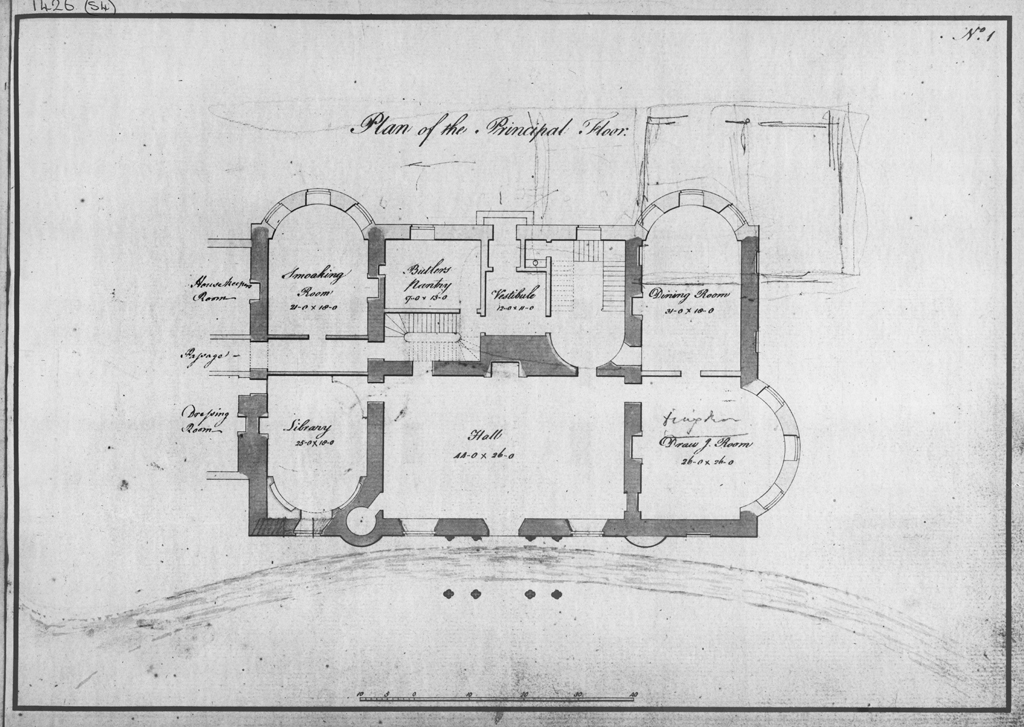

Dieses merkwürdige Gebäude ist von einem in jeder Hinsicht steinreichen Manne aufgeführt; denn seine, eine Stunde weiter im Gebürge liegenden Steinbrüche, bringen ihm jährlich 40.000 L. St. Er hat an einer der vortheilhaftesten Stellen, am Ufer des Meeres, einen weitläuftigen Park angelegt, und die sonderbare, aber meisterhaft ausgeführte, Idee gehabt, alle Gebäude darin in dem altsächsischen Style zu erbauen. Man schreibt diese Architektur fälschlich in England den Angelsachsen zu, da sie doch von den sächsischen deutschen Kaisern herrührt, und gewiß keines dieser vielfachen Monumente älter ist. Schon die den Park umgebende, wohl eine deutsche Meile fortlaufende hohe Mauer, erhält dadurch ein seltsames Ansehen, daß in ihrer obern Schicht 3 bis 4 Fuß hohe, aufrecht stehende, unegale, spitzige Schieferstücke eingemauert sind, eine zugleich sehr zweckmäßige Werrichtung. Bei jedem Eingang droht ein thurmartiges Fort mit Fallgittern u. s. w. dem Eindringenden, (kein übles Symbol für die Illiberalität der modernen Engländer, die ihre Garten und Besitzthümer strenger, als wir unsere Wohnstuben, verschließen) dann muß der Besucher noch eine Zugbrücke passiren, ehe er den dunklen Thorweg der imponirenden Burg betritt. Der schwarze, nur roh bearbeitete, Marmor von der Insel Anglesea, aus dem die großen Massen bestehen, harmonirt wunderbar mit dem majestätischen Charakter der Gegend. Bis in die kleinsten Details, selbst die Stuben der Bedienten, und noch geringere Plätze nicht ausgenommen, ist mit genauer Sorgfalt alles reiner old Saxon style. Im Eß-saal fand ich eine Nachahmung des Dir früher beschriebenen Schlosses Wilhelms des Eroberers zu Rochester. Was damals nur ein großer Monarch ausführen konnte, realisirt jetzt als Spielwerk, nur noch größer, schöner und kostbarer, ein simpler Landgentleman, dessen Vater vielleicht mit Käsehandel anfing. So ändern sich die Zeiten! Der Grundplan des Gebäudes, den mir der gefällige Architekt vorlegte, gab Gelegenheit zu einigen häuslichen Informationen, die ich Dir hier mittheile, weil fast alle englische größere Landhäuser so eingerichtet find, und sie, wie so vieles, die Zweckmäßigkeit englischer Gebäude darthun. Die Dienerschaft hält sich nie im Vorzimmer, hier die Halle genannt, auf, welche immer wie die Ouverture bei einer Oper, den Charakter des Ganzen anzudeuten sucht. Sie ist gewöhnlich mit Gemälden oder Statuen geschmückt, und dient, wie die elegante Treppe und alle übrigen Zimmer, nur zum beliebigen Aufenthalte der Familie und Gäste, welche sich lieber manchmal selbst bedienen, als immer einen solchen dienenden Geist hinter ihren Fußstapfen wissen wollen. Die Bedienten sind daher alle in einer entfernteren großen Stube (gewöhnlich im rez de chaussée) versammelt, wo sie auch zusammen, ohne Ausnahme, männliche und weibliche, zu gleicher Zeit essen, und wo alle Klingeln aus dem Hause ebenfalls aboutiren. Diese hängen in einer Reihe nummerirt an der Wand, so daß man sogleich sehen kann, von woher geklingelt wird; an jeder ist noch eine Art Pendulum angebracht, der sich 10 Minuten lang, nachdem die Klingel schweigt, noch fortbewegt, um den Saumseligen an seine Pflicht zu erinnern! Das weibliche Personal hat gleichfalls ein großes Versammlungszimmer, worin es, wenn nichts anderes vorkömmt, näht, strickt und spinnt. Daneben befindet sich ein Behältniß zum reinigen der Glaswaaren und des Porzellains, welches den Mädchen obliegt. Jede von diesen, so wie die männlichen Diener, haben im obersten Stock ihre besondere Schlafzelle. Nur die Ausgeberin (housekeeper) und der Haushofmeister (butler) bewohnen unten ein eignes Quartier. Unmittelbar an das der Ausgeberin anstoßend ist die Kaffeeküche und die Vorrathskammer für Alles, was zum Frühstück nöthig ist, welche, in England wichtige, Mahlzeit speciell zu ihrem Departement gehört. Auf der andern Seite ist ihr Waschetablissement, mit einem kleinen Hofe verbunden; es besteht aus 3 Piecen, die erste zum Waschen, die zweite zum Plätten, die dritte bedeutend hohe, welche mit Dampf geheizt wird, zum Trocknen bei schlechtem Wetter. Neben des Haushofmeisters Logis befindet sich seine pantry, ein geräumiges feuerfestes Zimmer mit rund umher laufenden Schränken, wo das Silber aufbewahrt wird, das er auch hier putzt, so wie die zur Tafel nöthigen Glas- und Porzellainwaaren, die ihm, sobald sie von den Mädchen rein gemacht sind, welches alles sehr pünktlich geschieht, sogleich wieder abgeliefert werden müssen. Aus der pantry führt eine verschlossene Treppe in die Bier- und Weinkeller, welche der butler ebenfalls unter sich hat.

This remarkable edifice was built by the proprietor of the slate quarries, situated about three miles distant, which bring him a yearly income of 40,000l. He has laid out a park in the most delightful situation on the sea-shore; and has pursued the strange but admirably executed idea of erecting every building within its enclosure in the old Saxon style of architecture. The English falsely ascribe the introduction of this style to the Anglo-Saxons: it arose in the time of the emperors of the Saxon line ; and it is quite certain that none of the numerous Saxon remains are to be traced to an earlier date. The high wall, which surrounds the park in a circuit of at least a German mile, has a very singular appearance; pointed masses of slate three or four feet high, and of irregular shape, are built upright into the top of the wall. At every entrance a fortress-like gate with a portcullis frowns on the intruder, – no inapt symbol, by-the-bye, of the illiberality of the present race of Englishmen, who shut their parks and gardens more closely than we do our sitting-rooms. The favoured visitor must then cross a drawbridge before he passes the gate-way of the imposing castle. The black marble of the island of Anglesea, rudely hewn, harmonizes admirably with the majestic character of the surrounding scenery. The pure Saxon style is preserved in the minutest details, even in the servants’ rooms and meanest parts of the building. In the eating-hall I found an imitation of the castle of William the Conqueror, at Rochester, which I formerly described to you. What could then be accomplished only by a mighty monarch, is now executed, as a plaything, – only with increased size, magnificence and expense, – by a simple country-gentleman, whose father very likely sold cheeses. So do times change!

The ground-plan of the building, which the architect had the politeness to show me, gave occasion to certain domestic details, which I am glad to be able to communicate to you; because nearly all large English country-houses are constructed on the same plan; and because in this, as in many other things, the nice perception of the useful and commodious, the exquisite adaptation of means to ends, which distinguish the English, are conspicuous. The servants never wait in the ante-room, – here called the hall, – which, like the overture of an opera, is designed to express the character of the whole: it is generally decorated with statues or pictures, and, like the elegant staircase and the various apartments, is appropriated to the use of the family and guests, who have the good taste rather to wait on themselves than to have an attendant spirit always at their heels. The servants live in a large room in a remote part of the house, generally on the ground-floor, where all, male and female, eat together, and where the bells of the whole house are placed. They are suspended in a row on the wall, numbered so that it is immediately seen in what room any one has rung: a sort of pendulum is attached to each, which continues to vibrate for ten minutes after the sound has ceased to remind the sluggish of their duty. The females of the establishment have also a large common room, in which, when they have nothing else to do, they sew, knit, and spin: close to this is a closet for washing the glass and china which comes within their province. Each of them, as well as of the men-servants, has her separate bed-chamber in the highest story. Only the ‘housekeeper’ and the ‘butler’ have distinct apartments below. Immediately adjoining that of the housekeeper, is a room where coffee is made, and the store-room containing every thing requisite for breakfast, which important meal, in England, belongs especially to her department. On the other side of the building is the washing establishment, with a small court-yard attached; it consists of three rooms, the first for washing, the second for ironing, the third, which is considerably loftier, and heated by steam, for drying the linen in bad weather. Near the butler’s room is his pantry, a spacious fire-proof room, with closets on every side for the reception of the plate which he cleans here; and the glass and china used at dinner, which must be delivered back into his custody as soon as it is washed by the women. All these arrangements are executed with the greatest punctuality. A locked staircase leads from the pantry into the beer and wine cellar, which is likewise under the butler’s jurisdiction.

(Tour in England, Ireland, and France, in the Years 1828 & 1829. With Remarks on the Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants, and Anecdotes of Distinguished Public Characters. In a Series of Letters. By a German Prince. Ed. B –. Vol. 1. London: Effingham Wilson, 1832)

Ein Herbst in Wales, 1856

Julius Rodenberg (1831 – 1914)

Hier nun gerieth ich zuerst in jenen Touristenschwarm, dem ich sobald nicht wieder entrinnen sollte. Der ganze Schloßhof stand voll Menschen, – Damen mit ledernen Handschuhen, die Fechthandschuhen nicht unähnlich waren, und blauseidenem Wetterdach vor dem Strohhut; Herren in carrierten Mützen und den Hals in steife Collars geknebelt – denn ganz bequem kann sich’s der Gentleman sogar auf der Reise nicht machen. Die Schaulust dieser ungeheuren Schaar wurde sectionenweise befriedigt; alle Viertelstunde öffnete sich das Thor, um zwei Dutzend heraus- und andere zwei Dutzend hineinzulassen. Mittlerweile hatte ich Muße, das Thürwappen zu studiren. Es war ein Hirschbock, der von einer Geißel getrieben ward – mit der Umschrift: aequo animo. Das berühmte Dante’sche: „Lasciate speranza!" paßte nicht beßer für den Besucher der Hölle, als der Pennant’sche Schildspruch für den Besucher dieser Burg. Wahrlich – es gehörte viel Gleichmuth dazu, sich mit 24 Gentlemen von einer vertrockneten, finstern, mistrauischen Schloßverwalterin durch ein Schloß hetzen zu lassen, das in seiner exquisiten Pracht vom wärmsten Lebensgenuß zeugte und dazu anregte. Ich kam mir recht vor, wie jener Hirschbock, der von einer Geißel getrieben wird, und dachte dabei immer „aequo animo!" Mit den 24 Gentlemen, von welchen einer einen schreienden Sprößling auf den Armen trug, hatte sie freilich leichtes Spiel; sie liefen – der Gentleman mit dem Schreihals immer voraus – so schnell durch alle Säle, Hallen und Gemächer, daß die Geißel kaum folgen konnte. Ich aber bereitete ihr vielen Ärger. Hier blieb ich vor einem Caneletti und Pierro del Vayn, dort – in der Schloßcapelle – vor einem Glasfenster stehen; überall hatte ich mir etwas in’s Notizbuch zu schreiben, Nichts war vor mir sicher. Das verdroß sie sehr. Ich gieng immer meine eignen Wege und verirrte mich sogar einmal so, daß ich die Gesellschaft nur durch’s Gehör fand, indem ich mich nämlich dem Gentleman mit dem Schreihals nachfühlte. Kurz und gut – vom Ärger gieng die Geißel zum Verdacht über; und da ich so gar nichts an mir hatte, was Gentleman-Iike war, vielmehr einen Knotenstock führte und den Hemdkragen breit über dem lose flatternden Halstuch trug, so hielt sie mich für einen heimlichen Dieb, für einen verkappten Räuber. Sie wich nicht mehr von meiner Seite, sie sah mir auf die Hände, sie murmelte unverständliche Reden. Was hätte ich Dir entwenden sollen, Beste? Etwa eine von den goldbordirten Bettdecken? Unter dem steifen Brokat würde ich doch nicht schlafen können! Oder eins von diesen vergoldeten Waschbecken? Einen mit Sammet ausgeschlagenen Rollsessel? Oder gar einen dieser Marmorkamine? Einmal allerdings, als ich in dem Bibliotheksaal, wo die herrlichsten Bande hinter vergoldeten Gittern in Reih und Glied zu Tausenden aufgestellt sind – als ich da auf einem der Mahagonitische aufgeschlagen die Firmin Didot’sche Bilderausgabe des Horaz sah, da allerdings wandelte mich eine gar seltsame Lust an, da zuckte allerdings meine Hand – aber ich las das „Integer vitae!“. . . „Wer reinen Herzens lebt“ . . . und obendrein stand die Geißel mit ihrem furchtbarsten Blicke neben mir... und der Firmin Didot’sche Bilderhoraz und die Unschuld meiner Seele waren gerettet!

On a hillock above this hamlet, which is quite charming in the rarest degree, lies Penrhyn Castle, the seat of the previously mentioned Pennants who count among the richest landowners in this part of north Wales. Admittedly, it is a new building, but with its turrets and battlements, its irregularity of lines, its narrow windows, its dark ground colour and the dense ivy cover, even at close range, it gives the impression of a grand Old-Saxon castle. Massive walls and a fast, high gate surround the park. Upon entering, one is welcomed immediately by all the freshness and all the fragrances of the forest. How very different from a French park is such an English one with all its natural beauty! Here there are no fountains with sphynx figurines, no Apollo and no Venus, no trimmed yew hedges and orangeries – but there are oaks hundreds of years old, whispering beeches and gleaming birches; one can see twelve-pointers burst through the fir thicket or roe prancing across the luscious meadow – indeed, one may even follow them, if one so fancies. – Everything is nature, fresh, succulent nature! Finally, the castle steps into view from the surrounding thicket; the grey walls, the weathered design of its turrets and the jagged battlements glimmer sweetly through the foliage. The castle courtyard offers the most glorious prospect of the deep below. The castle with its tall windows and flagged turret lies behind, while the fir and bramble-covered hill stretches out in front, and in the distance lie the soft, sunny green lawn, the forest with its strong beeches and the clear blue sea, garlanded on its right by an embankment in bloom and the shining rock of Penmaenmawr that falls straight into the sea. The background is a hazy, delicate blue against which the Great Orme’s Head steps into view like a pale drawing.

Here now I was drawn into the swarm of tourists from which I was then unable to escape for some time. The entire courtyard was filled with people, – ladies with leather gloves not very dissimilar to fencing gloves and blue silken parasols in front of their straw hats; gentlemen with plaid caps and their throats suffocated by stiff collars – because no gentleman on tour should be entirely comfortable. The curiosity of this enormous crowd was satisfied one section at a time; every quarter of an hour, the gate opened to dismiss one dozen visitors and welcome another two dozen. In the meantime, I indulged my muse and inspected the coat of arms on the door. It depicted a stag being chased with a whip and carried the inscription, ‘aequo animo’. Dante’s ‘Lasciate speranza!’ could not have been a more perfect fit for a visitor of Hell than Pennant’s motto for the visitor of this castle. Truly – it demanded a lot of equanimity to join the twenty-four gentlemen and be guided by a shrivelled, lowering, suspicious housekeeper around a castle projecting exquisite grandeur and encouraging the warmest enjoyment of life. I rather felt like said stag chased with the whip and was constantly reminded of the ‘aequo animo’! She had an easy time with the twenty-four gentlemen, one of whom was carrying his screaming offspring in his arms; they proceeded – the gentleman with the screaming toddler in front – so quickly through every saloon, hall and chamber that the whip had trouble keeping up with them. But I cause her much aggravation. First I dawdled in front of a Canaletti and Pierro del Vayn, then – and in the castle chapel – in front of a stained glass window; everywhere I had to stop and scribble something into my notebook; nothing was safe from me. This made her quite cross. I always ventured on my own paths and even got lost at one time so that I was only able to find the group again by following my ears, sounding out the gentlemen with the screaming child. To make a long story short – the whip progressed from annoyance to suspicion. And since nothing about me was gentleman-like, with my knobbly cane and my broad shirt collar folded over a floppy bandana, she took me for a cunning thief, for a burglar in disguise. She no longer parted from my side, watched my hands and muttered inaudibly. What was I supposed to pilfer, dear? One of the gold-braided duvets? I couldn’t possibly sleep beneath the stiff brocade! Or one of these golden sinks? One of the velveteen armchairs on rollers? Or maybe even one of the marble fireplaces? Once, however, in the library – where thousands and thousands of the most splendid volumes are lined up in file behind gilt lattices – as I spotted Firmin Didot’s illustrated edition of Horace, a strange urge overcame me and indeed my hand twitched – but I read the ‘Integer vitae!’ . . . ‘Whoso lives with purity of heart’ . . . and on top of it all, the whip stood beside me with the grimmest look on her face . . . and Firmin Didot’s illustrated Horace and my soul’s innocence were saved!